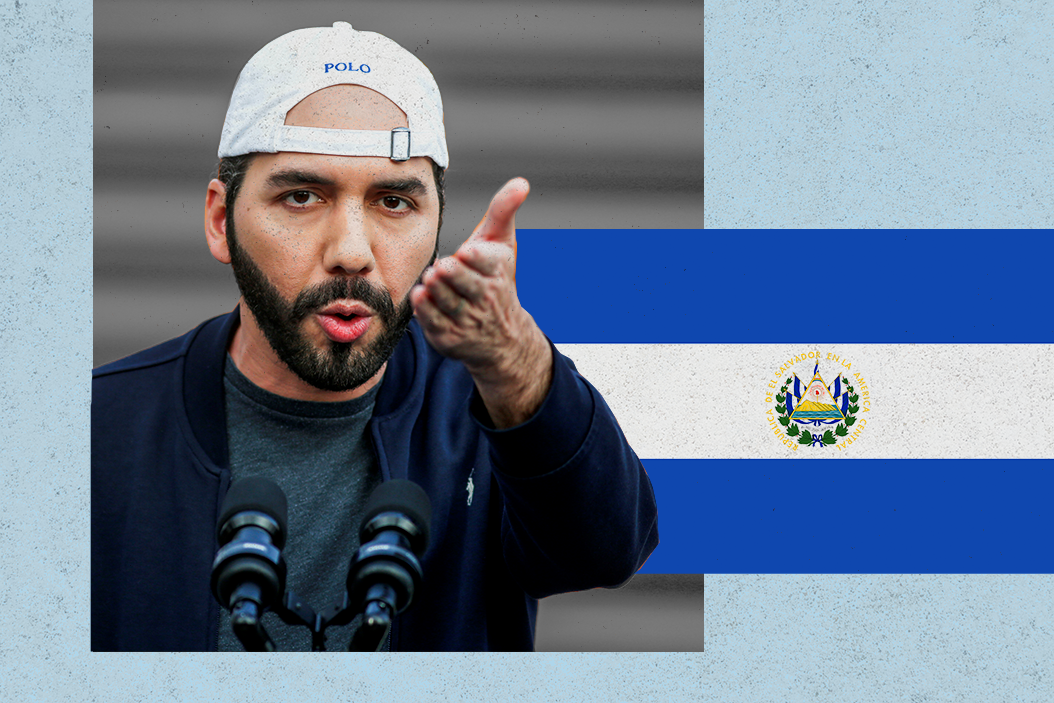

El Salvador's President Nayib Bukele is an unusual politician. The 39-year old political outsider boasts of his political triumphs on TikTok, dons a suave casual uniform (backwards-facing cap; leather jacket; tieless ), and refuses to abide by Supreme Court rulings.

Bukele also enjoys one of the world's highest approval ratings, and that's what helped his New Ideas party clinch a decisive victory in legislative elections on February 28, securing a close to two-third's supermajority (75 percent of the vote had been counted at the time of this writing).

His triumph will resonate far beyond the borders of El Salvador, Central America's smallest country, home to 6.5 million people. Now that Bukele has consolidated power in a big way, here are a few key developments to keep an eye on.

Anti-establishment fervor isn't disappearing. The recent election demonstrates that Salvadorians are buying what Bukele is selling even if he doesn't always deliver on his promises.

In 2019, Bukele came to power pledging to root out corruption, break the monopoly of the two parties that have run the country since the end of the civil war in 1992, and rid the country of violent gangs (El Salvador has one of the world's highest crime rates). Despite a dip early in the pandemic, crime has risen at various stages since — though Bukele has harshly cracked down on gang violence. Meanwhile, investigations reveal that Bukele's administration has been mired in its own corruption scandals. Still, a majority of Salvadorians (roughly 90 percent) see Bukele as preferable to a corrupt political establishment that has long lined its own pockets while poverty plagues around 30 percent of the population. People simply want change.

And this trend isn't unique to El Salvador either. In nearby Mexico, populist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as AMLO, also has failed to make good on some reform pledges that brought him to power in 2018. Still, polls show that Mexicans are overwhelmingly rooting for AMLO — a rugged self-described "man of the people" — in upcoming midterm elections, over a self-enriching political class that they feel has left them behind.

Like in Mexico, there are concerns about El Salvador's authoritarian drift. Last year, Bukele sent troops into the parliament to demand the legislative body approve his security package. "Bukele's style of governing is bullying," said Carlos Dada, founder of the newsite El Faro.

And now that Bukele has a supermajority, analysts warn that he can go even further, claiming a mandate to pack the Supreme Court, reconfigure the attorney general's office, and could even push for a new constitution, scrapping provisions that would cap his current presidency at one-term (consecutive terms are banned). Critics are worried that in placing his allies in control of all levers of government, Bukele can now effectively undermine all judicial and legislative independence.

Why does this matter beyond El Salvador? Political instability in El Salvador breeds regional insecurity and more migration.

People from the so-called "Northern Triangle'' of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras have for years constituted the largest share of migrants stopped at the southwestern US border. If an increasingly-authoritarian Bukele is unable to make good on his promises and improve Salvadorians' lives (New Ideas' success is so far rooted in Bukele's own self-styled image rather than a fixed political ideology) this could result in thousands fleeing in search of a better life in the United States, just as President Biden is trying to diplomatically tweak US foreign policy towards Latin America. The Biden administration recently axed the Trump administration's third country resettlement program (also known as the Remain in Mexico program), while still towing a tough line on what it calls "irregular migration." This complicates things for Biden who needs to work with the Salvadorians to manage the immigration issue, but who also can't be seen to be playing nice with norm-breaking Bukele after putting human rights and democracy at the heart of US foreign policy.

For Mexico, meanwhile, the stakes are also extremely high. The spillover effects of drug trafficking and gang violence in El Salvador create insecurity and havoc in Mexico (and vice versa). This dynamic intensified under the Trump administration's zero tolerance policy, when Mexico City experienced a surge in asylum applications from El Salvador. (Consider that in 2019, Mexico received around 80,000 asylum applications because many Central Americans did not want to risk being rejected at the US border and being sent back to their home countries.)

Looking ahead. The very online Bukele represents a new brand of politician sweeping parts of Latin America — and the globe. But in the year 2021, what happens in El Salvador very much does not stay in El Salvador. Mexico, the United States, and many others, are watching.

More For You

As Trump looks for new ways to pressure Tehran, backing Kurdish militants could open a volatile new front—alarming Turkey and risking a dangerous escalation.

Most Popular

Think you know what's going on around the world? Here's your chance to prove it.

The US and Israel have weapons and defense systems that are far more sophisticated than Iran’s. Precision missiles. Advanced radar. Missile defense systems stacked on top of each other.