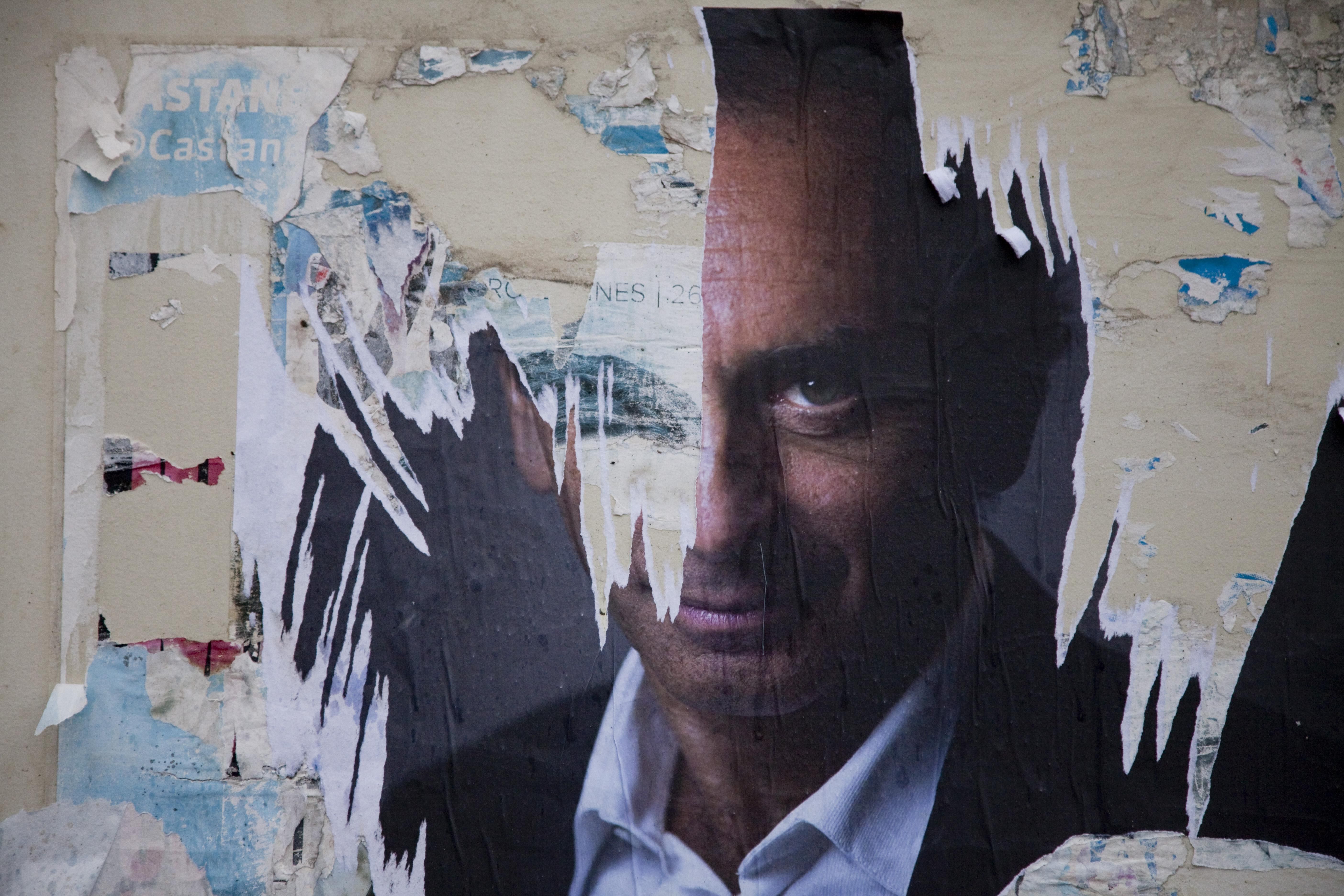

He has been convicted of inciting racial hatred. He wants to stop immigration and force Muslims to take Christian names. He thinks women wish to be dominated by men. He says France's wartime Nazi collaborators were actually good for the Jews. His name is Éric Zemmour and he is, at the moment, the biggest sensation in French politics.

Over the past several months Zemmour, an outspoken far-right TV personality, has surged in the polls ahead of next April's presidential election. Although Zemmour hasn't formally entered the race, one recent survey placed him second only to beleaguered President Emmanuel Macron, surpassing even Marine Le Pen, stalwart of the French hard right.

So, who is this guy?

Zemmour, the son of Jews from Algeria, is not a politician. He began his career as a journalist and quickly found a perch as a firebrand rightwing provocateur on TV and radio, lamenting what he sees as the decline, Islamization, and emasculation of France.

He is, to borrow a term from American radio, a "shock jock" of the highest order, albeit one who delivers his controversial ideas in a suit and tie, writes them in bestselling books, and wraps them in a smoky air of intellectualism that plays well in France.

And he's having a moment right now — for two important reasons.

For one thing, he is filling a gap left by Le Pen who, after placing second in the last presidential election, is trying (again) to soften her image and broaden her appeal. Zemmour's rise has, polls show, come chiefly at her expense. He speaks to the racial and cultural anxieties of a sizable swath of the French right, and slakes a broader thirst for politicians who don't give a damn about the establishment's high-handed politesse politique.

And the media just can't help itself! As Zemmour's outrages get more attention, he rises in the polls, meriting further coverage. According to a study reported by Politico, he got more than ten times as much TV attention in France as Le Pen did last month. If that perilous feedback loop sounds familiar to veterans of the 2016 US presidential campaign, Zemmour welcomes the comparison with former US president Donald Trump, a man with a similarly uncanny ability to make good use of a hostile media.

With Macron's approval rating languishing in the low 40s, could Zemmour really shake up the presidential race? Yes, but not because he has any serious chance of winning himself. Remember, France has a runoff presidential voting system — if no one cracks 50 percent in round one, the two top finishers face off in a second bout. Most polls show that if either Le Pen or Zemmour make it to the second round, Macron would win handily.

But there is a danger to Macron. First, Zemmour's rise has pulled the focus away from issues Macron is comfortable on — such as managing the pandemic, European leadership, and the economy — and towards issues where he is weaker, such as security, French identity, and culture wars.

Second, and more pressing, if Zemmour and Le Pen — who are already squabbling — split the rightwing vote in round one, that could open the way for a more formidable center-right candidate to challenge Macron in round two. That might be a problem for him.

Although the French left is currently a shambolic circular firing squad, the center-right Les Republicains party has an opening to field a candidate who can give Macron a run for his money next year.

That is, if Les Republicains can agree on a candidate. At the moment, the leading contenders are Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier, whom party elites seem to favor, and Xavier Bertrand, the plainspoken president of the Hauts-de-France region in Northern France, who "smashed the jaws" of Le Pen's party in recent regional elections and is already tied with Zemmour in some polls.

Le upshot. Irrespective of whether Zemmour has a chance to win the presidency, his message and his rise have already shaken up the race, and could reshape the French right for years to come.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article stated that Le Pen had come in second in the last two French presidential elections. This is incorrect. She placed second to Macron in 2017, but in the previous election she did not make it to the final round, which was between Nicolas Sarkozy and the eventual winner, Francois Hollande. We regret the error.