On Wednesday, Indonesians will head to the polls to elect their next president. Around 192 million people are eligible to vote in the world's third largest democracy. We asked Straits Times Jakarta bureau chief Francis Chan for the lowdown on what it all means.

Here's what you need to know:

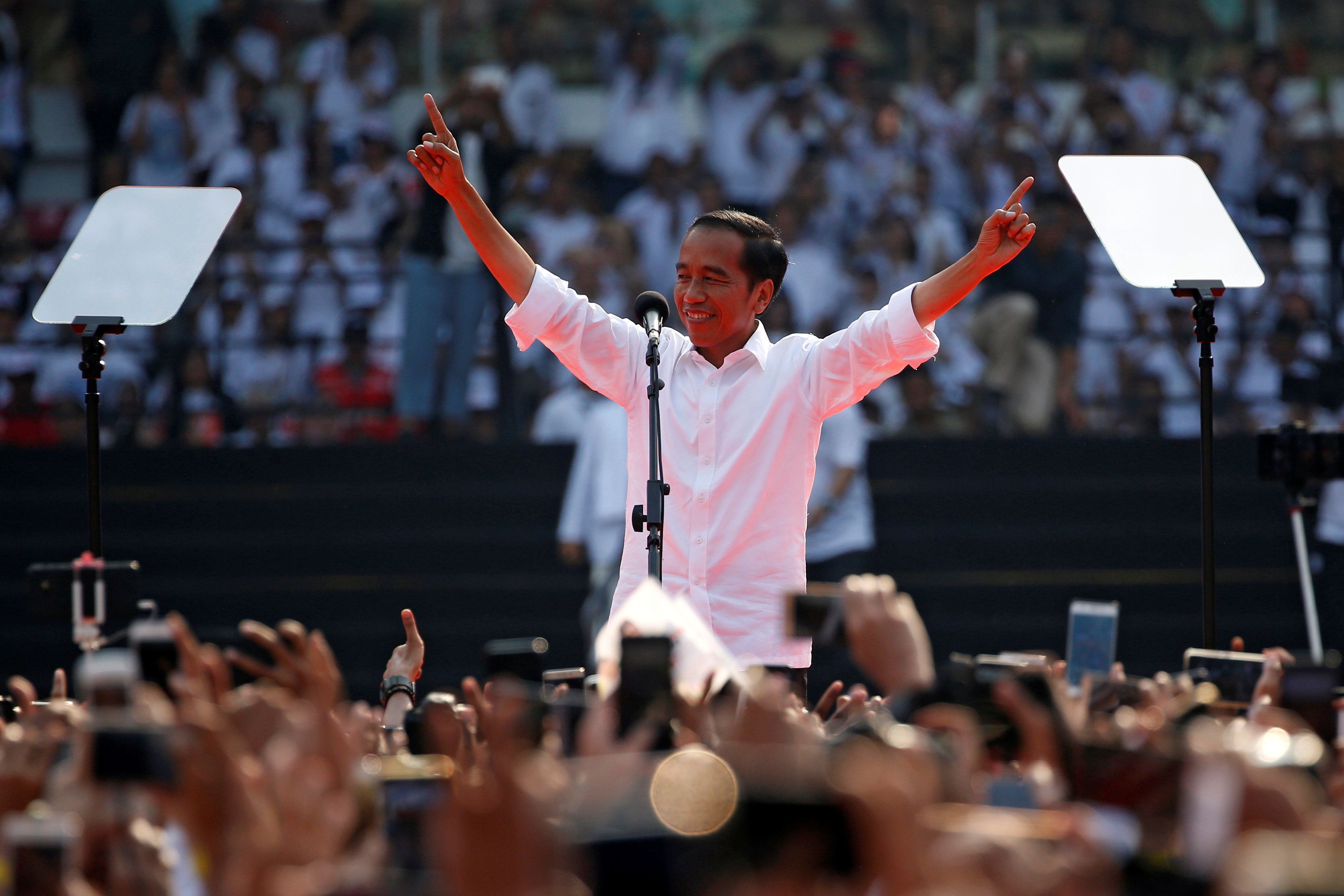

1. Who is Joko Widodo?

Joko Widodo ("Jokowi') has been president of Indonesia since 2014. He's a carpenter who went from furniture businessman to president in 10 years, and on Wednesday he'll seek reelection to a second 5-year term.

2. What has he accomplished as president and what has he failed to accomplish?

Indonesia is now better-connected because of Jokowi's ambitious infrastructure push. He's delivered on several welfare programs for the people.

But while the country recorded a steady 5 percent growth annually since he was elected, that fell short of his 7 percent campaign promise.

More was also expected of him in tackling corruption, poverty and human rights abuses.

3. For readers outside Asia who know little about Indonesia's domestic politics, tell us why this election is important?

It's the world's third-largest democracy (behind the US and India) and has the largest Muslim population in the world. Each time Indonesia holds an election, it's a chance for the country to prove that Islam and multiparty democracy are compatible—or that they're not.

4. What are the most important issues in this election?

A rising cost of living, opportunities for young people, and religion. Youth unemployment has topped 19 percent in recent years, compared to 5 percent for the population as a whole.

There's a growing divide between conservative Muslims who'd like to see religion play a more prominent role in national political life and moderate Muslims and Christians.

5. How do politicians build a national reputation in a country of 260 million people spread across more than 17,000 islands that includes more than 300 ethnic groups speaking more than 700 regional languages?

Social media plays a big role, especially given Indonesia's high Internet penetration rates and Indonesians' active use of social media platforms.

6. There's a perception that Islamic fundamentalism has become a more potent force in Indonesian politics. Is this true, and how is it changing the political landscape?

Muslims make up 90 percent of Indonesia's 260 million people, so religious fervor will naturally be a part of any political contest. But these elections come amid rising religious polarization across the country, ignited just before the fall of Jakarta's Chinese-Christian governor in 2017.

7. Why has "fake news" become such an important problem in Indonesia?

Fake news is a problem everywhere, but probably more so in Indonesia because social media has emerged as an important campaigning tool. Social media is made even more important by the fact that Indonesia is such a geographically dispersed country, spanning over 3,700 miles from East to West.

*This interview was conducted with Straits Times Jakarta bureau chief Francis Chan. The answers were edited and condensed for clarity.