November 07, 2019

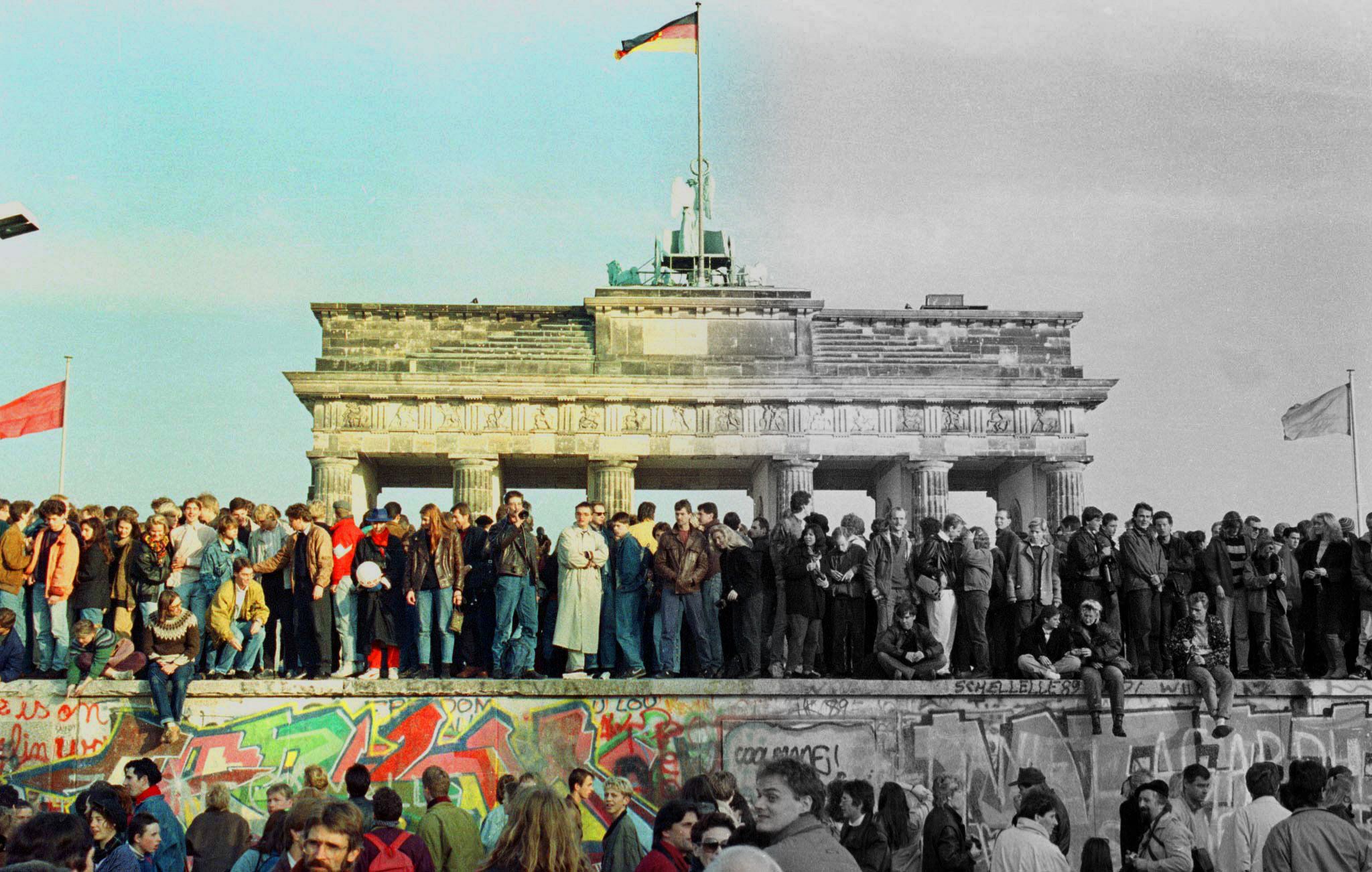

Thirty years ago, the Berlin Wall fell. Within months, the Soviet-backed governments of Central Europe were swept away by democratic systems. Two years later, the Soviet Union itself collapsed.

It's hard to capture just how extraordinary all that was at the time. Faced with popular protests, one of history's most fearsome empires had swiftly and (largely) peacefully melted away. Freedom had won. Police states had lost. Right?

But those events were seen in very different lights around the world. Here are three interpretations of 1989 that, in many ways, gave us the more troubled world of 2019.

First there was the 1989 of Western policymakers, who drew the conclusion that political and economic freedom were inevitable. This view opened the way to what we'd later call "globalization:" the rapid opening of economies to transnational flows of people, goods, and capital.

That delivered huge benefits to the world. It lifted a billion people out of poverty over the next 25 years. Entire continents joined the global middle class. Bankers and businesspeople got fabulously wealthy. Stuff got a lot cheaper. The internet came to change everything!

But that system eventually sparked a backlash among middle classes and rural communities in Europe and the US. They resented the offshoring of their jobs, the rising inequality of their societies, and the threats that a more globalized world posed to their ways of life. This is the arc that delivered Brexit, Trump, and the return of populism in continental Europe.

Second, there was the 1989of China, where the Communist Party concluded it must never, ever, relinquish political power. The crushing of the Tiananmen Square protests in June, followed by the fall of the Wall in November, convinced the Communist Party that while its ongoing economic liberalization was necessary, political liberalization was fatal.

In the coming years, China would prove wrong the Westerners who were certain – certain ! – that economic openness would lead to political freedom. Instead, the party harnessed economic growth to strengthen its grip. Now it's using new technologies to shore up its authoritarian system, and we're close to the moment when the world's largest economy is an opaque one-party dictatorship. The West believed wrongly that the global economy would change China's system: in fact, China's system changed the global economy.

Third, there was the 1989 of today's illiberal former liberals. The man who currently leads Hungary's avowedly "illiberal democracy" was once a shaggy haired dissident who helped bring down communist rule in his country. How is this possible? For men like Viktor Orban – or former dissident Jaroslaw Kaczynski, who leads Poland's ruling rightwing Law and Justice party – 1989 wasn't about the triumph of liberal democracy as such. It was about reclaiming national sovereignty after decades under Soviet rule.

Today, these leaders have exploited the economic and cultural anxieties of their shrinking populations to argue that the EU – which they joined in 2004 – is a new kind of oppressor whose liberal policies, particularly on migration, are a threat not only to their countries, but to Europe as a whole.

All of these interpretations of 1989 combined to give us the world we live in today. It's a world that is vastly more prosperous and free than it was before the Wall fell, but it's also a world where nationalism is rising, a new global rivalry is emerging between the US and China, and freedom is more fragile than we thought thirty years ago.

More For You

- YouTube

Is Venezuela entering a real transition or just a more volatile phase of strongman politics? In GZERO’s 2026 Top Risks livestream, Risa Grais-Targow, Director for Latin America at Eurasia Group, examines Delcy Rodríguez’s role as Venezuela's interim president after Nicolás Maduro.

Most Popular

It’s been just over 48 hours since US forces conducted a military operation in Caracas and seized Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro, and the future governance of the country – and the US role in it – remains murky.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.