May 24, 2021

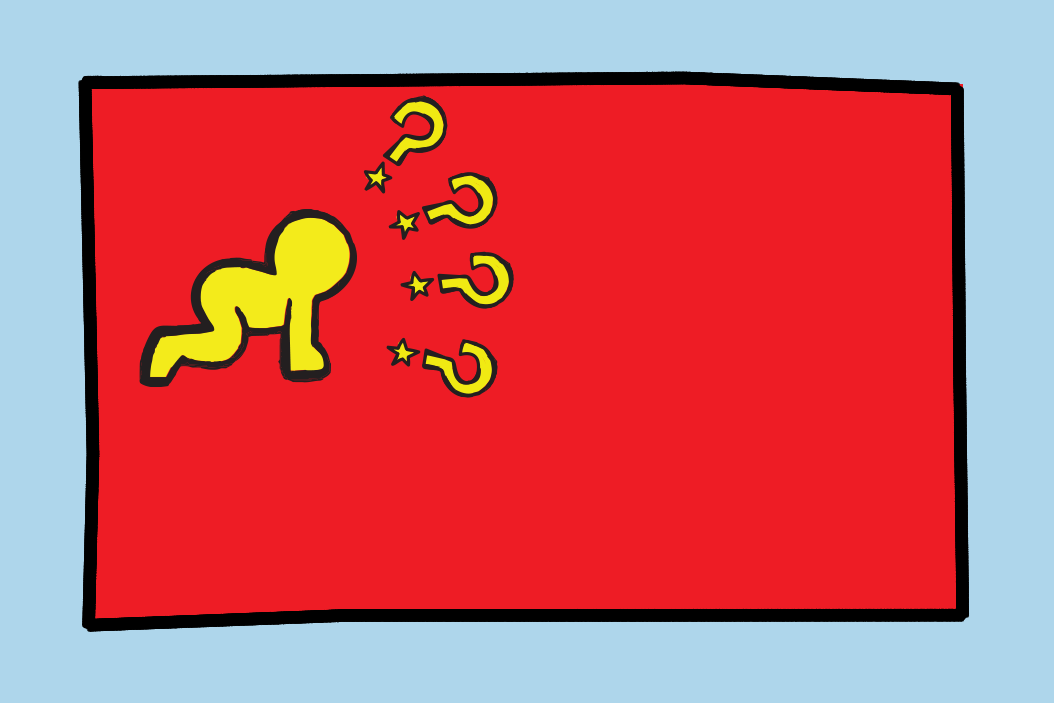

The world's most populous country has a big new problem: not enough babies. New census data show that at some point later this decade, the number of people living in China will start to fall.

How will that affect China's bid to overtake the US as the world's largest economy? Are there political implications for President Xi Jinping? China's leaders have so far been slow to come to grips with the magnitude of the looming demographic threat. GZERO talked with China experts at Eurasia Group to discuss the challenges ahead.

What did the latest census data show?

Childbirths plummeted by 18% in 2020, and although that was partially the result of the pandemic, it was also the fourth consecutive year of declining births. The country's fertility rate, which measures births per 1,000 women of childbearing age, remained very low at 1.3, technically above the 1.2 level from the last census in 2010, but most experts believe the earlier figures were substantially undercounted. The country's fertility rate is now one of the lowest among the world's major countries. It is also well below the 2.1 level at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next.

Other data showed that the country's working-age population (defined as those between 15 and 59) has fallen by 40 million people since 2010, and represents 63.4% of the population, down from 70.3% percent a decade ago. Meanwhile, the number of people aged 65 and above has swollen from 8.9% to 13.5% of the total population. It is expected to rise to 20% by 2025.

All this taken together, it looks as though China's population is in danger of starting to shrink soon. No one knows precisely when, but a study late last year said it could be as soon as 2027.

How did China get to this point?

The problem is rooted in the strict family planning policies that China introduced in the 1970s, which became known as the "one child policy." At the time, the country's leaders were worried that a booming population could stretch the country's resources and derail their development goals, so they limited all families to having just one child. People born before then are now hitting retirement, and there are fewer people in the younger generation to replace them.

In 2015, after decades of rapid economic growth, the government raised the cap to two children. That prompted a spike in childbirths for two years, but the effect has been wearing off because of the high cost of raising children in today's China. Housing has grown increasingly expensive in the nation's largest cities, and families are under intense social pressure to spend lavishly on their children's education to help them get ahead in life.

What are the economic implications of a shrinking population?

For decades one of China's great economic advantages was its huge and rapidly urbanizing population, which meant a massive supply of cheap labor to make and build things it can sell around the world. If that pool of labor gets smaller, that hits at the heart of the economic model that made China the second largest economy in the world. What's more, a decline in the number of domestic consumers — especially working-age consumers — would put a crimp on officials' plans to promote more spending at home to reduce the country's reliance on exports.

Meanwhile, the rapid increase in the numbers of retirees, who are living longer thanks to improvements in healthcare, will require more government spending on pensions, exacerbating the problems many local authorities are already facing with fast-rising debt loads.

Don't birth rates tend to decline in most societies as they become more prosperous?

Yes, but in China's case the phenomenon is occurring at an earlier stage of its development than in other Asian countries such as South Korea and Japan. That means Chinese citizens have less wealth to draw on in their old age and the state has built less of a safety net.

Can technology and automation pick up some of the slack?

In theory, yes. Automation provides a way out for firms dealing with rising labor costs. And while the number of new workers may be declining in China, rising education levels are translating into higher productivity per worker, which boosts economic output. But investments in technology take careful planning and may take years to yield benefits. They also threaten to create more economic and social disruptions in areas that are not well-equipped to embrace them, such as China's traditional rust belt in the northeast, which is already reeling from high unemployment, rising welfare costs, and slowing growth.

What does all this mean for Chinese efforts to project influence on the global stage?

A shrinking population does not in itself jeopardize China's geopolitical objectives. However, the burden on the economy and fiscal system may constrain the ability of the government to make investments in areas important to expanding the country's influence, including promoting clean technologies at home, building up the military, and lending to other countries.

Are officials capable of addressing these issues?

They see the challenge, but their responses so far have been incremental and scattered. Restrictive family planning policies — such as the two-child limit — remain in place, and there is no comprehensive plan to incentivize childbirths, which will require changes in education and housing policy. One reason for the dithering is that, as with all governments, Beijing has been focusing on more immediate issues, such as the pandemic and the trade war with the US. Another reason is that facing up to demographic challenges threatens sensitive political narratives in China, which focus on a bright future and improving livelihoods for the population.

In the run-up to the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party in July, there isn't the political will to confront these looming problems head on. But policy debates are heating up, especially in the wake of the latest census data, and we will be hearing much more about this issue in the months and years ahead.From Your Site Articles

- The future of the Chinese Communist Party - GZERO Media ›

- Why is Xi Jinping willing to slow down China’s economy? - GZERO Media ›

- Why is Xi Jinping willing to slow down China’s economy? ›

- Why is Xi Jinping lurking in bedrooms? - GZERO Media ›

- China’s discontent & the Russia distraction - GZERO Media ›

- China's year of unpredictability - GZERO Media ›

- Scott Galloway on population decline and the secret sauce of US success - GZERO Media ›

- The global population is aging. Is the world prepared? - GZERO Media ›

- Should we be worried about population decline? - GZERO Media ›

More For You

Bad Bunny during the Super Bowl LX halftime show press conference at Moscone Center.

Kirby Lee-Imagn Images

100 million: The number of people expected to watch the Super Bowl halftime performance with Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican superstar and newly minted Album of the Year winner at the Grammys.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

- YouTube

An imminent US airstrike on iran is not only possible, it's probable.

Americans are moving less — and renting more. Cooling migration and rising vacancy rates, especially across the Sunbelt, have flattened rent growth and given renters new leverage. For many lower-income households, that relief is beginning to show up in discretionary spending. Explore what's changing in US housing by subscribing to Bank of America Institute.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.