February 20, 2018

As we continue to learn more about Russian efforts to influence the 2016 presidential election, let’s clear up a few things about what it actually means for a foreign power to hack an election. There are, broadly speaking, three different ways to do it:

1) Hack the vote by penetrating the voting systems and changing the actual vote tallies.

2) Hack the voters by spreading false information designed to shape their perceptions and influence their choices on election day.

3) Hack the mainframe of democracy itself by inflaming social tensions and sowing doubts about the integrity of the electoral process altogether, ensuring that whoever wins struggles to govern.

According to the latest Mueller indictment, there’s no evidence of Russian vote tampering — a point on which President Trump is particularly fixated — but Russians with Kremlin ties did, it would appear, do an awful lot of #2 as part of a broader effort to do #3.

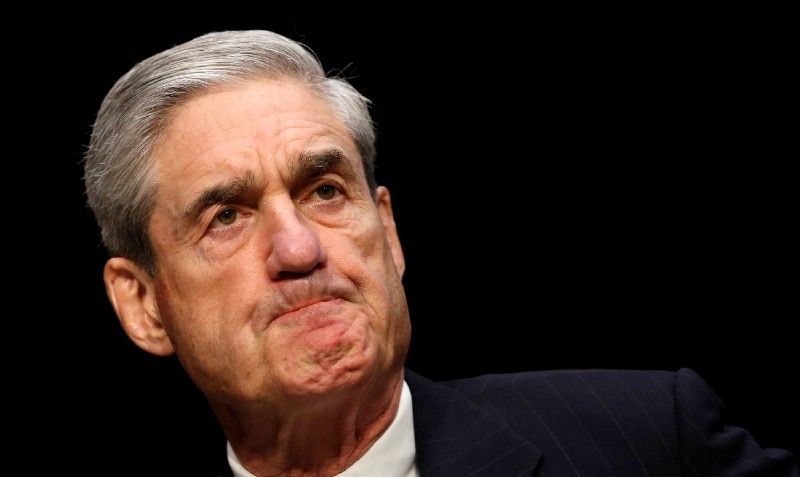

Whether the Trump campaign knowingly helped Russians with any of it is still a question to which only Bob Mueller can give us a definitive answer. And he may yet do so.

But more immediately there are two crucial questions:

The first is if and how to punish foreign powers for election meddling. There are sanctions sitting on President Trump’s desk, but they have so far not beenimplemented.

The second is how to prevent meddling from happening again. To defend against efforts to hack the vote, you can beef up cyberdefenses.

But repelling efforts to hack voters is much more difficult. One way is to regulate and police online content, but that raises thorny questions about the balance between freedom of speech and national security.

But there’s a deeper question here: why do so many people lack the skills, or even, it seems, the willingness, to discern between fake news and real reporting anyway? The underlying problems of socioeconomic polarization, plummeting trust in traditional media, and broader disillusionment with democracy itself are what makes the ground so fertile for influence operations in the first place. Addressing those is a much broader challenge. It’s not clear that the US, or anyone else, is close to figuring that out.

More For You

Xi Jinping has spent three years gutting his own military leadership. Five of the seven members of the Central Military Commission – China's supreme military authority – have been purged since 2023, all of whom were handpicked by Xi himself back in 2022.

Most Popular

Sponsored posts

Five forces that shaped 2025

What's Good Wednesdays

What’s Good Wednesdays™, January 28, 2026

Walmart sponsored posts

Walmart’s commitment to US-made products

- YouTube

In this episode of GZERO Europe, Carl Bildt examines how an eventful week in Davos further strained transatlantic relations and reignited tensions over Greenland.

- YouTube

In this episode of "ask ian," Ian Bremmer breaks down the growing rift between the US and Canada, calling it “permanent damage” to one of the world’s closest alliances.

An employee works on the beverage production line to meet the Spring Festival market demand at Leyuan Health Technology (Huzhou) Co., Ltd. on January 27, 2026 in Huzhou, Zhejiang Province of China.

Photo by Wang Shucheng/VCG

For China, hitting its annual growth target is as much a political victory as an economic one. It is proof that Beijing can weather slowing global demand, a slumping housing sector, and mounting pressure from Washington.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.