June 02, 2021

Morocco and Spain have spent the past two weeks at loggerheads over Madrid allowing the leader of the independence movement for Western Sahara, a former Spanish territory claimed by Morocco, to get medical treatment for COVID in a Spanish hospital. Polisario Front chief Brahim Ghali has now left the country, but the Moroccans are still furious.

Indeed, Rabat's initial response was to open its border gates to allow a deluge of thousands of migrants to overwhelm the Spanish border in Ceuta, a Spanish enclave on the Moroccan coast. Although that crisis ended in a matter of days, the wider issue that caused it in the first place remains unresolved.

Why does Morocco care so much about this sparsely populated desert territory, and why is it now pushing so hard to gain full control of Western Sahara?

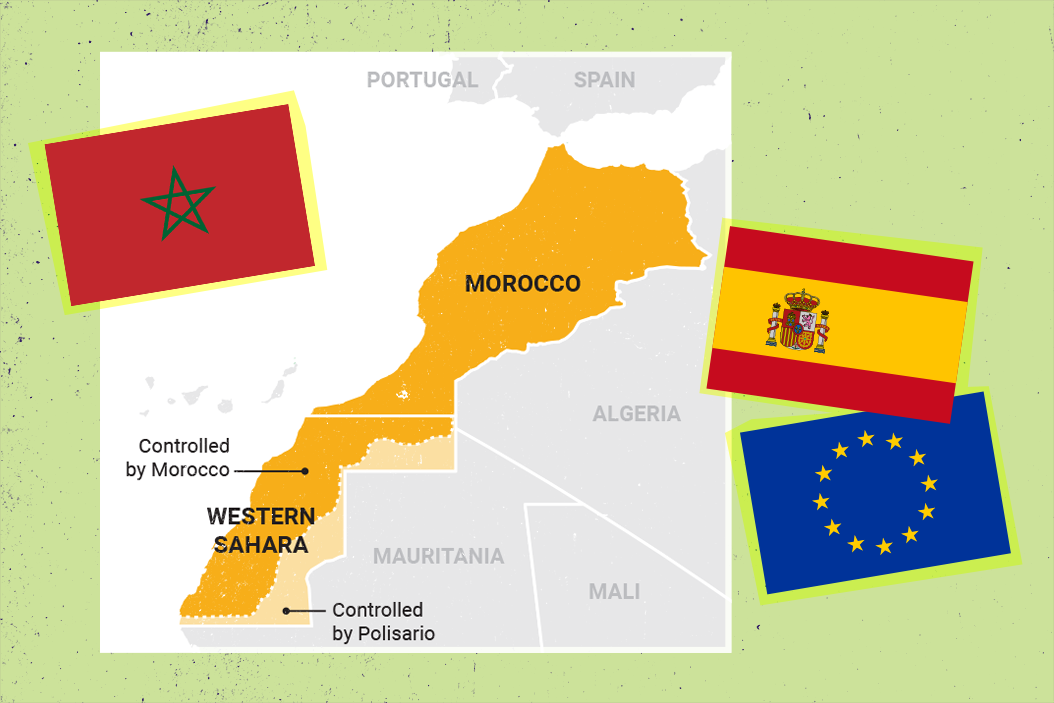

First, a bit of history. Western Sahara, long populated by nomadic tribes, was administered by Spain from 1884 until 1975. Morocco and the native Sahrawis, represented by the Polisario Front, later fought a bloody war that ended in a 1991 UN-backed ceasefire agreement which called for an independence referendum that Rabat has largely ignored. Since then, Western Sahara has been in limbo — Morocco now controls 80 percent of the territory, including the coastline, and the Sahrawis control a thin strip bordering Algeria and Mauritania.

But that small chunk of land is immensely important for the Moroccans because it's the main route for overland trade with the rest of Africa via Mauritania. Morocco's much longer border with regional rival Algeria, which backs the Polisario Front and hosts thousands of Sahrawi refugees, has been closed for almost 30 years.

Morocco also needs Western Sahara's minerals, mainly its phosphate rock riches. Including the disputed territory's estimated deposits — which the Moroccans are already mining in the areas they control — Morocco accounts for three-quarters of the world's reserves of this scarce mineral, used to make synthetic fertilizer for agriculture.

And then there's fish. A lot of fish. So much that Morocco is eager to share it with EU fishing vessels, for lucrative fees. But a wide-ranging trade agreement between Morocco and the European Union has been held up since 2018 because of a dispute over access to waters off Western Sahara. Moreover, if there's fish, perhaps there are also untapped offshore oil and gas.

Thank you, Donald Trump. During the last weeks of the Trump administration, the US became the first UN member state to recognize Morocco's claim over Western Sahara, reportedly in exchange for normalizing ties with Israel. Recognition by the world's most powerful nation was a huge win for Rabat, which now feels emboldened to test how hard it can push other countries to do the same, particularly Spain and the broader EU. And Morocco now seems to have the upper hand, as Turkey often does when it successfully weaponizes migrants to get what it wants from the Europeans.

The problem for Spain and the EU is that they need Morocco more than Morocco needs them. For Spain, Moroccan cooperation is crucial to stemming the flow of African migrants to its borders. The EU, for its part, is deeply concerned about those migrants using Spain as a springboard to enter other EU countries. Brussels also wants to sign a trade deal with Rabat that includes Western Saharan fisheries to offset fishing rights lost to Brexit.

Morocco is presumably happy to help protect the Spanish border, and let EU vessels fish in their waters, and get hard cash in return. But the money is not enough anymore. For Rabat, full sovereignty over Western Sahara is as much of an existential issue as illegal immigration is to Madrid and Brussels.

Looking ahead. Spain's current leftwing government can't afford another migrant crisis that'll give more ammunition to the anti-immigration, far-right Vox party. And the EU has learned its lesson from dealing with Turkey on refugees. Morocco's leverage over both means that Sahrawis' pursuit of self-determination is all but assured to take a backseat for the Europeans.From Your Site Articles

More For You

How is the US is reshaping global power dynamics, using tariffs and unilateral action to challenge the international order it once led? Michael Froman joins Ian Bremmer on GZERO World to discuss.

Most Popular

- YouTube

In this Quick Take from Munich, Ian Bremmer examines the state of the transatlantic alliance as the 62nd Munich Security Conference concludes.

- YouTube

At the 2026 Munich Security Conference, Brad Smith announces the launch of the Trusted Tech Alliance, a coalition of global technology leaders, including Microsoft, committing to secure cross-border tech flows, ethical governance, and stronger data protections.

When the US shift from defending the postwar rules-based order to challenging it, what kind of global system emerges? CFR President Michael Froman joins Ian Bremmer on the GZERO World Podcast to discuss the global order under Trump's second term.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.