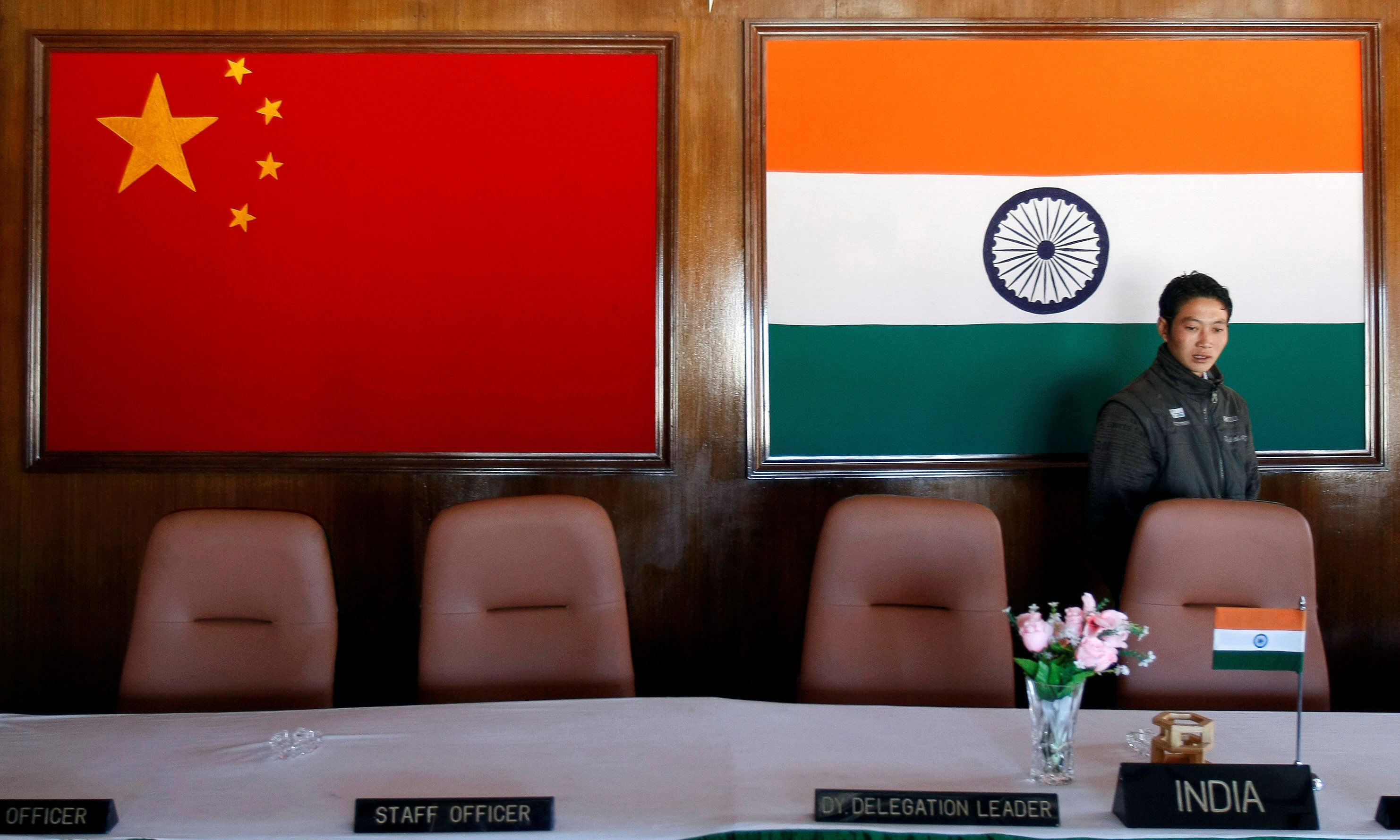

This week's skirmishes between Indian and Chinese forces in a disputed Himalayan border area represent the deadliest flare up between the two regional powers in many decades.

The two foes have been locked in a bitter border dispute for years, yet recurrent flare-ups have tended to be resolved through diplomacy. The spark that ignited the clashes this time seems to be a recent Indian infrastructure development, including a road to a remote Indian army base which New Delhi argues falls on its side of the Line of Control.

Though details remain murky, after the last rock was thrown Tuesday, at least 20 Indian troops were dead, while the People's Liberation Army also reported some "casualties" on its side, but stayed mum on the numbers.

How did we get here? India and China, the world's two most populous states and two great powers in Asia, have long viewed the other cautiously. Since China thrashed India's army in a border war in 1962, the two rivals have enjoyed a cold peace for the most part. But as Beijing and New Delhi have continued to compete for influence on many fronts across South Asia, the two nuclear powers are more often bumping up against one another in the remote borderlands, as well as elsewhere in South Asia.

The power of personality. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, first elected in 2014, India has tried to project a muscular nationalism at home and abroad. As part of this strategy, Modi has stoked national pride by talking tough on longtime rival Pakistan, which has cozied up to Beijing in recent years. (China, for its part, has endeared itself to Islamabad by pledging a whopping $60 billion to build the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor — a network of roads, pipelines and a crucial port.)

In asserting an expanded regional role for his country, Modi has made clear to China's leaders that there are limits to India's willingness to resolve ongoing conflict through peaceful negotiation. Consider that last year, after protracted skirmishes broke out in the contested western Himalayas in 2017, Modi moved unilaterally to carve out a chunk of Kashmir long contested by India, Pakistan, and China, placing it under direct rule from New Delhi. Unsurprisingly, this move irked Beijing, which said that it undermined its territorial sovereignty. Increasingly wary about China's dominance on its doorstep – in Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka – Modi signed a $3.5 billion arms deal earlier this year with the United States, a useful ally against Beijing.

Recent clashes also come as China has doubled down on its own territorial ambitions across Asia. Since coming to power in 2012, President Xi Jinping has stoked national pride in China's expanded military and economic influence and declared a "new era" for China's role in the world. This is part of what he has called the "great rejuvenation" of the Chinese state.

In recent months, as international attention has focused squarely on COVID-19, Beijing has gotten bolder, clamping down on Hong Kong's autonomy and clashing with Indonesian, Malaysian, and Vietnamese vessels in the disputed South China Sea – and probing Indian lines in the Himalayas, which led to this week's clashes.

No one wants an escalation. Both sides say they are keen to deescalate the situation, since this confrontation comes with costs and risks for both sides. But neither government wants to appear to be the first to back down, and a meeting between military officials on Wednesday failed to break the border standoff. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Modi warned that the death of scores of Indian forces "will not be in vain."

More For You

Violence is once again scorching Nigeria. On Sunday, gunmen killed three people and took several hostages, including a Catholic priest, during an early morning attack in the northern state of Kaduna.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

This week, India agreed to stop importing Russian oil amid US pressure. However, that may be easier said than done. In January, India imported approximately 1.2 million barrels of Russian crude oil every day.

In 1930, an American sociologist arrived in the capital of Liberia, a small country in West Africa, on an unusual assignment. Charles S. Johnson, trained at the University of Chicago, had never conducted research outside the United States before.