The European Union confirmed on Monday that it has reinstated sanctions on Iran over its nuclear program, following the United Nations’ decision over the weekend to reimpose its own penalties.

The move piles fresh punishment onto an economy already battered by a collapsing currency, soaring inflation and deficits, and chronic shortages of water and energy. Iran is also still reeling from the 12-day war in June, which included US airstrikes on its three main nuclear sites and a wave of Israeli attacks on sensitive government targets.

What’s in these sanctions? They reinstate bans on arms imports and on the transfer of dual-use technologies that could support a nuclear program. The measures also freeze the assets of individuals linked to Iran’s missile and nuclear efforts, impose travel bans on sanctioned officials, and authorize inspections of Iranian cargo, including oil shipments. All of this comes atop extensive financial sanctions that the US has imposed since 2018.

Why are they called “snapback” sanctions? They were previously lifted, as part of a 2015 nuclear deal between Iran, the US, and Europe, on the condition that Iran continue to allow international inspection of its nuclear programs to ensure that they are for peaceful use. The US exited that deal in 2018, reimposing sanctions, but European partners continued some of its terms. After the war with Israel, Iran suspended access to inspectors, opening the way for these sanctions to automatically “snap back” into place.

Economic impact. The effects are already rippling out over Iran’s currency markets. The rial is now trading at more than a million per US dollar and fell another 4% on the black market on Saturday. That slide is eroding the purchasing power of the middle class and squeezing quality of life. Eurasia Group Iran expert Greg Brew described the sanctions’ practical impact as “largely symbolic and psychological,” warning that they will deepen public disillusionment by reducing prospects for diplomacy and long-promised sanctions relief.

“The impact of the last few years of sanctions has been to increase inequality in Iran,” says Brew. “More of the wealth and more of the power is moving upward, while the middle class has been squeezed and shrunk.”

Could that generate a fresh wave of protests? Possibly, as Iran has seen a number of economic-driven protests in recent years. But the political impact would likely be limited, in Brew’s view."Iran has no organized political opposition,” he says, “There's really no locus around which the opposition can mobilize and the internal repressive apparatus is still as large and as powerful as it has always been, if not more."

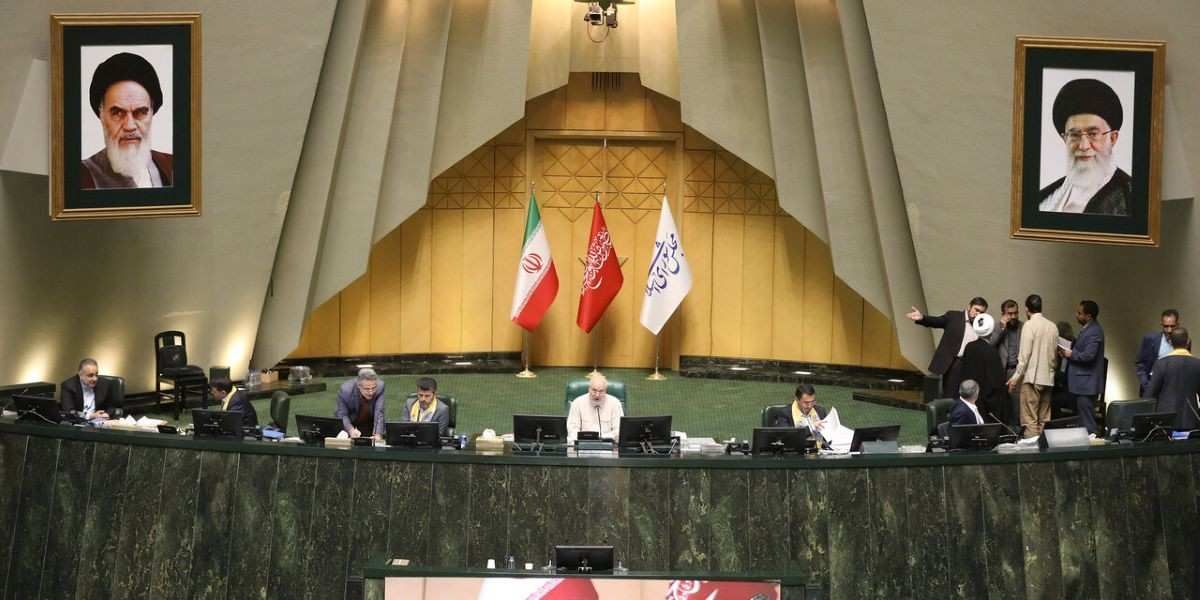

Nuclear diplomacy stalled. The purpose of the sanctions is to pressure Iran to return to meeting its obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which requires Tehran to forswear nuclear weapons development and accept international inspections.

"What we're looking at in the short term is Iran remaining within the NPT in name only," says Brew. Since the 12-day War, Iran has been skirting the treaty’s spirit by denying inspectors access to key facilities and refusing to clarify the status of its enriched uranium. The regime has made the decision to weather more sanctions rather than allow international inspections, underscoring the question: what, exactly, is going on at Iran’s nuclear facilities now?