Joyful skeptics of prevailing wisdom will recall a scene from the classic 1973 Woody Allen movie “Sleeper.”

A doctor tells a colleague that Allen’s character, who has awoken in the 22nd century after a 200-year nap, has requested a breakfast of wheat germ, organic honey, and tiger’s milk. The second doctor is puzzled. “You mean he didn’t ask for steak, cream pies, or hot fudge?”

No, says the first doctor. “Back then those things were believed to be unhealthy, precisely the opposite of what we now know to be true.”

What we now know to be true.

As a society, we believe all kinds of seemingly scientific things that later turn out to be wrong. We sometimes funnel our biases and beliefs into science that sounds “right.” And we are confident that whatever we know is the cutting edge of knowledge – after all, we can’t know any more than we know.

There was, for example, a time when cocaine was considered a normal part of soda. When lead-based paint was thought to be perfectly fine for the baby’s room. When doctors endorsed cigarettes!

These beliefs affected the lives of untold millions of people. And they were, at the time, backed by the available science.

But one science-backed belief that used to enjoy the support of a huge swath of America’s elite institutions was especially pernicious. Not only that, it was instrumental in the passage of one of the most sweeping legal changes in American history.

Exactly a hundred years ago this Sunday, Congress approved the 1924 Immigration Act, a deeply prejudiced piece of legislation that effectively ended all immigration from Asia – and severely restricted it from Southern and Eastern Europe – for more than 40 years.

The law, which by the 1960s would halve the immigrant share of the US population to less than 6%, was a reaction to the wave of immigrants that started coming in the 1880s, when economic hardship in southern Italy and extreme antisemitism in the Russian empire pushed millions of Catholics and Jews across the Atlantic in search of a new American life.

By 1924, advocates of harsher limits on immigration – an alliance comprising labor unions worried about wage competition, Progressives who worried about crowded slums, and good old-fashioned Boston Brahmin racists and antisemites – had been working for decades to get the ultra-restrictive bill they wanted.

They fought against corporate lobbies that wanted cheap labor, steamship companies that thrived on immigrant passages, and increasingly well-organized groups of recent arrivals who were gaining power at the ballot box.

What helped to get the 1924 bill over the line, as historian and former New York Times public editor Daniel Okrent tells it in his superb recent book “The Guarded Gate,” was the imprimatur of science – or at least a form of it called “eugenics.”

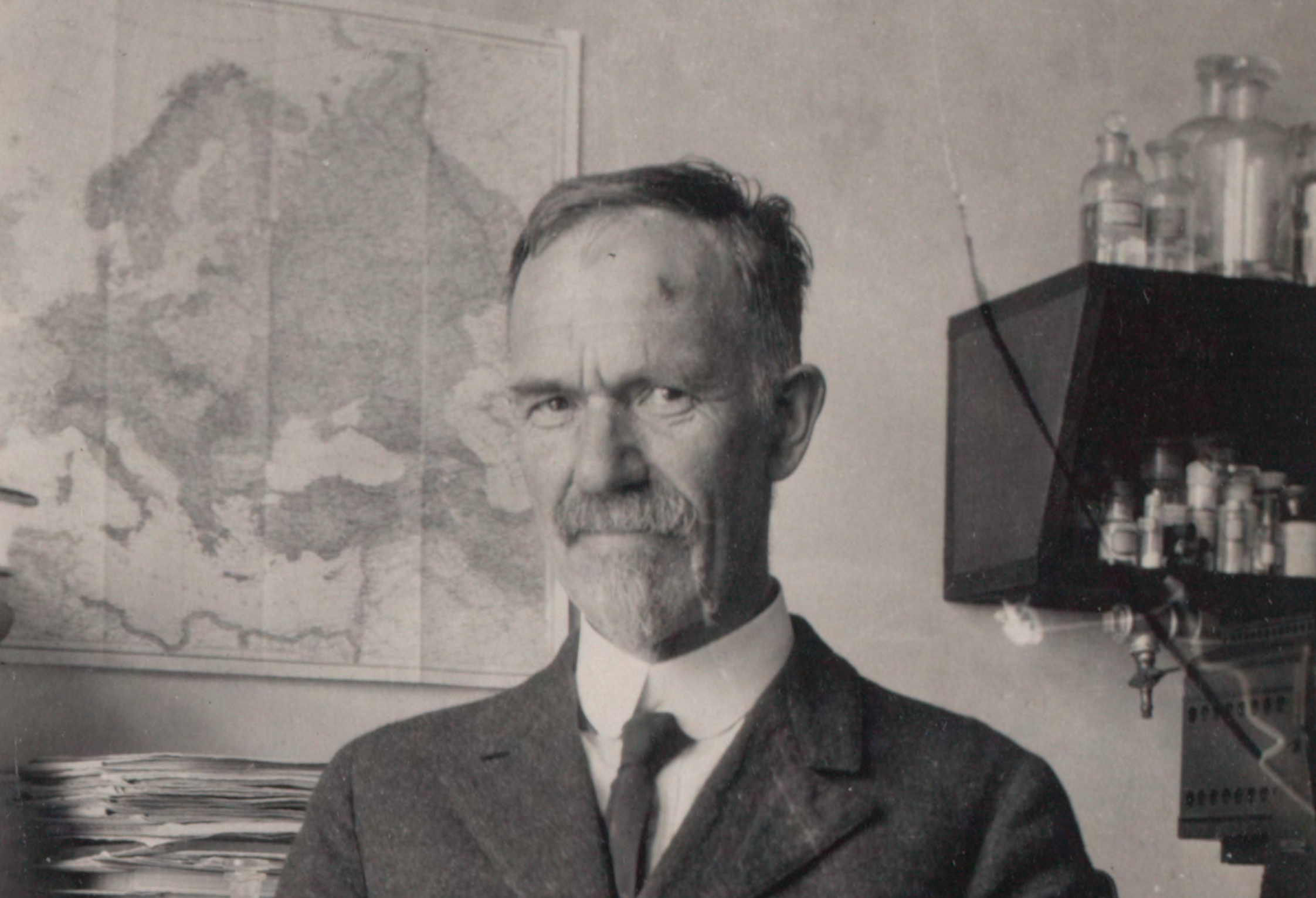

By perversely applying Darwin’s theory of evolution to human personality traits, the eugenicists thought they had proved that intelligence, discipline, and moral virtue were determined by genes, that certain races (that is, whites from Northern and Western Europe) had more of these “positive” traits than others, and that allowing in “inferior races” would destroy America. On this view, Asians, Catholics from Ireland and Italy, and Jews from Eastern Europe were seen not only as culturally incompatible or politically suspect, but as overtly dangerous to the genetic stock of the country.

This wasn’t just fringe stuff. This was no mere Progressive Era QAnon. Eugenics captured the attention – and money – of Very Serious People™ who thought of themselves as reformers, educators, and technocrats. These included university presidents at Columbia, Princeton, and MIT, editorial writers at the Washington Post or The Nation, and the bosses of institutions like the American Museum of Natural History. Teddy Roosevelt himself warned of the perils of “race suicide.”

Now, a century later, it’s again the spring of ‘24. We are again embroiled in a ferocious debate about immigration on the eve of a presidential election. In some ways the debate is very different: The laws are very different now, and the focus is chiefly on the problem of large-scale undocumented migration, a phenomenon that hardly existed a 100 years ago. And eugenics, needless to say, has been discredited.

In some ways, though, the arguments are also the same. Reasonable ones about the impact of immigrants on working-class wages, or the ability (or willingness) of local communities to rapidly absorb large numbers of immigrants. But also vile ones about people from abroad – in our time primarily from South America, West Africa, and Asia rather than Southern and Eastern Europe – “poisoning the bloodstream” of America. Those owe a debt of hate to the eugenicist lexicon of the early 20th century.

At a time when Americans are locked in increasingly zero-sum clashes about a range of other political and cultural issues, and when trust in institutions of all kinds is falling, the power of eugenicists to shape the immigration debate in Congress a century ago – crazy as it seems today – is worth reflecting on.

You and I hold any number of beliefs today – about health, about technology, about people, about politics, or about nature – that will without a doubt look wrong, cruel, or incredibly stupid in 2124.

I would bet – hope! – that few are as wretchedly ugly and destructive as what the eugenicists cooked up. But not all are as harmless as ordering hot fudge for breakfast, either. What do you think they might be? What is the best way to find out?

Let me know what prevailing beliefs today you think will look dumb a century from now, and I’d be happy to include some of the best responses after my column next Friday. Write to us here, and include your name as you’d like it to be published and where you’re writing from. Enjoy.