Today, in a special edition of Signal, we look at how water scarcity is driving both conflict and progress. In the end, is the glass half empty or half full?

This edition is part of the “Living Beyond Borders” series presented by GZERO and Citi Private Bank.

Thank you for reading. Please tell your friends to subscribe here.

- The Signal team

An increasingly thirsty planet

A boy drinks from a water pump in a village outside Sanaa, Yemen.

REUTERS/Khaled Abdullah

The amount of water on Earth has been more or less the same for the past 4.5 billion years. But today, a growing number of the world’s people don’t have access to enough of it. In fact, nearly half of the world's population lives in places that face water scarcity for at least one month every year. And more than 1.2 billion people lack regular access to clean water altogether.

For many of them, the situation is getting worse by the day, as climate change causes more frequent droughts or conflicts prevent people from getting to freshwater sources. The lack of access to clean water for drinking, cooking, and crops can cause illness, starvation, and death.

Small wonder, then, that water scarcity is one factor behind some of the world’s most intractable conflicts: Israel-Palestine, India-Pakistan, and now Russia-Ukraine.

The desperate search for water also has millions on the move. The UN warns that water scarcity could force some 700 million people from their homes in the coming years, in mass migrations that will test governments, humanitarian organizations, and societies alike.

But it’s not all parched earth, thirst, and conflict. Water scarcity can also give rise to spectacular practical and technological innovations, as the examples of water management in the arid landscapes of Israel, Nevada, and South Africa show.

In this special edition of Signal, we’ll look at how the world is coping with water scarcity and what’s at stake for an increasingly thirsty planet.

What We’re Watching: Water wars vs. cooperation

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiWater wars?

Hundreds of millions of both Indians and Pakistanis depend on water from the Indus River for drinking, farming, and hydropower. The Indus Waters Treaty, signed by India’s prime minister and Pakistan’s president in 1960, guarantees how water from the river and its tributaries will be shared. This was put at risk in February 2019, when a suicide car bomb killed more than 40 Indian soldiers in the Indian-controlled sector of Kashmir. India’s transport minister responded with plans to “stop our share of water which used to flow to Pakistan.” The Pakistani government then warned it would treat any stoppage of water as an “act of war.” A treaty loses its values if one side decides not to honor it. Though tensions cooled in this case, the risk of a water war remains, because it’s simply too dangerous for these nuclear-armed and bitter rivals to fight a war with conventional weapons, and water will only become a more precious resource in coming years. Global warming could shrink the Himalayan glaciers that feed the river by more than a third in coming decades and make rainfall patterns more erratic, even as Indian and Pakistan water demand increases with population growth.

India and Pakistan are not the only rivals to successfully share water despite bitter differences on other questions. The five former Soviet Republics in Central Asia have not fought over access to the Aral Sea. Jordan and Israel haven’t waged war over the waters of the Jordan River. Threats over access to the Nile have not yet provoked war among Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt. A dispute over the Mekong River between China and its Southeast Asian neighbors has generated tensions but not widespread violence. Turkey and Armenia, neighbors with no diplomatic relations who have argued for decades over charges of genocide, have continued to share water from the Arpacay River, which forms the border between them. The two countries continued to honor the Soviet-era treaty that set water-use terms even while the two have fought on opposing sides of a war in 2020.

But successfully managed disputes of the past don’t guarantee a peaceful future, so these and other potential water-based confrontations are worth watching.

Can water cooperation bring peace to the Middle East?

Water scarcity is one of the biggest crises emanating from climate change. If current trends continue, the UN warns that 5 billion people — more than two-thirds of the global population — could be living in areas grappling with extreme water scarcity by 2050. Long dealing with irregular rainfall, increasingly arid conditions, and a growing population, Israel has emerged as a global leader in clean water solutions. Israel, a tech hub, recognized early the importance of treating wastewater to meet growing domestic needs and to leverage it as a tool for international cooperation. In 2000, Israel, which straddles the Sea of Galilee and the extremely salty (and undrinkable) Dead Sea, revamped its water management system by building a slew of desalination plants. It has also revolutionized water recycling, treating wastewater effluent to make the liquid ready for human consumption and irrigation. The country currently recycles about 86% of water, using much of it for agricultural purposes in the arid Negev Desert.

This innovation has also presented opportunities for “drought diplomacy.” Last year, Israel and Jordan, who have long enjoyed a frosty peace, outlined a water-for-energy deal that will see Amman exchange solar energy capacity for much-needed desalinated water. Meanwhile, Israel has also partnered with Arab states, Egypt, and Bahrain on water-management approaches and equipment to mitigate shortages at home.

Innovative solutions to water scarcity problems can be found globally. The US state of Nevada recently inked a deal with California’s government, whereby Nevada will dole out cash to help the Golden State develop new water treatment facilities in exchange for increased access to Lake Mead. Similarly, drought-stricken South Africa, once facing Day Zero – whereby taps were slated to be turned off in major cities like Cape Town because of water shortages – has successfully found a slate of tech-based solutions, particularly for the robust agriculture sector.

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Join us each week on Thursday at 11:30 am EDT for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

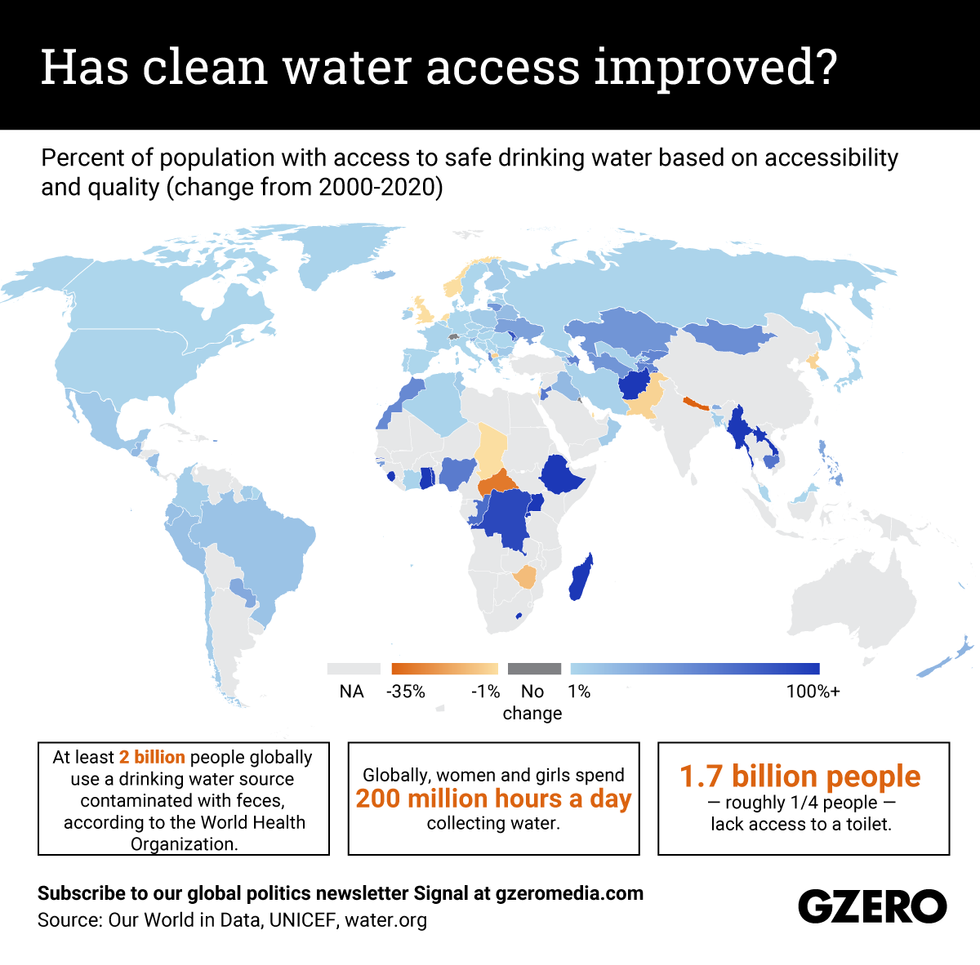

Gabrielle DebinskiIn many low- and middle-income countries, the availability of safe, drinkable water remains scarce. Though access has improved significantly in many places over the past two decades — by 152% in Afghanistan, for instance — the very low baseline means that still only 28% of that population has access to high-quality drinking water. Meanwhile, countries like the Central African Republic, Zambia, Nepal, and Pakistan saw their access reduced over the past two decades. Here’s a snapshot of the relative change in access to safe drinking water around the world from 2000 to 2020.

Podcast: Saving the world’s water supply

In our latest “Living Beyond Borders” podcast from Citi Private Bank and GZERO Media, we examine the global risks related to the depletion of a vital ingredient needed for everything in life: water.

Severe weather events and climate change are causing an urgent water crisis. By changing our natural world, through both big and small disasters, water scarcity is disastrously on the rise worldwide.

To delve into this immediate threat, Eurasia Group’s Director of Energy, Climate & Resources Mikaela McQuade talks to Franck Gbaguidi, senior analyst of energy, climate & resources at Eurasia Group, and Harlin Singh, global head of sustainable investing at Citi Global Wealth.

Listen to their discussion here.Hard Numbers: India’s record drought, privatized waterways, dripping wet smartphones, big oil meets little water

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos Santamaria669: Already sweltering amid a heatwave, the capital of India now faces water shortages with the level at Delhi's biggest reservoir dropping to 669 feet, a record low. The city’s government, run by the anti-corruption AAP party, accuses the BJP-ruled Haryana state of deliberately withholding water from the Yamuna River, which it denies.

454 billion: Private corporations control 454 billion cubic meters of water around the world, about 5% of the global supply. This water-grabbing is a major problem in Africa, where China, India, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE are investing big in water-intensive agriculture projects.

3,190: That smartphone in your hand is soaking wet – maybe (hopefully!) not literally, but it took 3,190 gallons of water to manufacture it. The production of chips and semiconductors – which are what make smartphones smart – is one of the world’s most water-intensive industries.

15.5 billion: Global fossil fuel, electric, and mining companies stand to lose up to $15.5 billion in the coming years due to water scarcity, according to a new report. Projects at high risk include the Keystone oil pipeline in Canada, the Pascua-Lama gold mine on the Chile-Argentina border, the Carmichael coal mine in Australia, and the Oyster Creek nuclear facility in the US.This edition of Signal was written by Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. Edited by Tracy Moran. Graphic by Ari Winkleman. Art by Luisa Vieira.