February 01, 2023

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been grinding on for nearly a year (or nearly a decade if you ask the Ukrainians). In this time, momentum has swung back and forth between Russia and Ukraine. But now, the front lines have stabilized, making gains harder to come by for both sides.

There’s consensus that in the near term, Moscow will be unlikely to achieve its war aims and Kyiv will be equally unlikely to liberate all its territory. A lasting ceasefire, let alone a negotiated settlement, remains as distant as ever because neither country is willing to make territorial concessions as long as they believe they can achieve a stronger negotiating position through continued fighting. And both sides still believe defeat is unthinkable and victory is at least possible (if not likely).

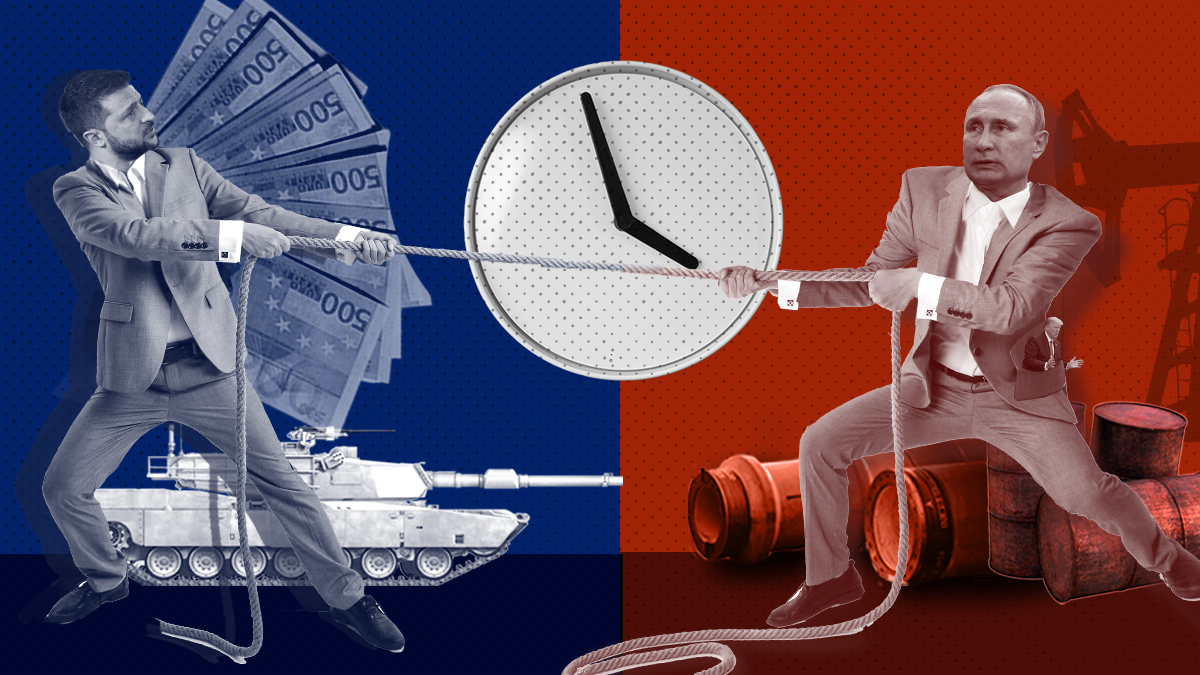

There’s no end in sight to what seems to be evolving into a war of attrition. Which raises the critical question: Who has the advantage in a drawn-out war, Russia or Ukraine?

Let’s look at both sides of the argument.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily for free and get your daily fix of global politics on top of my weekly email.

Time is on Ukraine’s side

Ukraine can continue to defend itself and retake territory for as long as the United States and Europe keep the guns and dollars flowing. Despite suffering massive losses, Ukraine currently has better offensive and defensive capabilities than it did on Feb. 24, 2022. Ukrainians’ will to fight is intact, and their forces are better armed, better trained, and better led than their Russian counterparts. Ukraine’s successful counteroffensives last summer and fall put Russia on the defensive; advanced Western weaponry (including armored vehicles and air-defense systems) will help Ukraine make further inroads into Russian-held territory and put Kyiv in a better negotiating position.

Western support for Ukraine isn’t crumbling. Despite the costs of support and the side effects of the war, public opinion in the West remains steadfast in backing military and financial aid for Kyiv. In the US, only a minority of the Republican caucus opposes it. In Europe, support has held even in countries with new populist governments like Italy. Meanwhile, Germany is decoupling from Russian gas remarkably quickly and will survive the winter just fine – a sign that Russia’s biggest source of leverage over European countries is effectively over.

Russia’s military will continue to underperform Ukraine’s. Moscow lost some of its best men and equipment in the first months of the invasion; it’s now running short of important military capabilities, and its ability to replenish them is constrained by decades of underinvestment, corruption, and now sanctions. Much of the equipment it has left in storage is of low quality or in poor condition, and conscripts lack the motivation and training of professional and volunteer soldiers. The manpower and matériel Russia can throw at the war going forward are decidedly inferior to what it fielded last Feb. 24.

Mounting economic woes will erode Russia’s ability and willingness to fight. Russia’s economy shrunk by 3.5% in 2022 and it’ll do so by a similar or greater amount this year. While high oil prices have thus far cushioned the blow felt by most Russians, the impact of sanctions will grow significantly over time. Some of the toughest measures — export controls, the oil embargo, the price cap on Russian crude — are only now starting to take effect. The long-run erosion of living standards and productive capacity due to Russia’s decoupling from advanced industrial economies will be acute and permanent. This will make it hard for Russia to reconstitute its defense industrial base, blunting its war effort. Most importantly, combined with mounting casualties, it will reduce popular and elite support for the war and put pressure on Putin to de-escalate.

Time is on Russia’s side

Ukraine needs ever-more-powerful Western weapons to sustain the fight, but Western support will dry up sooner rather than later. Ukraine’s military capabilities are almost entirely dependent on continued support from the West and especially from the United States. But Western publics will get weary of the war as the costs mount and the risk of World War III becomes more apparent. With Republicans in control of the House, a growing GOP bloc opposed to aid for Ukraine, and a Republican president potentially taking office in 2025, Washington’s commitment to Kyiv can only weaken. The moment US support withers, so will Europe’s… and Kyiv’s ability to defend itself.

Even with continued Western support, Russia can win on the battlefield. Russian troops are no longer on the back foot. Now that they’ve had time to fortify their defensive positions and fill their ranks with better-trained conscripts, Ukraine won’t be able to repeat the kinds of successful offensives it achieved last year. While Kyiv may have overperformed in the early days of the war, a drawn-out conflict favors the more powerful belligerent. Both sides have taken severe losses, but Russia is a larger country with much more manpower, equipment, and military-industrial capacity it can throw at the war. Western weapons notwithstanding, Ukraine is likely to run out of men long before Russia does.

Unlike Ukraine and the West, Russia has the staying power to survive a protracted conflict. The West has used up most of the leverage it had against Russia, yet sanctions haven’t succeeded in crippling Russia’s economy or military. Moscow continues to have strong commercial or security ties with China, Iran, India, and many developing countries, and it maintains the ability to produce weapons domestically without imported components. Most ordinary Russians haven’t seen their living standards decline, and they continue to buy into the Kremlin’s pro-war propaganda. But even if that were to change, Putin’s ability to crush dissent means domestic political stability isn’t under threat; he can afford to continue piling pressure on Ukraine and the West at minimal risk to his rule.

Why it matters ...

Because the answer determines the pace and volume of Western aid to Ukraine.

When Kyiv launched a successful counteroffensive that won back swaths of Russian-occupied territory last summer and fall, Ukraine’s backers believed that the longer the fighting went on, the more likely Ukraine would emerge victorious. Accordingly, they carefully calibrated their support for Kyiv to avoid provoking the Russians unnecessarily. Now that the Russians have gotten their act together a bit, many have come to believe time is on Moscow’s side. This explains why the West finally agreed to deliver tanks in the hopes of achieving a quicker end to the conflict (or at least ensuring the Ukrainians could continue to effectively defend themselves).

Trouble is, Ukraine definitely can’t win without steadily incremental support from the West, but the level and path of Western support both depends on and determines Western leaders’ beliefs about the trajectory of the war. As calls for fighter jets come into play, this isn’t getting any easier.

Readers, tell me what you think.

🔔 Don't forget to subscribe to GZERO Daily and get the world's best global politics newsletter every day PLUS a weekly special edition from yours truly. Did I mention it's free?From Your Site Articles

- War in Europe is top priority at Munich Security Conference - GZERO Media ›

- Is there a path ahead for peace in Ukraine? - GZERO Media ›

- Ukraine dominates the dialogue in Munich - GZERO Media ›

- Ukraine dominates the dialogue in Munich - GZERO Media ›

- Mongolia: the democracy between Russia and China - GZERO Media ›

- Biden’s visit to Ukraine signals US commitment, but war gets tougher - GZERO Media ›

- Xi plays peace broker - GZERO Media ›

- Christie: US should keep leading Ukraine aid - GZERO Media ›

- Russia's war: no end in sight - GZERO Media ›

- Ian Bremmer: Why Rogue Russia was predicted as Eurasia Group's 2023's top risk - GZERO Media ›

More For You

Prime Minister Narendra Modi waves to the crowd during the opening ceremony at AI Impact Summit 2026 at Bharat Mandapam, in New Delhi on Thursday. Switzerland President Guy Parmelin also present.

DPR PMO/ANI Photo

“For India, AI stands for all inclusive,” reads the billboard outside this week’s AI Impact Summit in New Delhi organized by the Indian government, the first major gathering on the subject in the Global South.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema reacts during the announcement of provisional results of the 2025 Gabonese presidential election by the Ministry of the Interior, at the headquaters of the Rassemblement des Batisseurs (RdB), in Libreville, Gabon, April 13, 2025.

REUTERS/Luc Gnago

2.5 million: The population of Gabon who can no longer get onto certain social media platforms, like YouTube and TikTok, after the government suspended access on Tuesday.

- YouTube

In this episode of "ask ian," Ian Bremmer breaks down two high-stakes negotiations in Geneva: Russia-Ukraine and indirect US-Iran talks, calling both “underwhelming” with little progress.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.