Living Beyond Borders Articles

December 13, 2020

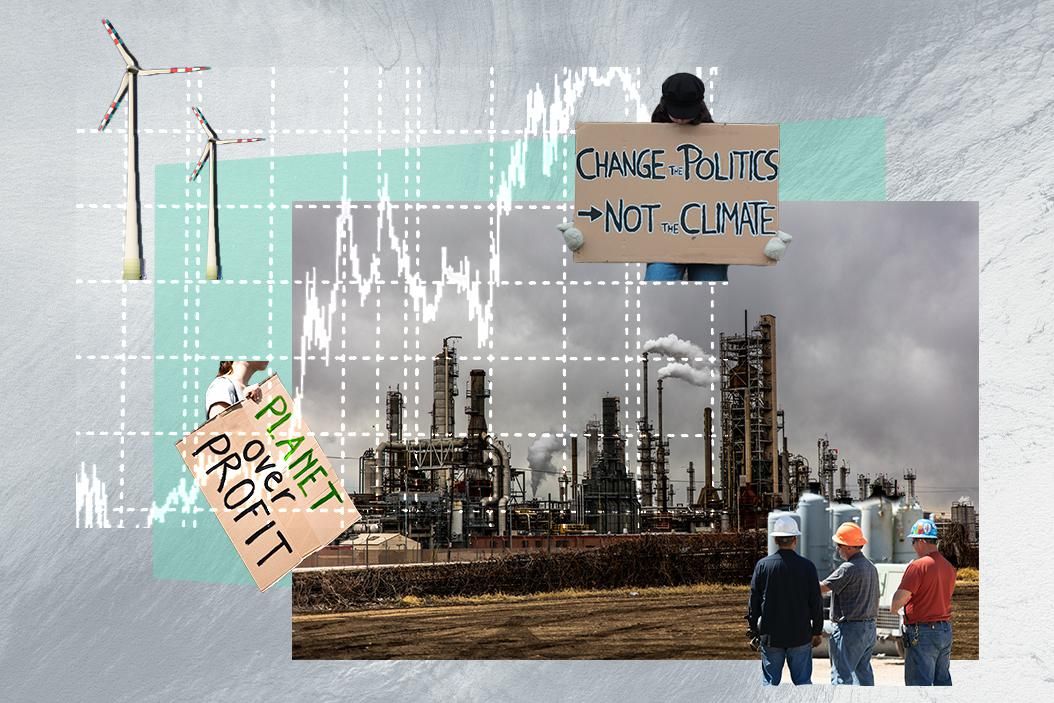

The future of ESG: Global investor interest in supporting sustainable companies has soared in recent years. But how do you define "sustainable"? One widely used criteria is ESG, which stands for "environmental, societal, and (corporate) governance." The catch, however, is that there still isn't a uniform definition of ESG criteria and regulation across different markets. For example, the EU and the US — home to the largest financial markets in the world — still disagree on the basic question of whether pension funds can classify or not. Meanwhile, outside of these two markets and some parts of Asia, the concept of ESG is relatively scarce in much of the developing world. So, what about China, where the sustainable investment market remains virtually untapped? If the Chinese join the party, it could be a game-changer. The larger the ESG market, the more lucrative it can be — and the better that is for society and the planet. But that means that the world's three largest economies, which hardly see eye-to-eye on anything these days, will have to agree on common standards for global ESG investment to truly take off. We're watching to see if and how that might happen.

Renewable China: The world's second largest economy pollutes — a lot. But China has also in recent years emerged as a leader in renewables investment. Why? One reason is that Beijing is increasingly worried about the security of its massive oil imports. Much of those come from the Middle East, where China has relied for decades on the US to provide security. But now that the US itself is a leading oil producer, Washington is less interested in the region, making China more vulnerable to supply disruptions there. At the same time, China's heavy reliance on coal-fired energy plants has poisoned China's air and water, and even stoked unrest. All of this has prompted the Chinese government to become, in recent years, an industry leader in the development of renewables like solar and wind power technologies. China is also the world's largest maker and buyer of electric cars. One big thing to watch here is how much China cooperates with other economies -- particularly the US. Are we headed for a world where the two largest economies are green tech rivals or partners?

Those who see red in a greener world: The sustainability revolution is undoubtedly good for the planet and, as we've seen, for financial investors too. But spare a thought for those who have the most to lose in all of this: oil-exporting economies. Even before the coronavirus pandemic kneecapped global demand for oil — briefly sending prices into negative territory — they faced big challenges. The shale oil revolution in the US had whittled away American demand for foreign crude. Emissions reduction and renewables policies in the US, China, and Europe were undercutting long-term demand for what the Saudi Arabias, Russias, Nigerias, Venezuelas, and Iraqs of the world sell. In these countries, oil delivers more than two thirds of export earnings and is the bedrock of the budget. Over the next decade, oil exporters have tough choices to make about how to diversify their economies. Demographic pressures make the problem especially acute in the Middle East and Africa: in Saudi Arabia and Nigeria, for example, more than two thirds of the population is under 30. Even when oil prices were high, the energy industry wasn't going to provide enough good jobs for them. Countries with bigger rainy day funds, like Saudi Arabia or Russia, may have more time to figure this all out. But what of cash-strapped Iraq or economically-wrecked Venezuela?

More For You

- YouTube

Alina Polyakova, President and CEO of the Center for European Policy Analysis, warns that NATO faces a defining moment.

From the sidelines of the 62nd Munich Security Conference in Munich, Polyakova told GZERO's Tony Maciulis that the Arctic has become “an arena of incredible global competition,” with Russia and China expanding their ambitions. While President Trump’s focus reflects “the right instincts” on security, she argues allies must strike a mutual deal to secure the region together.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

Every year, the Munich Security Conference, the world’s leading forum on international security, releases data that sheds light on how citizens view global risks.

The US government reportedly plans to fund MAGA-aligned groups in Europe. The stated aim is to oppose European laws on online speech.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.