Andrew Crook, a fish and chip shop owner in the northern English town of Euxton, has been in the industry for so long, he says, that he’s got “vinegar in his blood.”

Crook has seen plenty of ups and downs at work. But the 46-year-old says he’s never seen anything quite like the storms shaking the industry now, as the effects of the war in Ukraine put an iconic British industry on the brink of disaster.

“It’s a bleak picture,” Crook tells us from his home in the nearby town of Chorley, just as a loud shriek interrupts the conversation. “I’ve got a macaw,” he explains. “He can tell when I’m on a call, and he likes to join in.”

Even before Russia invaded Ukraine, the chippies were struggling because higher fuel costs caused by the pandemic were forcing fish trawlers to charge more for their haul.

But Russia’s war in Ukraine has made things even worse. The two countries together produce 75% of the world's sunflower oil, the preferred fry bath for chippies. As the conflict rages, sunflower farming and processing have ground to a halt, while Russian naval blockades and Ukrainian sea mines have crippled exports from Ukraine’s Black Sea ports. Global prices have soared to record highs.

Crook, who also heads the UK’s National Federation of Fish Friers, an industry group, says the cost for 20 liters of Ukrainian sunflower oil has nearly doubled to 50 pounds ($62). The cost of alternatives like Malaysian palm oil is also rising, particularly after Indonesia, a rival palm oil producer, briefly halted its own exports to protect local consumers.

Meanwhile, the industry is bracing for a further blow as the UK prepares to slap an “imminent” 35% tariff on imports of Russian fish as part of a broader sanctions package against Moscow.

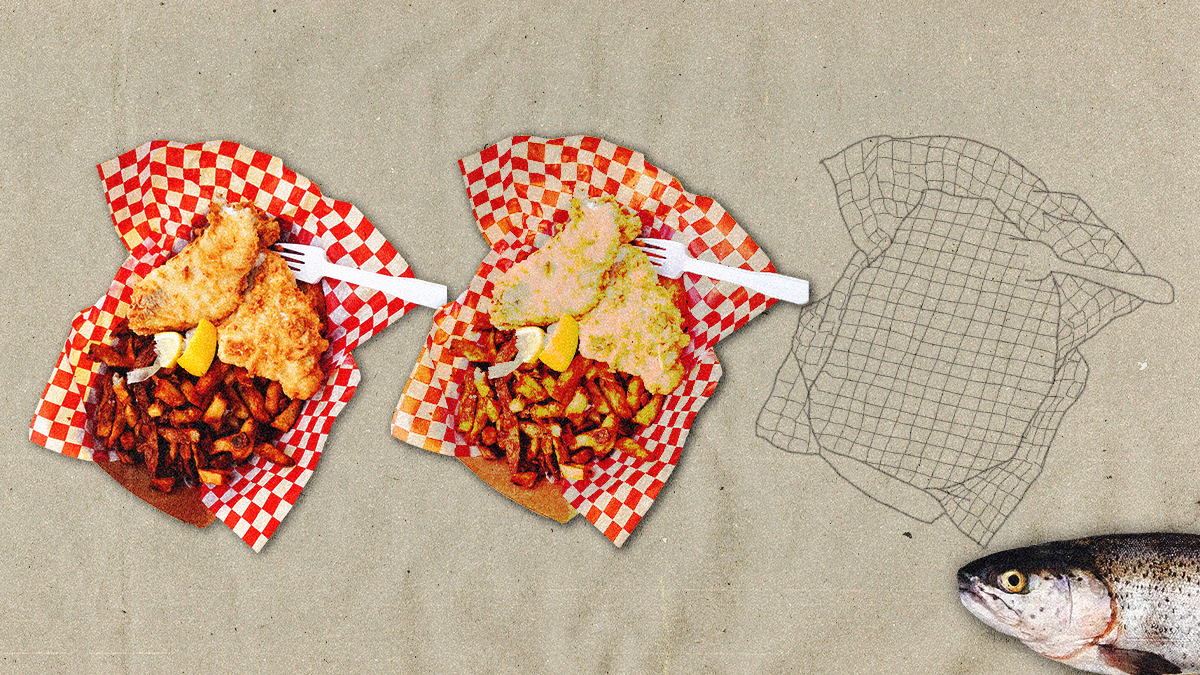

The dish on fish and chips. Known as a cheap, hearty meal that's high in protein and calories, fish and chips first appeared in the UK in the 1860s, when industrial-scale fish trawling came into its own.

The dish quickly became a staple food for the British working class. In fact, during World War II, even as the government was rationing tea, butter, and meat, fish and chips got an exemption to ensure the country's factory workers were well fed for the war effort.

Today there are more than 10,000 chippies across the UK, with an annual turnover of more than $1.5 billion, according to the Federation of Fish Friers.

Crook says that their role in the working-class towns of England goes beyond mere meals. They sponsor local football clubs and charities and even help to keep an eye on people who have no one else to care for them.

“Some of the old people that come into fish and chip shops, we might be the only person they speak to all day,” says Crook. “If they don't come in for a week you do notice, and you start asking around and making sure they're okay.”

But the new price pressures are already forcing many chippies to close. Crook says that a third of them could go out of business over the next nine months.

Alex Kliment explores the latest in fish and chips on GZERO World with Ian Bremmer. Watch the video above.

To survive, the chippies are adapting. Some are offering smaller portions, while others are raising prices or supplementing fish with cheaper proteins like sausage. The crisis has also spurred innovation, he says, with entrepreneurs exploring the use of catalytic converters to treat the frying oil so that it can be reused for longer.

But even amid this whirlwind of challenges, Crook is optimistic that the 160-year-old industry will find a way to survive.

“If anyone's ever been over to a UK fish and chip shop, they know there’s not many shy and retiring shop owners,” he says.

“We’re quite loud and boisterous, and we're not known for quitting.”

Watch the full interview above.

Additional reporting by Sarah Kneezle.

This comes to you from the Signal newsletter team of GZERO Media. Subscribe for your free daily Signal today.