Welcome to this special edition of Signal where we'll look at the question of how politics and markets are shaping the drive for "sustainability." This edition is part of a joint project between GZERO Media and Citi Private Bank called "Living Beyond Borders."

-The Signal team

Wait, before we get started here — what is sustainability anyway? Good question! "Sustainable" business practices are those that minimize negative impacts on the environment and society, in ways that make them "sustainable" over the long term. In recent years, the effects of climate change and resource depletion have caused soaring interest in "sustainability." And to make sustainable practices not only virtuous but also lucrative, governments nurture them by creating incentives, including subsidies for renewables, caps on emissions, or clear regulatory standards for what counts as "sustainable" in the first place.

Because this all involves tradeoffs and compromises between interest groups (and even countries), it's inherently political. And that's why we're here to talk about it. First up, a look at a big moment for the most important sustainability-related pact in the world… the Paris Climate Agreement..

The US is rejoining the Paris Climate Accord. What comes next?

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiWhile the US played a major role drafting the Paris Climate Accord, a 2015 global treaty aimed at mitigating the effects of climate change, it was also the only country out of nearly 200 signatories to pull out of the landmark pact.

Now President-elect Biden says he will rejoin the accord on day one of his administration in January. But while rejoining the treaty in practice is relatively straightforward, Biden will face plenty of political challenges at home — and abroad — once the US is back in the mix.

So what comes next for the Paris Climate Agreement, and how might things change once the US is back on board?

How does the US rejoin the pact? Biden can rejoin the pact by issuing an executive order, and then sending a letter to the UN stating the US' intention to opt back in. That's the easy part.

The problems come once the US is back in the fold. First, the Biden administration will have to set new goals for reducing carbon emissions by 2030 through domestic initiatives. While these are voluntary non-binding targets, Washington will have to provide regular reports to the UN on its progress. These check-ins are not optional.

Biden's goals. The president-elect says that he will recommit the US — the world's second largest producer of carbon dioxide in absolute terms — to emissions reduction goals, including a $2 trillion investment in clean energy sources during his first term. Biden has also said that he'll tie the US' post-pandemic economic recovery to clean job initiatives, and that under his watch, the US will resume its global leadership role in tackling climate change.

Will domestic politics allow Biden to pull this off? While many members of the Democratic party will surely be relieved that the US has renewed its commitment to Paris, progressives like Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Bernie Sanders have been pushing Biden to go even further. But to date, Biden's support for ambitious policy initiatives like the Ocasio-Cortez sponsored Green New Deal — which aims to revamp every building in America to be more energy-efficient and create clean-energy jobs — has been inconsistent.

Biden has tried to appeal to Americans in states like Pennsylvania and Ohio who still rely on jobs in fossil fuel industries (as well as moderate Republicans), while trying not to alienate progressives within his own party. This balancing act will only get harder as the post-pandemic recovery takes center stage in 2021 — and tensions within the party will likely get worse once Biden is actually in the White House.

Additionally, after a tumultuous four years of the Trump administration, which prioritized rolling back domestic climate policy, the incoming Biden administration will have a lot of rolling back (or forward, depending on your perspective) to do of its own. While some of this can be done through executive order, Biden's goal of making the US carbon-neutral by 2050 relies on sweeping action from the US Congress — and to go deep he needs the Senate to turn blue when Georgians head to the polls next month in an election that will decide control of the chamber.

Meanwhile, on the global stage, lack of US leadership has undermined efforts to tackle climate change in recent years. With the US responsible for almost 15 percent of global emissions, any meaningful advances on decarbonization require Washington's cooperation. But climate-related innovation and diplomacy, traditionally driven in large part by the US, have stalled in recent years under the climate-skeptic Trump administration.

What's more, the abdication of US leadership on climate action has undermined relations with other nations, including both wealthy allies and developing countries that rely on US support to help them meet their own mitigation goals. (The US originally pledged $3 billion to help poor countries quit fossil fuel use, but the Trump administration slashed the budget by two thirds.)

But while the US has been missing in action, China has extended its Paris commitments, pledging to become carbon-neutral by 2060, a massive feat for the world's largest carbon emitter. "It is precisely because the Communist Party regime is bent on shaping the next century that its leader takes climate change seriously," Adam Tooze, who spoke to GZERO Media this past spring, wrote in Foreign Policy.

Meanwhile, the EU has also set a net zero carbon goal by 2050, and has made climate action a key part of its post-pandemic recovery effort. Major economies including the UK, South Korea, and Japan have made similar pledges, while India, the world's third largest emitter, has also committed to stronger climate action.

Though China and the EU are largely setting the global climate agenda, neither of them has America's economic scope or power, which is crucial to getting countries all around the world to take the threat of global warming seriously.

Looking ahead: In order to make meaningful global change on decarbonization, the US needs to be at the front of the pack. But rebuilding trust, and leadership bonafides, after taking a back seat for four years will surely take time.

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

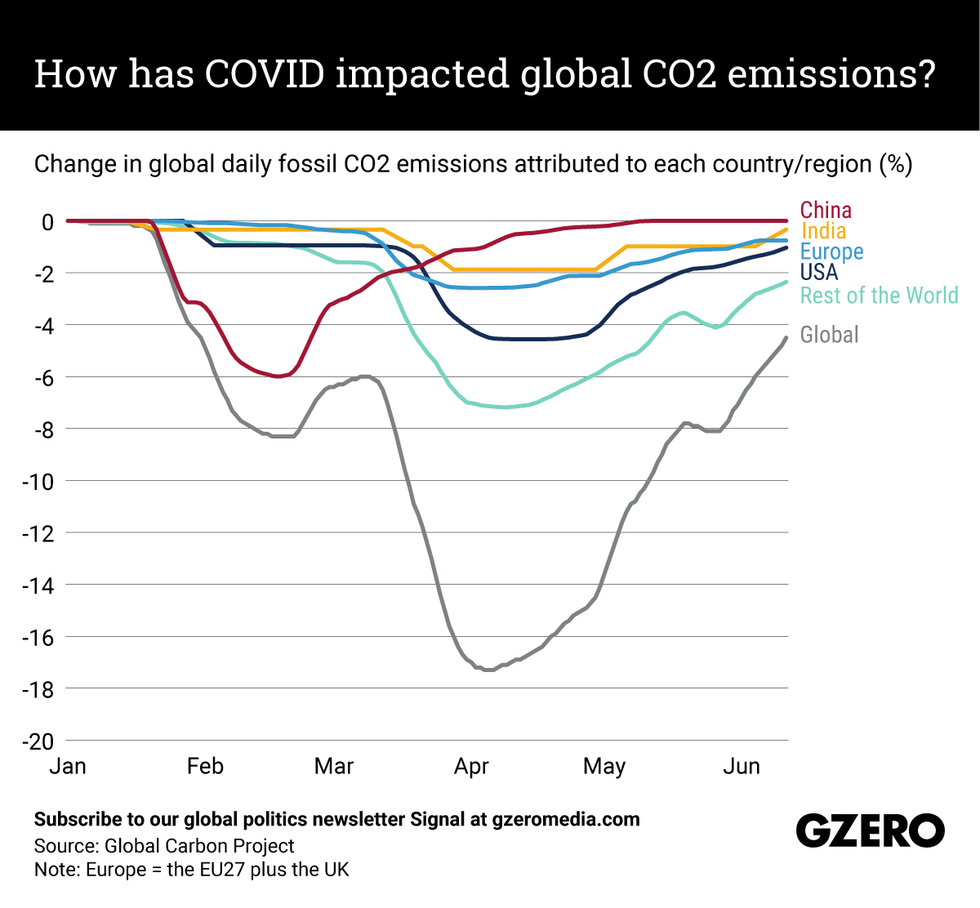

Gabrielle DebinskiDuring the early months of the pandemic, scientists announced some rare good news in a hellish year: as energy demands fell because of stay-at-home policies, global carbon emissions plummeted. Some hoped the impact might be long lasting. But mere months later, as the pandemic recovery has picked up in many countries, greenhouse gas emissions have ramped up again, reaching pre-pandemic levels in many places. Here's a look at the amount of carbon dioxide produced in several regions and countries during the first six months of 2020.

Investing for a post-COVID world

Citi Private Bank

Citi Private BankAs the virus departs in 2021, the global economy will recover more quickly and robustly from the COVID recession than from a more typical large downturn. The backdrop this optimistic outlook is the remarkable resilience seen despite the pandemic.

Read the full report, learn more about key themes in the report, and view related videos.

What We’re Watching: The politics of ESG, the priorities of “Renewable China”, and the Big Losers in all of this

Carlos Santamaria

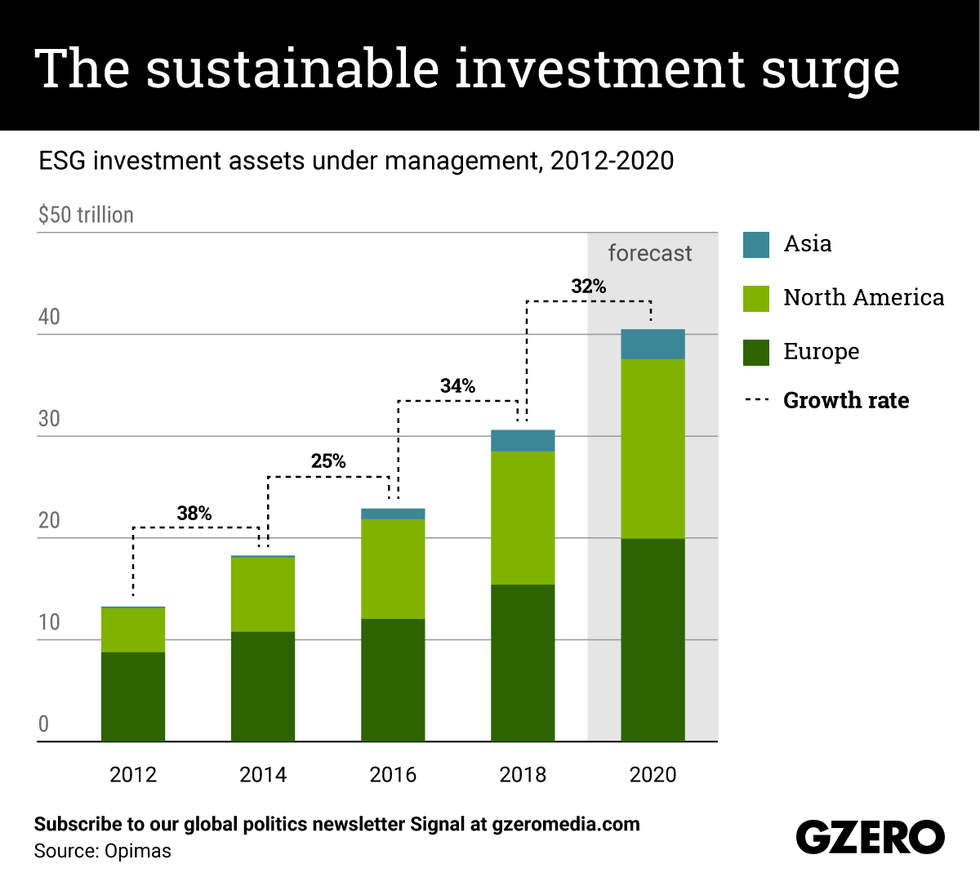

Carlos SantamariaThe future of ESG: Global investor interest in supporting sustainable companies has soared in recent years. But how do you define "sustainable"? One widely used criteria is ESG, which stands for "environmental, societal, and (corporate) governance." The catch, however, is that there still isn't a uniform definition of ESG criteria and regulation across different markets. For example, the EU and the US — home to the largest financial markets in the world — still disagree on the basic question of whether pension funds can classify or not. Meanwhile, outside of these two markets and some parts of Asia, the concept of ESG is relatively scarce in much of the developing world. So, what about China, where the sustainable investment market remains virtually untapped? If the Chinese join the party, it could be a game-changer. The larger the ESG market, the more lucrative it can be — and the better that is for society and the planet. But that means that the world's three largest economies, which hardly see eye-to-eye on anything these days, will have to agree on common standards for global ESG investment to truly take off. We're watching to see if and how that might happen.

Renewable China: The world's second largest economy pollutes — a lot. But China has also in recent years emerged as a leader in renewables investment. Why? One reason is that Beijing is increasingly worried about the security of its massive oil imports. Much of those come from the Middle East, where China has relied for decades on the US to provide security. But now that the US itself is a leading oil producer, Washington is less interested in the region, making China more vulnerable to supply disruptions there. At the same time, China's heavy reliance on coal-fired energy plants has poisoned China's air and water, and even stoked unrest. All of this has prompted the Chinese government to become, in recent years, an industry leader in the development of renewables like solar and wind power technologies. China is also the world's largest maker and buyer of electric cars. One big thing to watch here is how much China cooperates with other economies -- particularly the US. Are we headed for a world where the two largest economies are green tech rivals or partners?

Those who see red in a greener world: The sustainability revolution is undoubtedly good for the planet and, as we've seen, for financial investors too. But spare a thought for those who have the most to lose in all of this: oil-exporting economies. Even before the coronavirus pandemic kneecapped global demand for oil — briefly sending prices into negative territory — they faced big challenges. The shale oil revolution in the US had whittled away American demand for foreign crude. Emissions reduction and renewables policies in the US, China, and Europe were undercutting long-term demand for what the Saudi Arabias, Russias, Nigerias, Venezuelas, and Iraqs of the world sell. In these countries, oil delivers more than two thirds of export earnings and is the bedrock of the budget. Over the next decade, oil exporters have tough choices to make about how to diversify their economies. Demographic pressures make the problem especially acute in the Middle East and Africa: in Saudi Arabia and Nigeria, for example, more than two thirds of the population is under 30. Even when oil prices were high, the energy industry wasn't going to provide enough good jobs for them. Countries with bigger rainy day funds, like Saudi Arabia or Russia, may have more time to figure this all out. But what of cash-strapped Iraq or economically-wrecked Venezuela?

The Graphic Truth

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos SantamariaAs more investors back responsible businesses and funds, the growth of assets under management that are ESG compliant (under one standard or another) has been soaring in recent years. What's more, the geographic scope of this market is growing. A few years ago it was mainly big in Europe , but it's now picking up fast in the US and expanding to Asia, driving a massive boost this year alone. Why? By throwing a glaring spotlight on global inequality, the thinking goes, the pandemic has been a major driver of investment that focuses less on hard profits and more on socially and environmentally responsible capital management. Will this sustainability surge carry on next year? We take a look at ESG investment's upward trend over the past eight years — globally and by region.

Podcast: Can sustainable investing save our planet?

Two centuries ago, Benjamin Franklin called on American business leaders to "do well by doing good." He believed that companies could be profitable while also fostering healthier and happier communities. Today, amid a pandemic that has laid bare acute economic, social, and environmental problems around the world, that challenge is more pressing than ever. How can investors meet it? Learn more in this podcast featuring Harlin Singh, Head of Sustainable Investing at Citi Private Bank; Elree Winnett Seelig, the Head of ESG for Markets and Security Services at Citi; Rohitesh Dhawan, Director of Global Energy and Natural Resources at Eurasia Group; and Gerry Butts, Eurasia Group's Vice Chairman.

Hard Numbers: Coal still king in Asia, EU to cut emissions, ESG in the Global South, COVID’s tiny temperature impact

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos Santamaria638 billion: Investors have poured $638 billion into new coal power plants around the world, with more than 80 percent of them in Asia. Analysts predict that most of these projects will go ahead despite falling demand and environmentalist pushback, as many Asian governments seek to protect their coal sectors from the economic impact of COVID-19.

55: European Union leaders have agreed to cut carbon emissions by at least 55 percent compared to 1990 levels by the end of the decade. The new commitment — included in the EU's hard-fought deal on a $2 trillion coronavirus rescue package — is in line with the bloc's overall pledge to reach "net zero" emissions by 2050.

6: Only six of the world's top 100 most sustainable companies are based in the Global South. Three are in Brazil, two in China, and one in South Africa. While ESG-compliant businesses are doing well in many rich nations, ESG has yet to take off in most developing countries, mainly due to vague ESG criteria and market barriers that limit the flow of global ESG investment to many emerging economies.

0.01: The pandemic pushed global carbon emissions down by more than 7 percent this year, the biggest annual drop since World War II. That, however, will only lower global temperatures by a "negligible" 0.01°C thirty years from now.Follow us on Twitter and Instagram. If a friend sent you this email, you can subscribe here.

This edition of Signal was written by Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. The art and graphics were made by Annie Gugliotta, Paige Fusco, and Gabriella Turrisi.