Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

Living Beyond Borders Newsletters

The influence of artificial intelligence is already pervasive, and its potential for disruption – from scientific advances to job market shifts – means it also has serious political implications.

In this special edition of GZERO Daily, in partnership with Citi Global Wealth Investments, we look beyond the debate of whether AI will be good or bad – it will be both! – to the need for savvy political management during this tumultuous transition period.

Below, you’ll find:

- A few handy definitions

- Revolution vs. regulation

- AI’s political impact

- A rat regime

- Plus: A podcast on AI and what it means for democracy

Thanks for reading.

– The GZERO Daily team

Before we go on: What are we talking about?

If you’re confused about the difference between “Automation,” “AI,” and “Generative AI,” that’s OK! They’re all related but distinct terms:

- Automation is the use of robots to perform repetitive tasks based on pre-determined rules. (Slap together widgets on an assembly line).

- Traditional AI recognizes patterns in vast sets of data and proposes (or even makes) decisions based on it. (Identify parts of the widget factory that are producing components less efficiently and identify why that is).

- Generative AI draws on data sets to produce “original” works of thought, analysis, coding, or art in response to prompts. (Design a better widget for us, or handle all customer service calls about our widgets).

What We're Watching: Requests for regulation, power of personal prejudice, revolutionary potential

REUTERS/Dado Ruvic

Regulate AI: Sure, but how?

AI revolutionaries like OpenAI CEO Sam Altman want government regulation, and they want it now – before things get out of hand.

The challenges are many, but they include AI-generated disinformation, harmful biases that wind up baked into AI algorithms, the problems of copyright infringement when AI uses other people’s work as inputs for their own “original” content, and, yes, the “Frankenstein” risks of AI-computers or weapons somehow rebelling against their human masters.

But how to regulate AI is a big question. Broadly, there are three main schools of thought on this. Not surprisingly, they correspond to the world’s three largest economic poles — China, the EU, and the US, each of which has its own unique political and economic circumstances.

China, as an authoritarian government making an aggressive push to be a global AI leader, has adopted strict regulations meant to both boost trust and transparency of Chinese-built AI, while also giving the government ample leeway to police companies and content.

The EU, which is the world’s largest developed market but has few heavyweight tech firms of its own, is taking a “customer-first” approach that strictly polices privacy and transparency while regulating the industry based on categories of risk. That is, an AI judge in a trial deserves much tighter regulation than a program that simply makes you uncannily good psychedelic oil paintings of capybaras.

The US is lagging. Washington wants to minimize the harms that AI can cause, but without stifling the innovative brio of its industry-leading tech giants. This is all the more important since those tech giants are on the front lines of Washington’s broader battle with China for global tech supremacy.

The bigger picture: This isn’t just about what happens in the US, EU, and China. It’s also a three-way race to develop regulatory models that the rest of the world adopts too. So far, Brussels and Beijing are in the lead. Your move, Washington.

Regulation can’t address what people want

The emergence of AI has amplified the problem of disinformation that has proliferated since the 2016 US presidential election, and regulation is often touted as a way to address this worsening issue.

But even if governments do find a way to effectively regulate AI – and that’s a big if – that doesn’t address the widespread demand for conspiracy theories that confirm people’s established political and cultural biases.

Indeed, in this hyper-charged partisan environment, the desire to create and access this sort of content has only grown – and AI is about to supercharge it.

In some instances, it already is: The campaign of GOP presidential candidate and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis recently shared AI-generated fake images of Donald Trump, his main rival, embracing Dr. Anthony Fauci, a divisive figure within right-wing political circles. Many DeSantis followers bought it, despite the photos’ authenticity being debunked.

This, of course, is nothing new. People say they want access to truthful information, but research suggests otherwise. For example, when researching misinformation in 2020, Australian analysts found that “unless great care is taken, any effort to debunk misinformation can inadvertently reinforce the very myths one seeks to correct.” Demand for information that confirms personal prejudices runs rampant. Loosely regulating AI is not going to quench that thirst.

The revolutionary AI upside

In years to come, experts tell us that artificial intelligence will alter societies and change individual lives on a scale greater than changes brought about by the creation of the World Wide Web. In the process, AI will create challenges and risks that deserve careful consideration. But headlines that warn of catastrophe are hiding the revolutionary advances and opportunities that will benefit billions of people.

By sifting quickly and efficiently through oceans of data, AI will help scientists and researchers develop new treatments, and even cures, for diseases, including cancer, that will no longer kill large numbers of people. It will help educators individualize the instruction of vast numbers of children, lifting young people everywhere much closer to their natural potential. By inventing new ways of working, AI will sharply increase economic productivity, an essential step in raising living standards.

Even as people around the world are made healthier, better educated, and more prosperous by these advances, no one should underestimate the upheaval created as human beings adapt to them, and there is ample reason to fear that benefits won’t be evenly shared – within countries or across borders.

How AI will roil politics even if it creates more jobs

Alex Kliment

Alex KlimentWhether artificial intelligence will ultimately be good or bad for humanity is an open debate. But there’s another, more immediate issue that often gets lost in the scrum: Even if AI eventually creates more jobs and opportunities than it destroys, what happens to the actual people who lose their jobs on the way to that happier future? And how might their grievances shape politics in the meantime?

Think of the people who once earned a living by building or driving horse-drawn carriages. In a matter of years at the beginning of the last century, railroads and the nascent automotive industry erased their livelihoods entirely. Yes, those sectors ended up creating vastly more jobs than they killed, but it was tough luck for those in the buggy industry who weren’t able to learn new skills or move to those new jobs in time.

The same goes for US manufacturing workers whose jobs were shipped off to China or Mexico in the 1980s and 1990s. Or today’s Bangladeshi garment workers, who are threatened by US robots that can now make textiles better and faster than humans can. Although globalization and offshoring increased most people’s standards of living globally, that’s cold comfort for the people who were left jobless as a result.

And so it is today with AI. Between now and the time when AI is fully and beneficially integrated into all aspects of many existing (and new) jobs, a lot of people are going to lose their work and will quickly find themselves in a sink-or-swim situation that forces them to learn new skills, fast. Can they?

We don’t know who those people are just yet. White collar workers like coders, paralegals, financial analysts and traders, or (gulp!) journalists and creatives? Call center workers in emerging markets like the Philippines, where the industry accounts for as much as 7% of GDP?

But they will have real grievances and powerful platforms that can disrupt politics quickly. Whoever gets edged out by AI, the backlash will be fierce — and political. Social media offers a megaphone that buggy drivers in the 1880s or steel workers a century later could scarcely have dreamed of.

What’s more, AI threatens folks who are already in positions of relative power in many wealthy nations. Imagine an “Occupy Wall Street” style movement against AI led by, well, Wall Street itself.

The political ramifications will be significant. Consider the ways in which Donald Trump’s historic 2016 campaign weaponized the resentment of people who felt left behind by outsourcing and automation.

Displacement by AI will create similar grievances that policymakers will either have to head off through accelerated job retraining or redress through expanded social safety nets for those left behind. Who will AI’s victims vote for in the future?

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Global Wealth Investments

Citi Global Wealth InvestmentsJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

The Graphic Truth

Riley Callanan

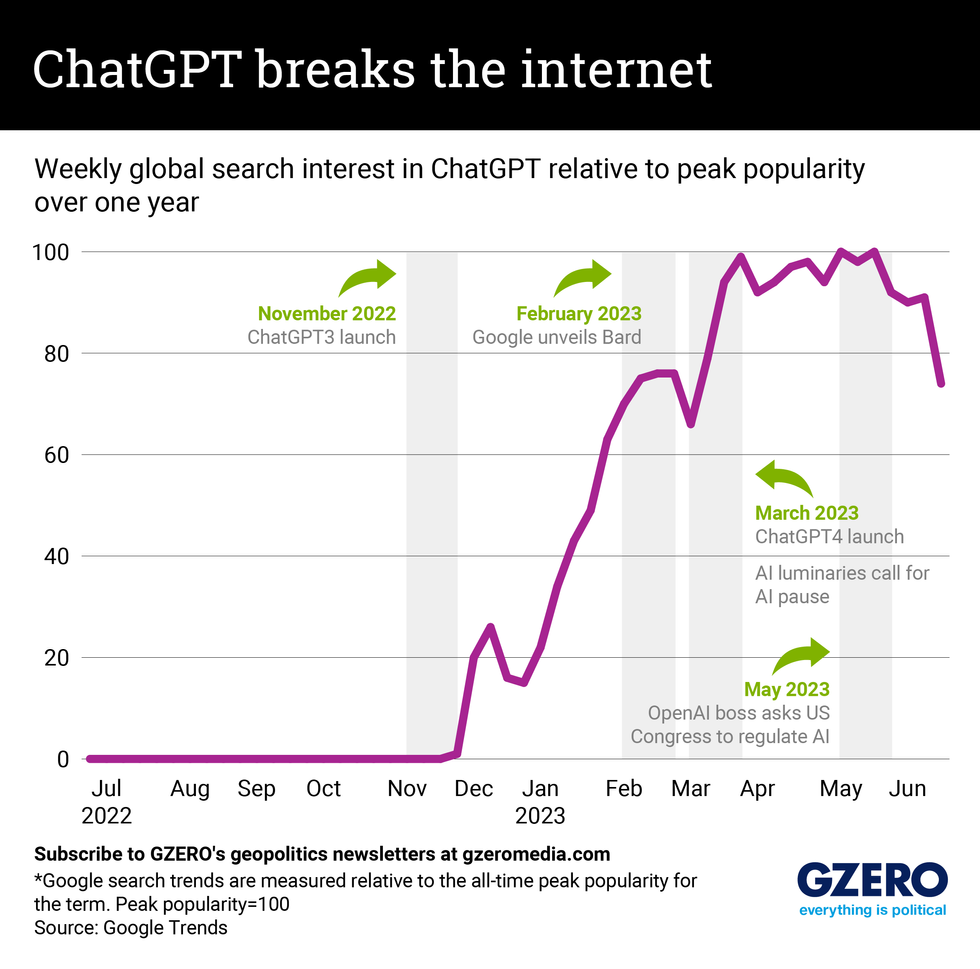

Riley CallananSince ChatGPT, OpenAI's artificial intelligence chatbot, burst onto the scene late last year, AI seems to be everywhere – so much so that it’s become an integral part of our conversations, business dealings, academics, campaign ads, and everything in between.

While being faced with constant reminders of AI’s looming threat or promise, most people still had some catching up to do on what the technology even was — let alone what it could be. And whether you are inspired, afraid, or confused about the future of AI, you probably augmented that train of thought with a trip to Google.

We took a look at Google search history to see how often the most popular AI product, ChatGPT, is crossing humanity’s minds.

Hard Numbers: SoftBank on offense, publishers want their dues, global economic boom, China’s black market

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle Debinski6.85 billion: After laying low in recent months, SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son said this week that he’s ready to move the company into “offense mode” amid the artificial intelligence boom. The company had been in a defensive posture after its investment arm incurred heavy losses worth $6.85 billion in the year ending March 31. SoftBank’s stock rose after the announcement.

20 million: Big Tech companies at the forefront of artificial intelligence developments – including Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI – are in talks with major global news publications to iron out a financial model for publishers to get reimbursed for news content used to train AI tech. Creating a workable framework for this unparalleled tech will be very difficult, with reports that some publishers have floated payouts of up to $20 million a year.

4.4 trillion: Generative AI could add $4.4 trillion to the global economy annually by reducing redundancies in work processes, according to a new report by McKinsey, one of the few firms to have assessed the long-term financial impact of AI. But there’s a catch: The report also says that 50% of work will be automated between 2030 and 2060 – 15 years earlier than the firm initially predicted.

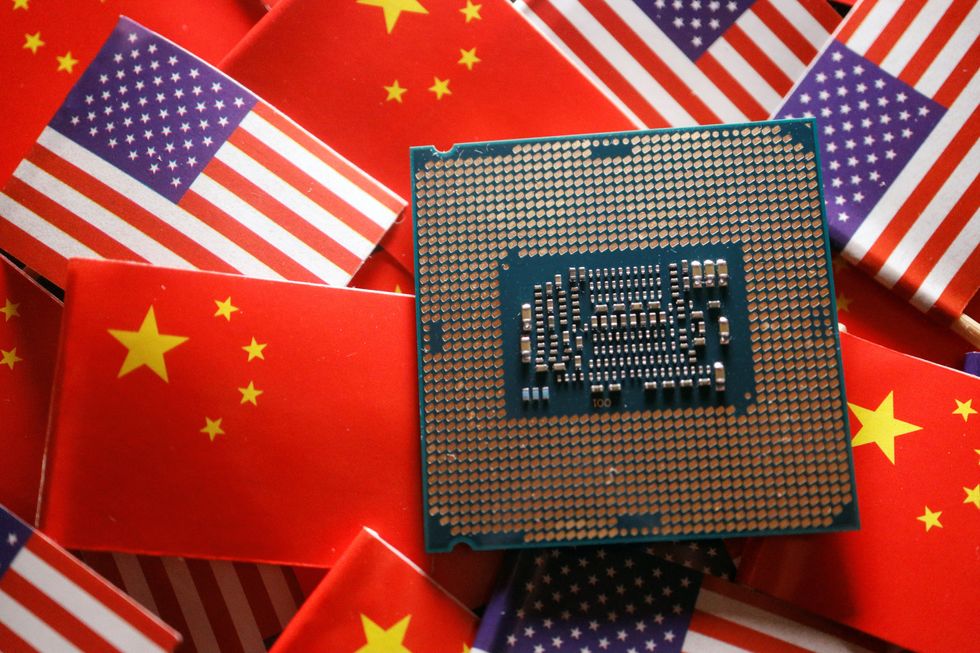

20,000: A lucrative black market for sophisticated US-made AI chips has developed in China in recent months after Washington banned US conglomerate Nvidia from exporting two of its chips, the most sophisticated in the industry, to mainland China and Hong Kong. Chips are now being sold for close to $20,000 a piece, twice the normal price. The US, for its part, has slapped a range of sanctions on China in a bid to stymie its AI and quantum computing development.How AI is changing our economy

GZERO Staff

GZERO StaffIn the latest episode of Living Beyond Borders, a podcast produced in partnership between GZERO and Citi Global Wealth Investments, we go beyond the hype surrounding generative AI and ChatGPT.

Archie Foster, managing director and head of Thematic Equities at Citi Investment Management, joins Eurasia Group’s Dev Saxena to break down how AI is transforming the economy and our political systems … and what that means for you.

Now, time for something crazy

How good is AI at generating things that are actually useful vs. terrifying vs. merely ridiculous? Can it bring our wildest imaginations to life? Or does it mutilate them in the process? You be the judge.

We asked DALL-E, an AI digital image generator, to create the image above based on this prompt: “An older rat in a top hat and monocle speaks to a young rat wearing a backpack as they stand in a post-apocalyptic New York City that has been destroyed.”

What are they saying to each other? Obviously that “the humans really did a number on themselves with that AI. On the bright side, we finally rule the planet. That’s right, even Alberta.”

This edition of GZERO Daily was written by Riley Callanan, Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. Edited by Tracy Moran. Graphic by Paige Fusco, art by Ari Winkleman.

Things are a bit frosty between the US and China these days. Whether it’s over who’s winning the tech race, trade, Ukraine, or near mid-air military collisions, the frayed bilateral ties are fueling speculation of a US-China Cold War.

But in this special edition of GZERO Daily, in partnership with Citi Global Wealth Investments, we dispute that notion while also exploring various aspects of conflict and potential confrontation, including:

- The risk of a hot war over Taiwan

- China’s global trade patterns

- The impact on allies

- War games

- Plus: Listen up for where the US and China might find common ground.

Thanks for reading.

– The GZERO Daily team

The US-China Cold War fallacy?

Willis Sparks

Willis SparksA steady stream of headlines today suggests that a metastasizing confrontation between China and the United States has put an end to what we’ve known as globalization, the flow of goods, services, and money across international borders at unprecedented speed and scale. We challenge that view.

It’s true that US-China relations have become more contentious than at any time since (at least) the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, and every time it appears things might improve, some new revelation or provocation has officials in Washington and Beijing threatening some new action. High tariffs between the two countries for all kinds of goods have remained in place for the past five years.

It’s also true that the US and China are fragmenting the flow of the globalized economy by remaking supply chains to reduce dependence on the other side for critical resources and products where they believe a shortage might threaten their national security. Yes, competition in the tech sector, especially for products like computer chips, has created an increasingly disruptive rivalry.

We also cannot ignore the reality that China’s President Xi Jinping has expressed some limited support for Russia and its president at a time when Russian forces occupy territory inside NATO-backed Ukraine and are killing Ukrainian civilians.

Washington and Beijing clearly have an increasingly contentious relationship that’s getting worse, and the globalization we’ve known over the past three decades is fragmenting in some ways.

And yet … did you know that US-China trade volumes set a record in 2022?

In the 10-plus years that Xi has ruled in China, the share of China’s exports headed for the United States, Europe, and Japan has barely moved at all. Whatever sympathy Xi has for Putin, he appears to believe that economic growth is crucial to the future of China – and its ruling party – and that economic growth depends on pragmatic relations with America and its most prosperous allies.

It’s crucial too that other wealthy countries continue to see the necessity of strong economic relations with China. US-friendly democracies in Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Canada remain closely aligned with Washington on security questions, but none of their leaders have taken action that suggests they believe China can be economically isolated as Russia has been.

In short, there is recognition in the United States, China, Europe, India, and every country that profits from a globalized economy that no one can afford a 20th-century-style division of the world into two blocs separated by a wall made hastily from cheap East German cement. Globalization may retreat for now into a surging number of regional trade deals, as we’ve seen over the past 15 years, but it has become too big to fail, and those in positions of power know the headlines don’t tell the full story.

That’s our assertion, but we’re also watching areas of the US-China conflict – and potential confrontation – that are genuinely disruptive. Have a look below and tell us what YOU think. Write to us here.

What We’re Watching: US-China tech race, fence-sitting friends, tensions over Taiwan

US-China tech “Cold War” is on

The best fallacies stem from kernels of truth. In the case of what is being framed by some as the US-China “Cold War,” that kernel lies in the tech sector, where competition between the world’s two largest economies is fierce. The Biden administration has been increasingly clear that it is intent on slowing down China’s technological rise, and has centered its efforts toward decoupling — a low-grade form of economic warfare.

The rivalry has been bubbling for years, as US national security officials worried that Chinese tech firms were stealing intellectual property from American companies and data from US citizens. It spans from crucial sectors like software and semiconductors, where the US is fighting to maintain its competitive advantage, to industries like electric vehicles, smartphones, and drones, where China has the edge (maybe AI too).

China’s technological rise can be attributed to its skilled and lower-cost workforce and its ability to subsidize domestic companies and push out Western rivals. As a result, Chinese companies lead the world in smartphone sales, especially in Asia and Africa, and Huawei dominates the (non-Western) telecommunications sector.

Alarmed by the mounting competition, the Biden administration’s decoupling strategy has taken the form of tariffs, export controls, investment blocks, and visa limits. It has also put pressure on its allies to ban Huawei from the 5G networks. Washington has dramatically expanded its control over tech flowing to Beijing and imposed aggressive sanctions on China’s chip and semiconductor industry.

Yet, the costs of decoupling may outweigh the gains. It won’t cripple China’s tech sector, but merely “slows down China at the cost of hurting US companies at the same time,” says Eurasia Group expert Xiaomeng Lu.

One way the US-China tech race could acquire Cold War vibes is by creating a bipolar world where Chinese technology reigns supreme in Asian and African nations but is blocked from the West. The US weighing a TikTok ban is a step in this direction, and US tech giants like Twitter, Google, and Facebook are already unavailable in China.

What’s more, social media is likely only the first step of the US-China decoupling. In 2020, the State Department launched a plan to block out any connection to China, including telecommunications networks, mobile apps, cloud services, and even the undersea cables that carry web data between nations.

Most of the world prefers not to choose

As the US-China rivalry deepens, many countries – including close US allies – have made it clear that they don’t want to be forced to choose between the world’s two largest economies. They are engaging in an increasingly delicate dance to try and maintain constructive relations with both.

This tricky balancing act has been particularly hard for European heavyweights, like Germany and France, that share values and many interests with Washington, but also benefit greatly from economic integration with China.

While France’s Emmanuel Macron has taken a more combative approach, saying recently that it would be “a trap for Europe” to get embroiled in crises “that aren’t ours,” German Chancellor Olaf Scholz vigorously defended a recent trip to Beijing with a host of German business leaders, writing that “we don’t want to decouple from China.” (It’s no wonder that Berlin won't roll over on this issue considering that German exports to China have tripled since 2000.)

And what about countries in the Global South that are being wooed by both the US and China? Many countries across South America, Africa, and Central and South Asia benefit from loans and infrastructure investment under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative but also rely on the US for security guarantees and aid. Since Beijing expanded its Belt and Road Initiative to Latin America in 2017, the US has tried to warn that it is a Trojan Horse aimed at increasing China’s regional clout, but Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, and others have still tried to play both sides.

For now, this approach seems to be working, but if tensions over Taiwan ratchet up, it could get harder for US allies to continue fence-sitting.

US vs. China in Taiwan

The US and China may not be in a Cold War — but they could end up fighting a hot war over Taiwan.

For many, the question is not if but when Xi Jinping will decide to invade the self-ruled island. Maybe 2025, especially if a pro-independence candidate wins Taiwan's presidential election next year and the US president is distracted by messy domestic politics. Another option is 2027, when Xi has told the Chinese military to be ready to attack. Or perhaps he will just kick the can down the road until his final deadline, 2049, when the People’s Republic turns 100.

Regardless, annexing Taiwan by force would be a huge gamble for China.

For one thing, Xi knows that no matter how much China boosts defense spending, its military has not been tested in combat since 1979, when it — checks notes — lost a border war with Vietnam. For another, China's leader is probably having second thoughts after the Western response to Russia's war in Ukraine.

What's more, the US is treaty-bound, under the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act, to help Taiwan defend itself. (Not defend Taiwan, whatever President Biden says.) But getting weapons to Taiwan under China's nose will risk direct conflict with US forces, potentially triggering World War III.

Finally, if you think the war in Ukraine did a number on the global economy, a US-China fight over Taiwan would be much worse. The island is a chipmaking superpower, and the potential hit to global supply chains is uncharted territory.CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Global Wealth Investments

Citi Global Wealth InvestmentsJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

The Graphic Truth

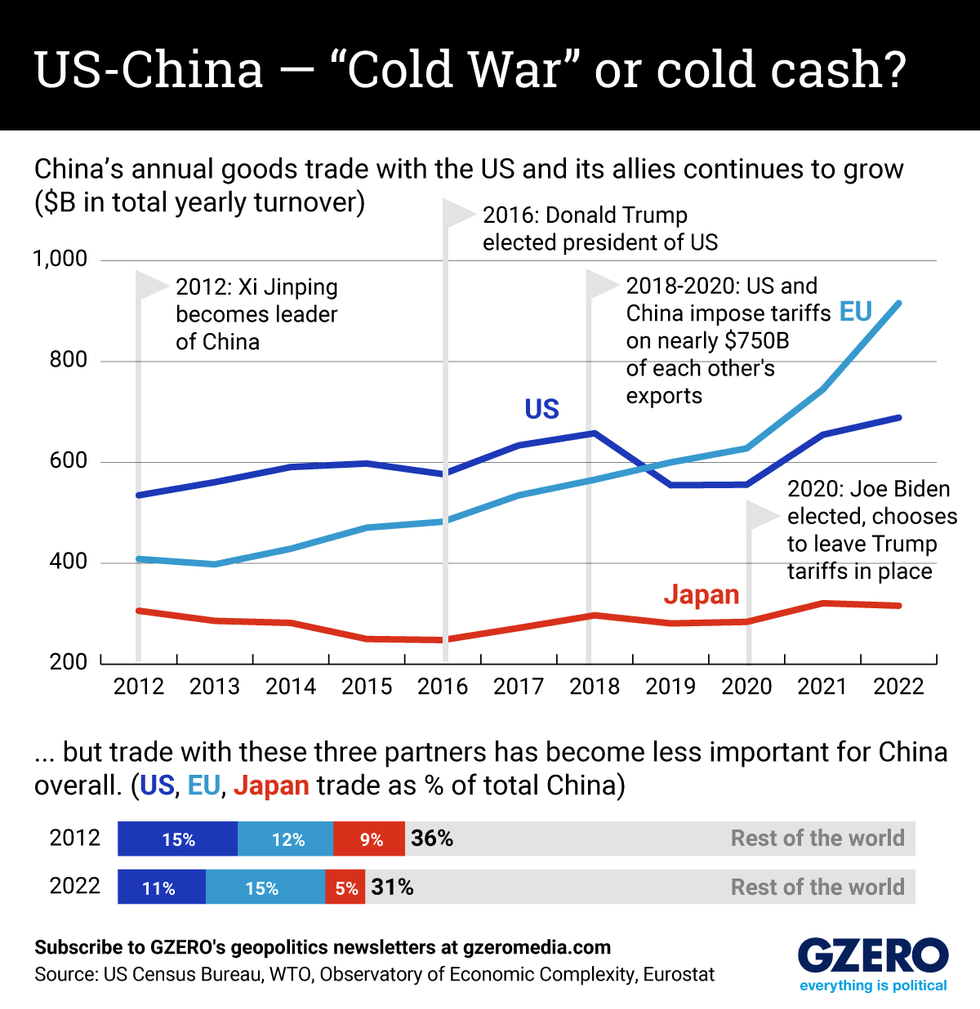

Whether the US and China are in fact slouching towards a new “Cold War” or not, one thing is certain: Commerce between them is still hotter than ever.

In the 10 years since Xi Jinping took power as China’s leader, trade volumes between the world’s top two economies have continued to grow. The same is true of Chinese trade with key US allies like the EU and, to a lesser extent, Japan.

In fact, US-China trade has continued to rise despite the Great US-China Trade War of 2018-2020, when the Trump administration and Beijing slapped tariffs on some $730 billion of each other’s goods. In 2022, US-China trade reached a dizzying record high of $689 billion. For comparison with the actual Cold War — US-Soviet trade throughout the entire 1980s amounted to less than $50 billion.

That said, while overall trade continues to rise between China on one side and the US and its allies on the other, this trade is steadily becoming less important as a part of China’s overall global commerce. That is, China is relying ever more on trade with the rest of the world, and less on Uncle Sam and friends.

To show what that looks like, we track China’s trade with the US, EU, and Japan, and look at how that has figured into China’s total trade between 2012 and now.

A Cold War may come one day, but for now, cold cash is still king.

Hard Numbers: South China Sea war games, Chinese sour on America, US chipmaking labor shortage, Ya Ya breaks the internet

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos Santamaria24: In a recent war game run by Chinese military planners, 24 hypersonic anti-ship missiles were able to sink the USS Gerald R. Ford, the US Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, every single time in 20 simulated battles. In the exercise, the US fleet is attacked after ignoring Chinese warnings not to approach a China-claimed island in the disputed South China Sea.

70,000-90,000: The US CHIPS Act is pouring billions of dollars into bringing semiconductor factories back to American soil to counter China. But, who will make the chips? According to one estimate, the US chipmaking industry faces a shortage of between 70,000 and 90,000 workers (engineers and technicians) in the coming years.

12.2: Only 12.2% of Chinese people “like” the United States, according to a new survey about views on national security by Tsinghua University, Xi Jinping's alma mater. The most popular country is Russia (54.8%) and the least, India (8%).

230 million: China's superstar giant panda Ya Ya finally returned to Beijing this week after 20 years at the Memphis Zoo in the US. Ya Ya, whose troubled journey encapsulates the current state of US-China ties, has become such an internet sensation among patriotic Chinese that a hashtag following her homecoming got 230 million views on Weibo, China's answer to Twitter.Listen up: Can the US and China find common ground?

In this episode of Living Beyond Borders, a podcast produced in partnership between GZERO Media and Citi Global Wealth Investments, we bring you the expert take on US-China relations.

With competing motivations, the superpowers are looking to protect themselves from each other … but they’re also intertwined. David Bailin, chief investment officer at Citi Global Wealth, and Eurasia Group and GZERO President Ian Bremmer unpack the delicate US-China balancing act.

This edition of GZERO Daily was written by Riley Callanan, Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. Art by Annie Gugliotta, graphic by Ari Winkleman. Edited by Tracy Moran.

In this special edition of GZERO Daily, in partnership with Citi Global Wealth Investments, we focus on all things inflation … including:

- Ways to address it

- Those who embrace it

- Nigeria’s eye-popping food prices

- Historical recessions

- Dinosaur skeletons

Thanks for reading.

– The GZERO Daily team

What We’re Watching: Three ways to address inflation … with varying degrees of success

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiErdonomics: Growth > stability

Turkey has long had a hyperinflation problem, but that doesn’t mean that its central bank has sought to raise interest rates to bring prices down. In fact, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose unorthodox economic approach has been dubbed Erdonomics, has even sought to lower interest rates during inflationary times. Why?

Central to his approach is the belief that economic growth trumps all, including price stability. So Turkey’s central bank has been unwilling to raise interest rates to reverse hyperinflation, and Erdogan has even called himself an “enemy” of interest rates.

As the Turkish president explains it, keeping interest rates low – and static – stimulates demand, driving economic growth.

But that hasn’t panned out. Inflation in Turkey soared to a quarter-century high of 85% in October – largely due to roaring food and fuel prices. Crucially, analysts think the official number was closer to 186%, meaning prices would have almost tripled. As a result, the average Turk has far less disposable cash to inject into the economy. What’s more, Turkey has seen its currency, the lira, plummet a whopping 90% since 2008.

What do Turks think of the cost-of-living crunch? They will get to weigh in on May 14, when the country heads to the polls. Erdogan is facing a united opposition that has been pushing the message that he has wrecked the economy.

Price controls and unintended consequences

Inflation = prices going up. But what if they just … didn’t?

That’s basically the thought process behind price controls, an alternative tactic for fighting inflation where the government mandates maximum prices for goods. While this might sound good, price controls remove the magical balance of supply and demand: When something is expensive, it signals to producers that they can profit by increasing supply. But if the government artificially holds down prices, producers aren’t incentivized to meet demand, which leads to supply shortages, inefficiencies, and unintended consequences.

Most economists believe that monetary policies can tame inflation without capping prices. But with inflation now running rampant, some left-wing policymakers and economists are revisiting the idea. In 2022, US Sen. Elizabeth Warren proposed a bill to outlaw “abusive price gauging” during market shocks. Progressives argue that price caps help the poor, but there’s a catch.

The thing about price controls is that they tend to work in the beginning. In 1971, President Richard Nixon tried to nip inflation in the bud by implementing a 90-day freeze on most wages, prices, and rents. The result: Inflation fell by 50% ... at first. But as soon as the government eased restrictions, prices shot back up, requiring another round of caps that barely made a dent. The takeaway: Price controls might help in the short run, but not in the long run.

Argentina has long been addicted to using price controls for political gain. In late 2021, after an electoral loss attributed to 53% inflation, the ruling party slapped price controls on over 1,400 products. But like the last time the government did this in 2013, it’s only making inflation worse — currently over 100% year-on-year.

The historical upshot of price controls: When the precise balance of supply and demand is replaced by the blunt axe of government policy, the solution is more likely than not to be worse than the problem.

The Goldilocks approach to adjusting interest rates

Western central banks are, broadly speaking, focused on two key things: Keeping inflation down and employment up. To strike the right balance, and, like Goldilocks, ensure that the economy is neither too hot nor too cold, many central banks adjust interest rates to prevent the economy from overheating.

Given the inflationary pressures of the past year – as a result of the war in Ukraine, supply chain kinks, and pandemic stimulus – the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, Bank of Canada, and others, have aggressively raised interest rates to increase the cost of credit within their respective economies.

While interest-rate policy aims to keep consumer prices steady (global food prices, in particular, have soared), central banks’ policies also influence – and are influenced by – financial behaviors.

For example, market turmoil in the US in recent times has tampered with investors’ appetite for risk. This has partly contributed to mass layoffs in the tech sector, something the Fed is watching closely as it adapts its interest-rate policy.

But not all wealthy countries are adopting this approach. For instance, the Bank of Japan, which has long focused on keeping interest rates low to stimulate growth, has left interest rates at - 0.1%, leading to stubbornly high prices for consumers.

__________________________________

Not everyone hates inflation – just ask the dinosaur skeletons

Rising prices are a headache for most people, but not everyone is unhappy. People who have low fixed-rate mortgages or other fixed-cost debts, for example, actually get a break from inflation, because it has the effect of reducing the burden of repaying or servicing what they’ve borrowed. Paying what they owe costs less because the currency has lost value compared to when they took out the mortgage.

Meanwhile, there are folks who hold assets that tend to rise in value when inflation goes up, such as stocks in energy or food production companies. Another is gold, which generally rises in value during bouts of inflation because it’s seen as a more stable store of value — after all, it’s been used as money for 2,500 years.

But the most colorful beneficiaries of inflation may be hoarders or other collectors of items like Rolex watches, fine art, classic cars, designer handbags, sports memorabilia, fine wines, and even dinosaur skeletons!

As inflation drives down the value of money, people invest in items like these, which are seen to hold value more predictably than cash. Not everyone has access to a fine wine cellar or a classic car garage, but surely you’ve got an unexpected inflation hedge lurking in some old shoebox somewhere, don’t you?

Tell us what you collect/hoard for rainy days here.

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Global Wealth Investments

Citi Global Wealth InvestmentsJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

The Graphic Truth

Carlos Santamaria

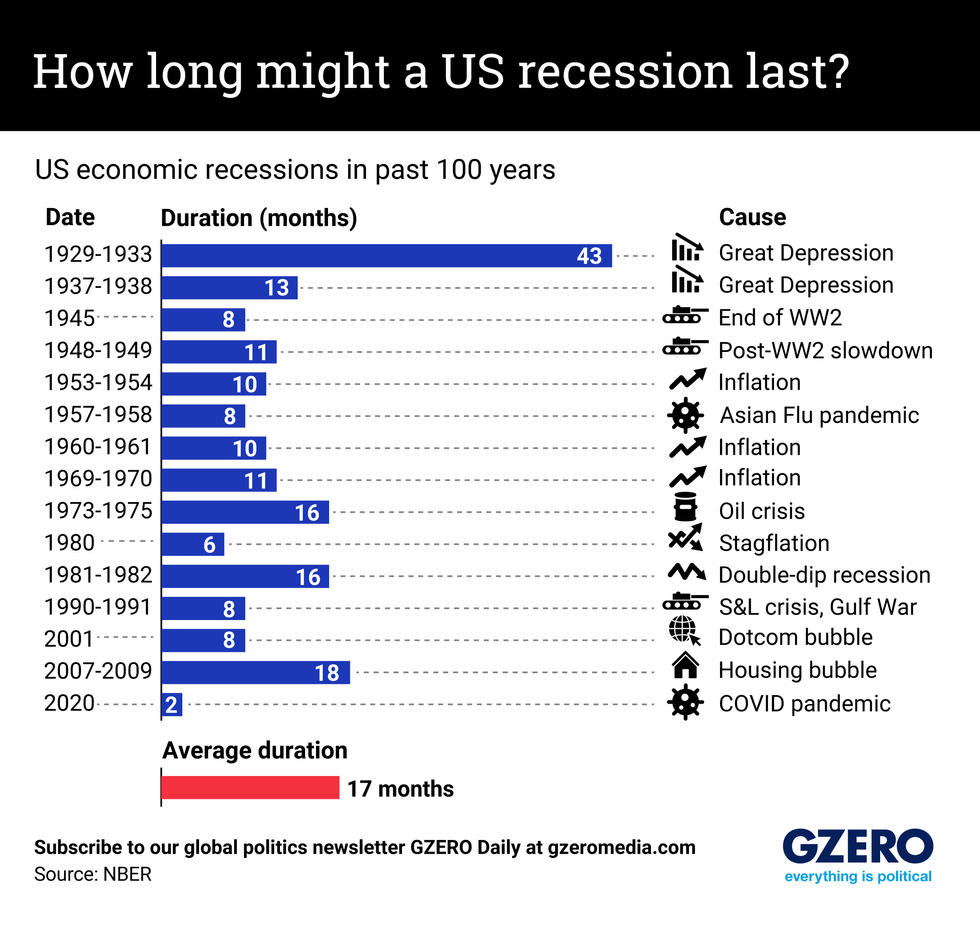

Carlos SantamariaFor months, we've been debating the odds of a looming inflation-fueled US recession. It hasn't happened yet — in no small part due to a tight jobs market. (For more on who makes the recession call, read our primer here.)

But the fact that it hasn't happened yet doesn't mean recession fears are over. In fact, economists believe it'll start as soon as cash-strapped businesses — faced with high interest rates to fight inflation — begin giving workers pink slips across the board. Still, it's more likely than not that when it comes, the recession will be not only mild (not triggering mass unemployment) but also historically short.

We take a look at the duration and cause of US recessions over the past century.

Staving off default: How unsustainable debt is threatening human progress

At last week’s World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings, GZERO Media spoke with Navid Hanif, assistant secretary-general for economic development at the UN, about the fact that three-fifths of the lowest-income countries in the world are debt distressed and in danger of default.

Hanif explains how a financial divide will eventually become a development divide, which is not good for the world. While stressing the urgency of the growing debt problem, Hanif also expresses optimism about the potential for post-pandemic progress, citing the growth of internet access and a renewed commitment to climate goals.

Hard Numbers: World inflation champs, hyperinflation history, device deflation, how much do you spend on food?

Alex Kliment

Alex Kliment538: What country currently has the highest annual inflation rate in the world? Crisis-wracked Lebanon (190%) is up there, and so too are the perpetually mismanaged economies of Argentina (103%) and Zimbabwe (92%). But at the moment, independent economists say Venezuela’s annualized price growth is running at a dizzying 538%. A combination of overspending and a plummeting currency is to blame.

143: You’ve probably heard about the quadrillion percent inflation that took hold in post-World War II Hungary, an episode generally regarded as the worst example of hyperinflation in modern history. But the one that started it all was in France more than 150 years earlier, when in the months after the French Revolution, inflation hit 143%. Let them eat cake, indeed.

24: Is anything getting cheaper these days? Yes! It’s in your hand/pocket/purse! According to the latest US Consumer Price Index report, which tracked prices through February, the item that has shown the biggest price drop is … smartphones, which cost 24% less than a year ago.

59: How much does food price inflation hurt? In Nigeria, households spend an average of 59% of their income just on eating. The figure for most emerging and developing economies is above 25%, while among the wealthiest G7 economies, it’s closer to 15% or less. In the US, an average household spends just below 7% of its income on food.Podcast: Recession or not?

GZERO Staff

GZERO StaffIn the latest episode of Living Beyond Borders, a podcast produced in partnership between GZERO Media and Citi Global Wealth Investments, Eurasia Group’s Rob Kahn has a frank discussion with Charlie Reinhard, head of Citi’s Investment Strategy for North America, about the state of the economy and unemployment. They dive into the sticky rates of inflation, what the Federal Reserve is going to do about it, and what kind of recession – if any – investors should expect.

This special edition of GZERO Daily was written by Riley Callanan, Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, and Carlos Santamaria. It was edited by Tracy Moran. Graphic by Luisa Vieira, art by Annie Gugliotta.

In this special edition of GZERO Daily, in partnership with Citi Global Wealth Investments, we focus on the uncertainty stalking the global economy.

Today we’ve got:

- Three geopolitics stories that could boost/burn the global economic recovery

- A white-knuckle ride to renewing the Ukraine grain deal

- Growing tech layoffs (even before Friday’s SVB blowup)

- An unexpected link between Xi Jinping and Kurt Cobain?

Thanks for reading.

The GZERO Daily team

What geopolitics stories could still blow up the global economy?

Investors hate uncertainty. For now, most of them are trying to understand how central bankers, particularly at the US Federal Reserve, will calibrate changes in interest rates to slow inflation while avoiding recession.

But there are also three big geopolitical stories that will generate plenty more questions throughout 2023.

Russia’s war

After more than a year of war following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, two realities have emerged. Russia’s military isn’t strong enough to conquer Ukraine, but it is probably strong enough to prevent a complete Ukrainian victory. The war has now settled into a stalemate that continues to put upward pressure on energy prices and threaten further surges in food prices. (The current deal to allow grain exports through the Black Sea expires on March 18.)

To some extent, the consensus expectation for a war that lasts beyond 2023 will allow producers and companies to adjust their supply chains to new realities, to make alternative arrangements for diminished supplies of oil, gas, grain, and other commodities, and to find new trade partners.

But wars create surprises, and Russia’s inability to win the war leaves its leaders to think up creative new ways to punish Ukraine and its backers, with attacks in cyberspace, on pipelines, or on fiber optic cables, for example, adding wildcards to a deck already stacked against a predictable economic recovery from COVID.

China’s rebound?

In a time of war and global economic uncertainty, China poses a long list of questions. After all its extended COVID lockdowns, can Chinese leaders jumpstart China’s own economic growth to inject new fuel into global commerce? The relatively modest growth target the Chinese leadership recently announced generates optimism that Beijing has a realistic understanding of the risks in pushing too hard too quickly on state spending and loose lending. Has China finally cleared its COVID hurdles? There’s a lot of optimism on that front. Will US-China relations continue to deteriorate? If Washington decides that Xi Jinping’s government is trying to boost Russia’s odds of winning the war, that’s a safe bet.

Iran in flux

Two weeks ago, a senior US Defense Department official issued a startling warning. “Back in 2018,” he said, “when the [Trump] administration decided to leave the JCPOA, it would have taken Iran about 12 months to produce one bomb's worth of fissile material. Now it would take about 12 days.” That followed news in February that the International Atomic Energy Agency charged with monitoring Iranian nuclear facilities had reported finding small quantities of uranium enriched at 84%. (Enrichment at 90% can produce a nuclear weapon.)

This is a country preparing for its first transition of supreme leadership in more than 30 years, given Ali Khamenei’s advancing age and declining health. (He’ll be 84 next month.) It has faced widespread protests. The unrest seems to have died down for the moment, but given how abruptly the upheaval began, some new and equally unexpected trigger could start the cycle of demonstrations all over again. And Iran’s willingness to provide Russia with drones for use against Ukraine has newly antagonized Europeans as well as Americans.

There are fears in Israel that only an attack on Iran can prevent the development of a nuclear weapon. What’s more, many say that the recent restoration of ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, brokered by China, is yet another sign of the deepening rift between Washington and Riyadh. Taken together, this all suggests there is constant wrangling in the heart of the world's main oil-producing region, where the US holds limited leverage.

In all these cases – Russia’s war, China’s rebound, and Iran’s flux – we have risks that are reasonably well understood. None is guaranteed to create a new and unforeseen crisis, but all of them bear careful watch through 2023 and beyond.

What We’re Watching: Grain deal deadline, tech layoffs, interest rate ripples

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiWill the Black Sea grain deal be renewed?

Amid growing concern that Russia may refuse to renew a deal to allow food and fertilizer shipments to travel through a safe passage in the Black Sea, UN Secretary-General António Guterres this week visited Kyiv, where he called for the renewal of the agreement, which is set to lapse on March 18. Quick recap: The grain deal, negotiated by Turkey, the UN, Russia, and Ukraine, was implemented in the summer of 2022 in a bid to free up 20 million tons of grain stuck at Ukrainian ports due to Russia’s blockade. You’ll likely remember that the two states are both huge exporters of wheat, while Russia is also the global fertilizer king. Indeed, the deal has helped alleviate a global food crisis that was hitting import-reliant Africa particularly hard, and driving up global food prices. Kyiv, for its part, says that if the deal is expanded to additional ports it could export at least some of the 30 million tons of grain that remain stuck. The Kremlin hasn’t said what its plans are but this week accused the West of “shamelessly burying" the Black Sea deal in what could be used as a pretext for its refusal to play ball.

For more on what Guterres has to say about the ongoing war in Ukraine and its human toll, check out his interview with Ian Bremmer on GZERO World.

What should we make of the great tech implosion?

We’ve heard a lot about a downturn in the tech sector in recent months after giants including Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, Salesforce, Alphabet, and Spotify laid off large chunks of their workforces. All in all, an estimated 200,000 US tech workers have been shown the door since the start of 2022 – more than the equivalent of the entire Apple workforce. At the same time, however, unemployment in the US remains at record lows, with the US adding more than 311,000 new jobs in February alone, yet another sign of the labor market's resilience. So what does – and doesn’t – the great tech debacle tell us about the current state of the global economy? First, COVID was a boon for the tech sector. As the world shut down, tech companies made the most of increased demand for work/play/eat-from-home services and embarked on massive hiring sprees. Alphabet, for example, increased its workforce by 16% between 2020-2021. But as soon as things reopened, it became clear that consumers wanted to go back to exercising in sweaty gyms and dining at overpriced ramen bars. Demand plummeted. What’s more, rising interest rates – an effort to tackle runaway inflation – and a dizzying stock market are making it harder for tech companies to raise capital and putting downward pressure on stock prices, leading to massive cost-cutting measures. Crucially, analysts warn that things will get worse before they get better.

A mountain of interest rate-driven debt

In the same way that inflation is a global problem, the fix has worldwide ripple effects. Indeed, rising interest rates to tame inflation are making it more expensive to borrow money — as well as pay it back. Last year, a group of 58 developed and emerging economies accounting for over 90% of global GDP surveyed by The Economist were on the hook for a whopping $13 trillion just in interest payments on their debt, up an astounding 25% from 2021. And this is on top of all the additional money that many countries borrowed to spend on stimulus programs during the pandemic. Everyone now owes a lot more than they signed up for at the micro and macro levels: Mortgage rates in the US have skyrocketed, corporate debt has ballooned in Hungary, and highly indebted countries like Ghana are now in even bigger trouble. So long as inflation forces central banks to keep interest rates high, access to capital will be tight for everyone: people looking to finance homes and cars, countries seeking relief from their massive debt burdens, and companies looking to raise money. And as the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank on Friday showed, this kind of risk aversion on the part of investors can — when the stars misalign — threaten to unleash broader financial chaos.CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Global Wealth Investments

Citi Global Wealth InvestmentsJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

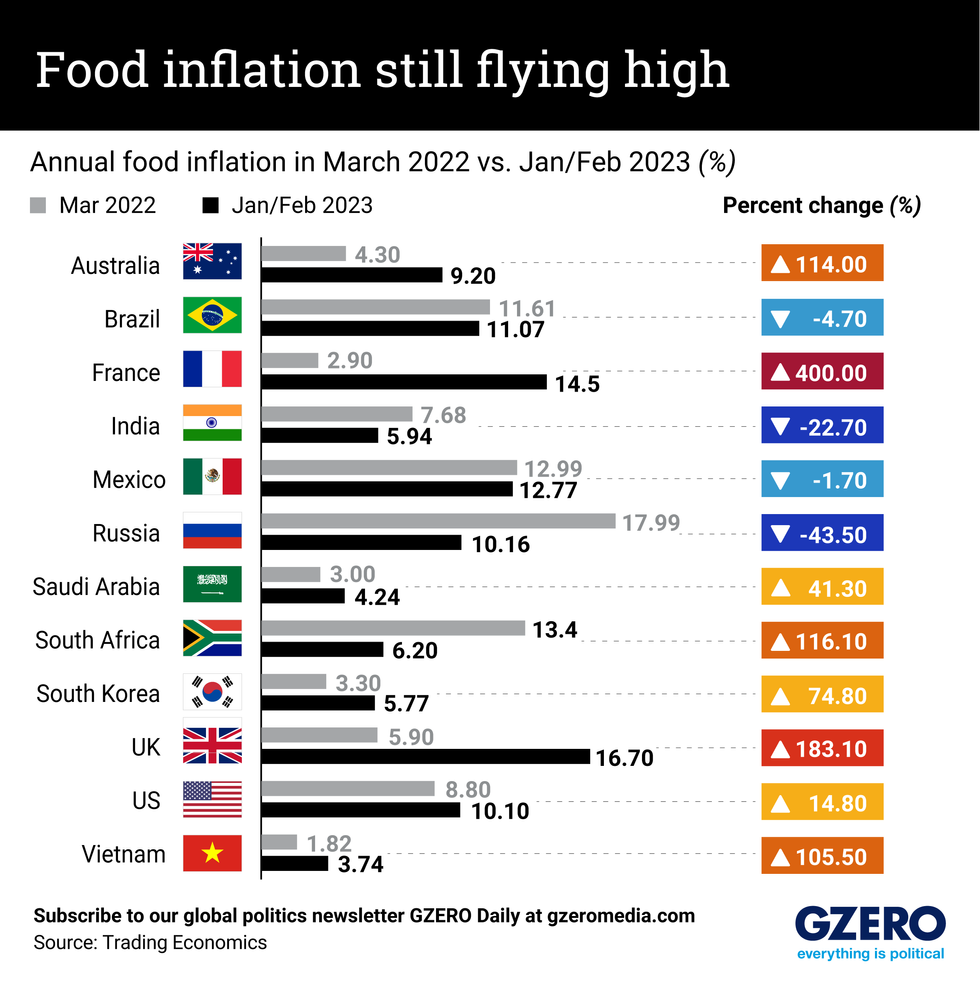

Gabrielle DebinskiAs the war in Ukraine lingers and pandemic aftershocks continue to pound the global economy, food inflation remains sky-high throughout much of the world. Consider that over the past year alone, egg prices in the US rose by a whopping 60% on average. While prices of some food staples have dropped in recent months, partly due to the Black Sea grain deal, stubborn inflation driving up transport and labor costs means that consumers aren’t feeling prices ease at the supermarket. We take a look at food inflation in select countries now compared to a year ago, exactly one month after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Hard Numbers: Beijing underpromises, Russia slips sanctions, sunlight helps to grow US jobs, oil prices in perspective

Alex Kliment

Alex Kliment32: Beijing’s new 2023 GDP growth target of “around 5%” is the country’s lowest in 32 years. The last time the Chinese Communist Party hedged this much, the Soviet Union was still around and a little-known band from Seattle had just released a record called “Nevermind.”

2.2: Despite the most comprehensive Western sanctions ever placed on its economy, Russia’s GDP shrunk just 2.2% last year, defying hopes and predictions of a much larger collapse. Why? Europe and the US were reluctant to sanction Russian energy exports too harshly, and Asian buyers were more than happy to buy up what the West wouldn’t.

126,000: Nearly a quarter of new jobs added by the US in January were a direct result of … the weather. An analysis by Morgan Stanley found that sunny skies heated up hiring in the world’s largest economy, creating an additional 126,000 jobs in the first month of the year.

40: Although oil prices have started to creep up again as China’s economy gets back to business, crude is still 40% cheaper than it was a year ago, right after Russia invaded Ukraine. Still, with China predicted to import record amounts of oil in the coming months, prices could rise more later this year.Podcast: Should I STILL be worried?

“The equivalent of what we spent in World War II was spent in the course of a year and a half to support the US economy, and that had global impacts,” says David Bailin, chief investment officer and global head of investments at Citi Global Wealth. “All of that was rolled out with incredible speed and effectiveness. And the hangover effects from that … are very, very significant,” Bailin explains on the latest episode of Living Beyond Borders, a podcast from Citi Global Wealth Investments and GZERO Media.

Bailin and Eurasia Group President Ian Bremmer, together with moderator Shari Friedman, discuss the state and future of the global economy amid the war in Ukraine. While 2023 will see slow growth, Bailin says, this resetting period will lead to significant opportunities for global growth in 2024 and beyond.

Want to know how worried you should be about the state of the economy? Tune in here.This edition of GZERO Daily was written by Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. Graphic by Luisa Vieira, art by Paige Fusco. It was edited by Tracy Moran.

In recent years global supply chains have gotten badly kinked by resurgent protectionism, the economic havoc of the pandemic, deepening rifts between the US and authoritarian countries, and the war in Ukraine. The result is inflation levels not seen in advanced economies since the 1980s and a food security crisis of global proportions.

In this special edition of Signal, we’ll ask what comes next by surveying the scarcities, tracking the travails of truckers, scarfing down a handful of (micro)chips, and asking whether “friends” can really save the day. Enjoy!

- The Signal Team

Can you get by with a little help from your friends?

Alex Kliment

Alex KlimentThe pandemic inflicted a huge shock on supply chains, but there is another force at work remapping global trade flows too: the deepening ideological divide between the US and China, framed in Washington as a broader competition between democracies and autocracies.

The so-called “de-coupling” between the world’s two largest economies began during the presidency of Donald Trump, who slapped tariffs on China in a largely unsuccessful attempt to address the real harms that offshoring has done to some US workers.

But now, as global trade reorients itself in the wake of the pandemic, Washington is making a broader push for US companies to source their goods from factories in friendly democracies rather than authoritarian countries — China, Russia, and the gang — that could use their control over key materials or products to inflict pain on the West. Russia’s use of oil and gas to pressure Europe is one clear example, of course, but there are others: China’s monopoly on the production of rare earths used for electronics, or the precarious concentration of global microchip production in Taiwan, which lives under the constant threat of Chinese invasion.

US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently touted the benefits of so-called “friendshoring” on a visit to South Korea, which is trying to lure American supply chains away from China and to start making more microchips itself. Southeast Asian manufacturing powerhouses like Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia are also keen to continue capitalizing as “friends” of the US.

Friendshoring may offer certain protections in a world of deepening ideological competition, but there are tradeoffs: “friendly” countries may not always produce goods as cheaply or efficiently, meaning that consumers may have to accept higher prices, particularly in the short term. Is the tradeoff of greater security in exchange for less efficiency worth it? More to the point, is it now unavoidable?

Shortages reach far beyond food

Willis Sparks

Willis SparksThe war in Ukraine is just the latest crisis to befall global supply chains in recent years, and it appears likely to get worse before it finally eases. It’s not just about interrupted flows, shortages, and higher prices for food and fuel. According to a report published in May 2022 by Dun & Bradstreet, a total of at least 615,000 businesses operating globally depend on supplies from either Russia or Ukraine. About 90% of those firms are based in the United States, but supply chains in Europe, China, Canada, Australia, and Brazil are heavily impacted. According to the report, a total of 25 countries have a high dependency on Russia and Ukraine for a variety of commodities.

Five months into the war, it’s clear that the likeliest outcome of the current fighting will be a long-term stalemate. Russia doesn’t appear militarily strong enough to take and hold all of Ukraine, and Ukraine doesn’t appear strong enough to drive Russian troops completely off Ukrainian land. As a result, those who depend on resources and production inputs from Russia and Ukraine now know they’ll likely need to invest in new suppliers of hundreds of different commodities and products – from sunflower seeds to turbojets – to build better resilience into their supply chains, rather than simply waiting for the fighting to end.

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Private Bank

Citi Private BankJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30 am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

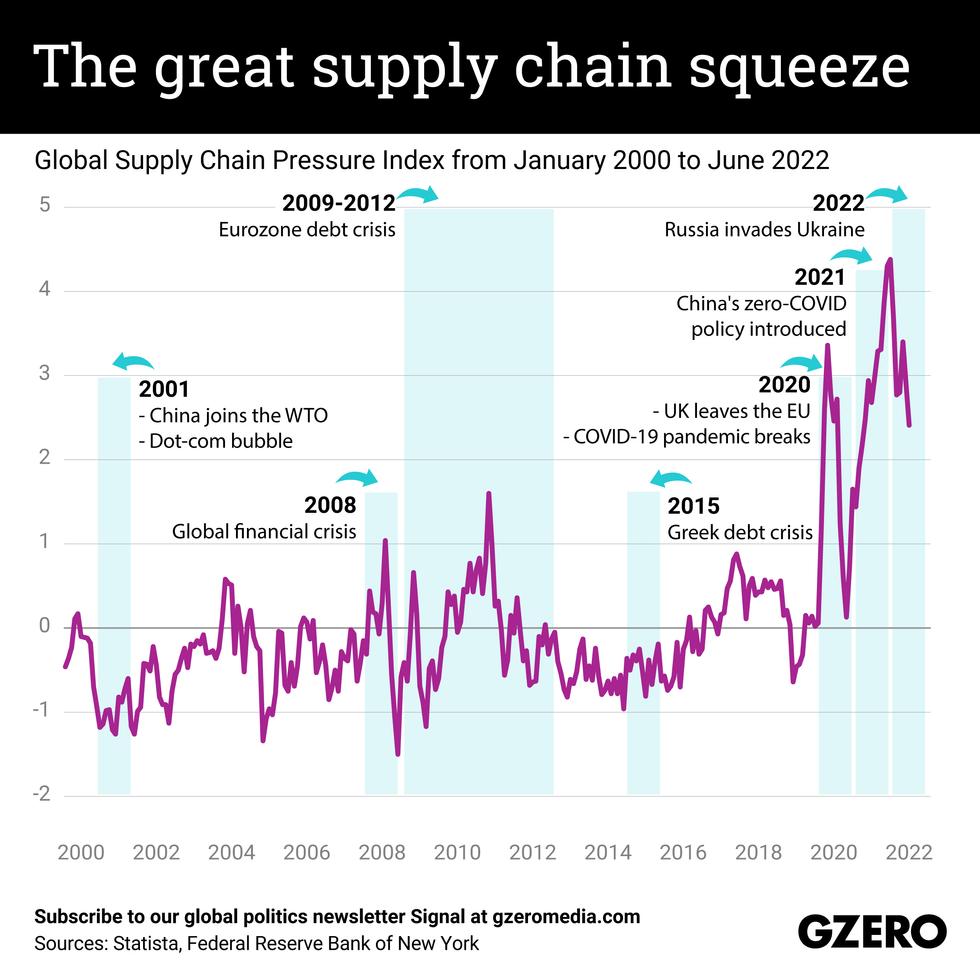

The Graphic Truth

Luisa Vieira

Luisa VieiraThe pandemic sent global supply chains into a tizzy. Then, just as economies were embarking on their post-COVID economic recoveries, Russia invaded Ukraine, upending the global grain trade and sending supply chains spiraling further. Supply chain frictions have a lot of unintended consequences: Brexit-related supply chain issues made it hard for some Brits to get their hands on a pint of beer, while China’s punitive zero-COVID policy drove the auto industry – among others – into a full-blown crisis. We take a look at the Global Supply Chain Index from 2000-2022 along with key global economic milestones.

What We're Watching: Truckers wanted & not-so-cheap chips

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiWhere are all the truck drivers?

The global truck driver shortage has been disrupting already-out-of-whack supply chains, particularly in the US, the European Union, and Britain – further complicating their post-pandemic economic recoveries. Last year, the American Truckers Association said it was around 80,000 drivers short, while in Europe, a deficit of 40,000 truckers has contributed to long waits and empty shelves. What’s going on? The pandemic has upended the way we work. Trucking is an arduous and ungratifying gig: Drivers often spend days or weeks far away from home, and they don’t get paid for hours spent waiting for goods to be loaded and unloaded. The road can be grueling, the compensation is underwhelming, and the benefits are often … nonexistent. In the US, trucking salaries have plunged in recent decades. Median wages for truck drivers in 1980 were about $110,000 annually (adjusted for inflation); in 2020, they were just $47,130. Unsurprisingly, many truckers are opting for jobs with better conditions and pay, so trucking firms in Europe and the US are struggling to lure drivers back to work and recruit new staff. It’s particularly grim in the UK, where supply-side frictions have been exacerbated by Brexit. In the US, meanwhile, companies like Walmart are fighting back by offering massive salary hikes to attract truck drivers. Will it get the wheels turning?

Chipping away at supply chains

The US Congress this week passed the behemoth Chips and Science Act, which ponies up $52 billion in subsidies and incentives to boost domestic production of semiconductors, the invisibly thin microchips that are essential for everything from phones, cars, and factories, to fighter jets, cruise missiles, and artificial intelligence. With the bill, Congress is making a big move in a new global “Chips race” for dominance of the industry: the EU is now spending close to $50 billion on the same thing, and China, which still depends on the US and its allies for inputs into its home-grown chips, has poured hundreds of billions into someday becoming a semiconductor superpower itself. For all three of the world’s largest economies, the concern is the same: the semiconductor market is highly concentrated, particularly in Taiwan, which produces more than 60% of the world’s chips. That’s a problem commercially – in 2021, there was a global shortage after tech firms gobbled up the entire supply, leaving automakers scrambling for chips. But it’s also a problem geopolitically. China doesn’t want to be dependent on chips from a Taiwan that’s allied with the US, while the US and EU don’t want to rely on a Taiwan that could be taken over by China any year now. Critics of the Chips act say its a sop to powerful tech companies that can well afford to build their own factories, and there are questions about whether the money will be spent on the right things: making the chips is one thing, cutting edge R&D is a whole other bowl of chips, and the supply chain for a single chip can pass through many countries before final assembly. As a cautionary tale: the EU aimed in 2013 to double its share of global semiconductor production to 20% by 2020. It didn’t work.

Future-proofing: How we fix broken supply chains

“Envision supply chains like a strand of Christmas lights. If one light goes out, then the whole strand will stop working.” So says Eurasia Group’s Christina Huguet on the latest episode of the Living Beyond Borders podcast, which focuses on the moments those lights went out: when the pandemic hit shipping, manufacturing, and labor all at once. Huguet, along with moderator Shari Friedman, Eurasia Group’s Managing Director of Climate and Sustainability, and David Bailin, Chief Investment Officer and Global Head of Investments at Citi Global Wealth, look at what it will take more than two years later to turn those lights back on and create more resilient global supply chains.

Listen here.

Hard Numbers: The scarcity edition

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle Debinski2 million: As the war in Ukraine rages on, the African continent is facing a shortfall of around 2 million metric tons of fertilizer that’s causing an unprecedented loss in food production throughout the continent. A Senegalese official warned at a recent G20 meeting that starvation could kill more Africans than COVID-19.

10: American women are the latest victims of the supply chain crunch. Tampon shortages as a result of staffing issues at manufacturing plants, transportation disruptions, and the scarcity of materials like cotton caused tampon prices to soar almost 10% in the US in recent months.

50: Europe’s largest paper packaging company, Smurfit Kappa, recorded a whopping 50% increase in core profit during the first half of this year as a result of surging pandemic-related demand. Still, the company says it’s preparing for paper shortages across the continent in the months ahead as a result of mandatory gas rationing as EU states try to reduce their dependence on Russian natural gas.

10: Several Polish supermarkets are limiting sugar purchases to 10 kilograms per person after consumers cleared out shelves fearing further price hikes and scarcity of the sweet staple. Poland, one of Europe’s biggest sugar producers with ample supply of the stuff, recently recorded its highest inflation rate in 25 years.This edition of Signal was written by Beatrice Catena, Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. Edited by Tracy Moran. Graphic by Luisa Vieria. Art by Paige Fusco.

In a special Sunday edition of Signal, we take stock of the geopolitical situation halfway through one of the most tumultuous years in recent memory. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine boosted Euro-Atlantic unity but deepened fault lines between the “West” and powerful emerging markets. A global food crisis still looms, and later this year we’ll see pivotal and extremely contentious elections in Brazil and the United States.

If the last six months are any indication, you’ll want to buckle up for the second half of the year.

-The Signal team

Resilience in an era of crisis

Willis Sparks

We live in an era of emergency. Since 2008, we’ve seen a global financial crisis, a sovereign debt crisis in Europe, and a wave of unrest that sparked political turmoil across North Africa and the Middle East. Civil wars in Syria and Libya helped trigger a migrant crisis that upended European politics. Then came Britain’s exit from the EU, the surprise election of a US president who upended the most basic assumptions about America’s role in the post-war world, and a political crisis in the wake of his defeat. Next came a global pandemic that has killed millions and continues to inflict human, economic, and political damage in every region of the world. Now we have Russia’s war on Ukraine, millions more refugees, and a global food emergency that has only just begun. All of that has happened in the past 14 years.

Given all that, it’s obvious that deeper investment is needed in resilience at every level of government, commerce, and society. In a world of shocks, we need good shock absorbers. Political and business leaders now face a basic choice. They can build networks of trade and political alliances with only like-minded partners – those with similar political systems, cultures, or overlapping interests – to ensure competitors and potential enemies can’t gain strategic advantages by exploiting weaknesses like monopolies on needed resources or supply-chain vulnerabilities. Or they can diversify their partnerships to build relationships where they make the most sense for economic value and the common good. It’s possible that governments will now use sanctions, tariffs, export bans, subsidies, and other forms of protectionism as everyday weapons to build resilience by enhancing security. Others will continue to seek resilience through a broader diversification of their partnerships.

This choice will be most obvious in relations between China and the West. Will the US and EU begin to treat China primarily as a political and economic opportunity or mainly as a security risk? Will China seek a more confrontational role toward the West and the international institutions where it has outsized power, or will it continue to define its security through the dynamism of its global trade and investment relationships?

These are the questions most likely to determine how well the global economy and current international system absorb the next generation of shocks.

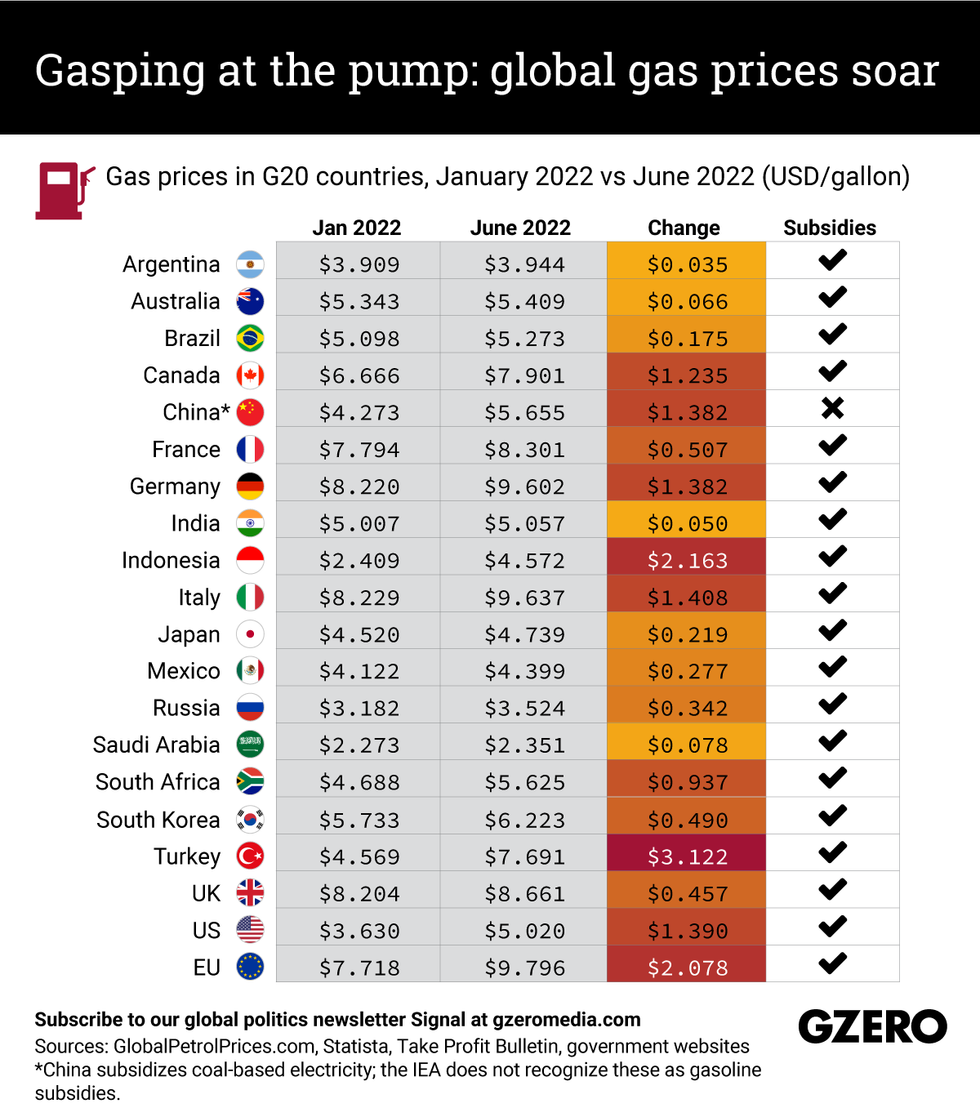

The Graphic Truth

Beatrice Catena

Beatrice CatenaPrices at the pump are soaring. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, much of the world has been affected by the economic impact of sanctions, higher inflation, constrained supply, and overall uncertainty. In the G20 economies, consumers tend to complain most about the price of unleaded gas, which is affecting their ability to get around town and go on holiday. We look at how far north the G20’s gas prices have been driven.

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Private Bank

Citi Private BankJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

Big bad bear market

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos SantamariaIf you're an American worker with a 401(k), you're probably worried about being in the claws of a certain furry animal everyone seems to be talking about these days.

We're referring to a bear market, a Wall Street term for when the value of stock indices like the Dow Jones Industrial or the S&P 500 fall under 20% or more from a recent peak for a sustained period of time. Since bears hibernate, it’s investor-speak for a market in retreat.

On June 13, the S&P 500 officially entered bear market territory — with big implications for both investors and people who are indirect participants in the stock market through their 401(k), America's most popular company-sponsored retirement account. Simply put, since your 401(k) is likely invested in stocks, the longer the current slump lasts, the less money you'll have for retirement.

But that's only true if the bear market is still ongoing when you retire.

In other words, if you can afford to wait it out, odds are that the bear will eventually be followed by a bull (market) — aka a cycle of expansion — once the current economic turmoil subsides. Still, you might have a problem if you're a baby boomer with only a few years left to reach retirement age, in which case you'll have to crunch the numbers to decide whether it's best to cash out now — with less money, and pay taxes on what you withdraw — or pin your hopes on a swift recovery.

The thing is, no one knows how long bear markets last. The average historical duration is about a year, but in the early 1970s the bear stayed in its cave for almost two years, the S&P 500 lost half its value, and the US economy took a whopping 69 months to completely recover.

During the 2007-2008 Great Recession, the S&P 500 decline was even sharper (57%) and the market only recovered after 49 months.

Will the bear be followed by an even scarier recession? Maybe, but it's not guaranteed.

One key difference between the current US bear market and previous ones that preceded recessions is that unemployment is still very low at 3.6%. When Americans start losing their jobs at a higher rate, though, that's likely a sign that a recession is on the way.

What’s more, with the Fed getting tough on interest rates to tame sky-high inflation, it’s certainly possible that the US economy won’t hit the Goldilocks “soft landing” of bringing inflation down to about 2% while avoiding a recession (two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth).

Regardless, “making any prediction is unusually fraught” now due to an unprecedented set of shocks, including COVID and the war in Ukraine, says Robert Kahn, Eurasia Group's director of Global Macro-Geoeconomics.

Still, he adds, a recession seems more likely than not. It'll be painful, but not necessarily a catastrophe.

“Recessions can be moderate in tone,” Kahn explains. And whether or not we get one, “we’re going to have tremendous uncertainty heading into this slowdown period about how that plays out.”

What We’re Watching: US and China's rocky marriage and India’s unlikely success

China-US: Bad politics, good economics

President Joe Biden is a very different president than his predecessor, Donald Trump. But on some foreign policy issues – notably managing relations with China – the two are kindred spirits. US-China relations crashed under Trump, and Biden has kept the relationship on a mostly combative footing, leaving Trump-era tariffs on some Chinese goods in place. Still, while the White House talks tough about isolating China geopolitically, speculation of a US-China “decoupling” is misplaced. Beijing and Washington need each other because their economies are closely intertwined. The US is China’s biggest trading partner, with Americans importing a whopping $541.5 billion worth of Chinese imports in 2021. Even in 2020 – a slower trading year amid the pandemic – China and the US traded $559.2 billion worth of goods. What’s more, two-way foreign direct investment, which is more resistant to economic shocks, has ballooned in recent years (Chinese FDI in the US increased 61% between 2015 and 2020). The resilience of the bilateral economic relationship is also reflected in the fact that China is the third-largest export market for American goods (behind Mexico and Canada). Support for a tough-on-China stance gets rare bipartisan support in Washington these days, so political ties between Beijing and Washington will likely remain rocky. Still, with their economic fortunes so closely linked, China and the US are in this marriage for the long haul.

How is India doing so well?

On the surface, India seems to be having a moment. With record-breaking monthly exports and a post-pandemic bounce-back of 8.7% GDP growth pushing the size of its economy to $3.3 trillion, Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems well on his way to meeting his goal of making the country a $5 trillion economy before long. Meanwhile, both Russia and the West are courting Delhi as a key ally these days. But beneath the surface, not all is well. Despite Modi’s ambitious economic reforms, inequality remains stubbornly high, and the war in Ukraine has worsened inflation. Unemployment, meanwhile, is at 7.8%. In a country with 360 million people under age 15, that’s a big long-term problem. Meanwhile, Modi’s move to ban wheat exports has angered its Western partners, while the anti-Muslim bent of Modi’s ruling BJP party has antagonized Delhi’s Gulf partners. And of course relations with China, the other billion-strong Asian heavyweight, are strained. Modi looks secure at home, with no real opposition and a compliant media, but things aren’t getting easier for the world’s most populous democracy.Podcast: Could today’s crisis lead to future growth?

If you’re peeking out from under the duvet, wondering how to make it to 2023, be sure to listen up. In our latest “Living Beyond Borders” podcast from Citi Private Bank and GZERO Media, we examine the global risks setting the world on edge at the halfway point of 2022.

New COVID strains, supply chain issues, Russia’s war in Ukraine, climate change, soaring inflation, geopolitical decouplings — these are just a handful of the bubbling crises roiling the markets and the international order.

To delve into what’s happening in the markets and the future of financial growth and globalization, Eurasia Group’s Managing Director for Climate and Sustainability Shari Friedman speaks with David Bailin, chief investment officer and global head of investments at Citi Global Wealth, and Ian Bremmer, president of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media. Listen to their discussion here.Hard Numbers: Global malnutrition alert, Europeans’ bleak view of economy, South Korea’s export crunch, Xi’s confidence

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle Debinski8 million: Global food prices have risen amid the war in Ukraine, but it is particularly bad for emerging-market economies. UNICEF now says that up to 8 million children under the age of 5 could die from severe malnutrition in the coming months. The organization listed nearly two dozen “high risk” countries and urged developed states to step up and help.

-23.6: European confidence in the economy is going from bad to worse. The EU’s consumer confidence indicator for the eurozone plunged to -23.6 this month, the lowest it’s been since the peak of the pandemic in April 2020. Fears are mounting that the continent will soon fall into a recession as Russia tightens its grip on gas exports.

13: South Korean exports in the first 10 days of this month dropped 13% from the same period in 2021, a dramatic change from earlier this year when the country experienced an export boom amid the global post-pandemic recovery. The shift highlights the ongoing challenge for export-reliant economies amid the global inflation storm.

5.5: China’s economy has been pummeled by Beijing’s strict zero-COVID policy and a weakening housing market. But President Xi Jinping says his country is still on track to meet its 5.5% GDP growth goal this year. Economists, however, are skeptical and suggest it will be closer to 4%.

This edition of Signal was written by Beatrice Catena, Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Willis Sparks, and Carlos Santamaria. Edited by Tracy Moran. Graphic by Ari Winkleman, art by Paige Fusco.

Today, in a special edition of Signal, we look at how water scarcity is driving both conflict and progress. In the end, is the glass half empty or half full?

This edition is part of the “Living Beyond Borders” series presented by GZERO and Citi Private Bank.

Thank you for reading. Please tell your friends to subscribe here.

- The Signal team

An increasingly thirsty planet

A boy drinks from a water pump in a village outside Sanaa, Yemen.

REUTERS/Khaled Abdullah

The amount of water on Earth has been more or less the same for the past 4.5 billion years. But today, a growing number of the world’s people don’t have access to enough of it. In fact, nearly half of the world's population lives in places that face water scarcity for at least one month every year. And more than 1.2 billion people lack regular access to clean water altogether.

For many of them, the situation is getting worse by the day, as climate change causes more frequent droughts or conflicts prevent people from getting to freshwater sources. The lack of access to clean water for drinking, cooking, and crops can cause illness, starvation, and death.

Small wonder, then, that water scarcity is one factor behind some of the world’s most intractable conflicts: Israel-Palestine, India-Pakistan, and now Russia-Ukraine.

The desperate search for water also has millions on the move. The UN warns that water scarcity could force some 700 million people from their homes in the coming years, in mass migrations that will test governments, humanitarian organizations, and societies alike.

But it’s not all parched earth, thirst, and conflict. Water scarcity can also give rise to spectacular practical and technological innovations, as the examples of water management in the arid landscapes of Israel, Nevada, and South Africa show.

In this special edition of Signal, we’ll look at how the world is coping with water scarcity and what’s at stake for an increasingly thirsty planet.

What We’re Watching: Water wars vs. cooperation

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiWater wars?

Hundreds of millions of both Indians and Pakistanis depend on water from the Indus River for drinking, farming, and hydropower. The Indus Waters Treaty, signed by India’s prime minister and Pakistan’s president in 1960, guarantees how water from the river and its tributaries will be shared. This was put at risk in February 2019, when a suicide car bomb killed more than 40 Indian soldiers in the Indian-controlled sector of Kashmir. India’s transport minister responded with plans to “stop our share of water which used to flow to Pakistan.” The Pakistani government then warned it would treat any stoppage of water as an “act of war.” A treaty loses its values if one side decides not to honor it. Though tensions cooled in this case, the risk of a water war remains, because it’s simply too dangerous for these nuclear-armed and bitter rivals to fight a war with conventional weapons, and water will only become a more precious resource in coming years. Global warming could shrink the Himalayan glaciers that feed the river by more than a third in coming decades and make rainfall patterns more erratic, even as Indian and Pakistan water demand increases with population growth.

India and Pakistan are not the only rivals to successfully share water despite bitter differences on other questions. The five former Soviet Republics in Central Asia have not fought over access to the Aral Sea. Jordan and Israel haven’t waged war over the waters of the Jordan River. Threats over access to the Nile have not yet provoked war among Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt. A dispute over the Mekong River between China and its Southeast Asian neighbors has generated tensions but not widespread violence. Turkey and Armenia, neighbors with no diplomatic relations who have argued for decades over charges of genocide, have continued to share water from the Arpacay River, which forms the border between them. The two countries continued to honor the Soviet-era treaty that set water-use terms even while the two have fought on opposing sides of a war in 2020.

But successfully managed disputes of the past don’t guarantee a peaceful future, so these and other potential water-based confrontations are worth watching.

Can water cooperation bring peace to the Middle East?

Water scarcity is one of the biggest crises emanating from climate change. If current trends continue, the UN warns that 5 billion people — more than two-thirds of the global population — could be living in areas grappling with extreme water scarcity by 2050. Long dealing with irregular rainfall, increasingly arid conditions, and a growing population, Israel has emerged as a global leader in clean water solutions. Israel, a tech hub, recognized early the importance of treating wastewater to meet growing domestic needs and to leverage it as a tool for international cooperation. In 2000, Israel, which straddles the Sea of Galilee and the extremely salty (and undrinkable) Dead Sea, revamped its water management system by building a slew of desalination plants. It has also revolutionized water recycling, treating wastewater effluent to make the liquid ready for human consumption and irrigation. The country currently recycles about 86% of water, using much of it for agricultural purposes in the arid Negev Desert.

This innovation has also presented opportunities for “drought diplomacy.” Last year, Israel and Jordan, who have long enjoyed a frosty peace, outlined a water-for-energy deal that will see Amman exchange solar energy capacity for much-needed desalinated water. Meanwhile, Israel has also partnered with Arab states, Egypt, and Bahrain on water-management approaches and equipment to mitigate shortages at home.