September 09, 2021

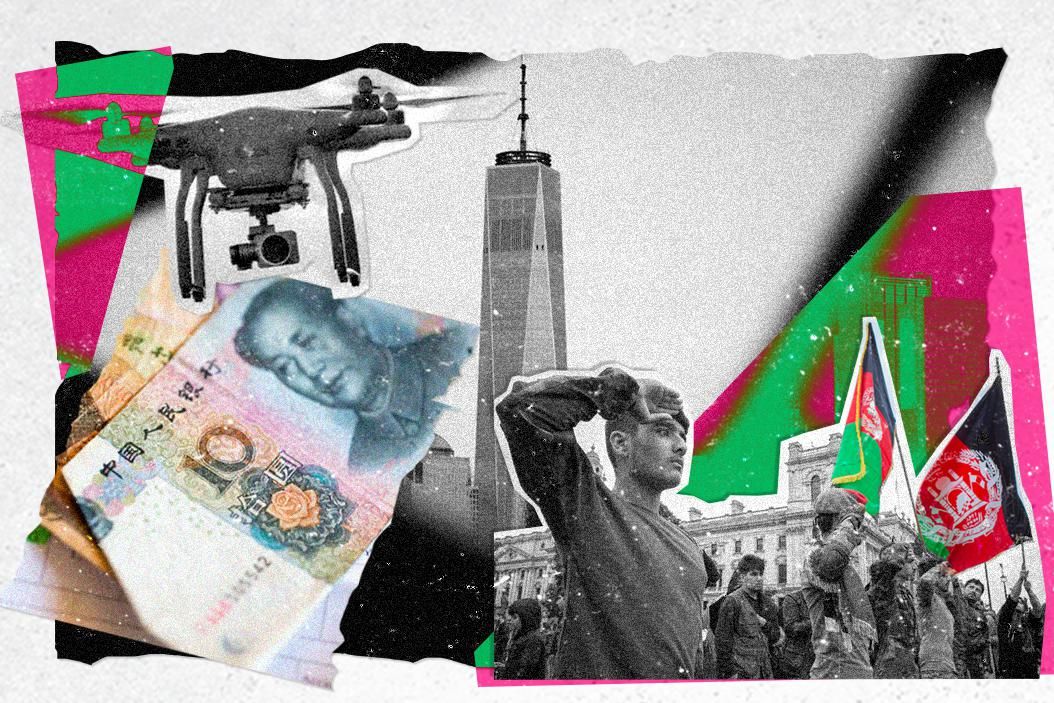

The world has changed dramatically since the terrorist attacks on New York And Washington on September 11, 2001. Pop culture has evolved — significantly — as have the ways we eat, communicate, work, and get our information about the world.

Geopolitically, the past two decades have been transformative, and these developments have impacted how many observers reflect on the post-9/11 era.

Here are three examples of big geopolitical shifts over the past two decades, and how they may influence our understanding of global events today.

China got big. In 2001, China wasn't even a member of the World Trade Organization, and it was still considered a developing country that was largely closed off from the global economy. In 2001, China recorded a GDP per capita of $1,053 compared to $10,500 in 2020.

Today, China's leaders speak of "a new era" in which China will move "closer to center stage" in world affairs. President Xi Jinping now calls for a "Chinese solution" for the world's problems.

In 2001, China's geopolitical interests were not strictly defined in opposition to the US' (and vice versa). In the aftermath of 9/11, the former leader of China's Communist Party, President Jiang Zemin, expressed some sympathy with the US and supported a call for action at the United Nations Security Council. He also backed an anti-terrorism resolution calling for the ousting of the Taliban that had provided safe haven for al-Qaeda.

That spirit of cooperation is a far cry from what we've seen in recent years, when Beijing, a veto-wielding member of the UNSC, has used its power to thwart US-driven resolutions. When it comes to Afghanistan, China says it is open to recognizing the Taliban and is now working against US strategic interests in the region.

The US is no longer willing to be the world's policeman. In September 2001, the United States was at the height of its post-Cold War power. America was the unrivaled global hegemon, and despite arguments over how and whether to intervene in African conflicts and the former Yugoslavia, there was more domestic consensus across the political spectrum about how and when the US should deploy that power, particularly after the 9/11 attacks. Just one member of the US Congress, California Democrat Barbara Lee, voted against the war in Afghanistan.

American politics have always been acrimonious, yet in the immediate post-9/11 era, there was more bipartisan consensus about what the US mission in Afghanistan should be — and less opposition to the idea that America had a broader "responsibility to lead" to advance American political values. That's no longer the case. As Ian Bremmer recently pointed out, if there's anything that Democrats and Republicans agree on today — and there isn't much — it's that the US should withdraw from Afghanistan. Part of the reason for that, Bremmer explains, is that lawmakers — and American voters — no longer want to be "the promoter of common values."

In October 2001, 80 percent of Americans supported a ground invasion in Afghanistan to get the bad guys who wreaked havoc on New York City. Today, by contrast, there is very little appetite to send American troops to far-flung conflict zones while Americans at home grapple with COVID recovery, crime and other domestic political priorities. The recent killing of 13 US service members amid the hasty US withdrawal from Afghanistan is likely to reinforce that stance. That's not to say that the US is pursuing an isolationist foreign policy — far from it. But American assumptions about the role the US should play in the world have certainly changed.

What is a war anyway? Twenty years ago, a military offensive — a boots-on-the-ground intervention — was the primary way for the US to exert maximum pressure on an adversary. But the nature of war and combat has evolved dramatically over the past two decades. State-of-the-art pilotless aircrafts and "killer drones" can be used in surveillance missions and war, and from an army's perspective, can provide a more precise and less costly alternative to traditional aerial missions. Most militaries, including NATO, are looking at how to use technology to avoid casualties without compromising the mission's objectives.

The United States has been developing its drone tech for some time, but in recent years, China too has been increasingly focused on upping its drone game: China's state-run Aviation Industry Corps has sold advanced drone tech to at least 16 countries over the past decade, and is also building a drone factory in Saudi Arabia, the first in the region.

China, for its part, has pushed back on accusations that its drone production is fueling a new arms race, but the Pentagon is certainly on edge because more countries are developing drone technologies that are being used in war-like scenarios, sometimes by bad actors. (Azerbaijan used Turkish-supplied drones against Armenia in last year's conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, while the Kremlin has agreed to send drones to Myanmar's oppressive military junta.)

And future wars are more likely to be fought mainly with cyber-weapons than with air power projected by aircraft carriers. In fact, cyberspace is an increasingly dangerous arena for conflict. That's true not only for war, but for acts of terrorism — including the next 9/11.

From Your Site Articles

- 20 years since 9/11 attacks - GZERO Media ›

- The Graphic Truth: The cost of America's post-9/11 wars - GZERO ... ›

- Farewell to the flip phone: How media has changed since 9/11 ... ›

- Hard Numbers: 9/11's enduring toll - GZERO Media ›

- 9/11 and after: A personal reminiscence from inside the machine ... ›

- The alternative versions of 9/11 - GZERO Media ›

- Podcast: A safer America 20 years after 9/11? Michael Chertoff and Rory Stewart discuss - GZERO Media ›

- Is America safer since 9/11? - GZERO Media ›

- US national security in the 20 years since 9/11 - GZERO Media ›

More For You

Xi Jinping has spent three years gutting his own military leadership. Five of the seven members of the Central Military Commission – China's supreme military authority – have been purged since 2023, all of whom were handpicked by Xi himself back in 2022.

Most Popular

Sponsored posts

Five forces that shaped 2025

What's Good Wednesdays

What’s Good Wednesdays™, January 28, 2026

Walmart sponsored posts

Walmart’s commitment to US-made products

- YouTube

In this episode of GZERO Europe, Carl Bildt examines how an eventful week in Davos further strained transatlantic relations and reignited tensions over Greenland.

- YouTube

In this episode of "ask ian," Ian Bremmer breaks down the growing rift between the US and Canada, calling it “permanent damage” to one of the world’s closest alliances.

An employee works on the beverage production line to meet the Spring Festival market demand at Leyuan Health Technology (Huzhou) Co., Ltd. on January 27, 2026 in Huzhou, Zhejiang Province of China.

Photo by Wang Shucheng/VCG

For China, hitting its annual growth target is as much a political victory as an economic one. It is proof that Beijing can weather slowing global demand, a slumping housing sector, and mounting pressure from Washington.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.