Tensions between Taiwan and China rose to new highs this summer after US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to the island prompted a week-long series of Chinese military maneuvers that were even more threatening than usual. China has pledged to retake what it sees as a breakaway territory — through invasion if necessary — and viewed the trip by a top US official as an affront to its sovereignty.

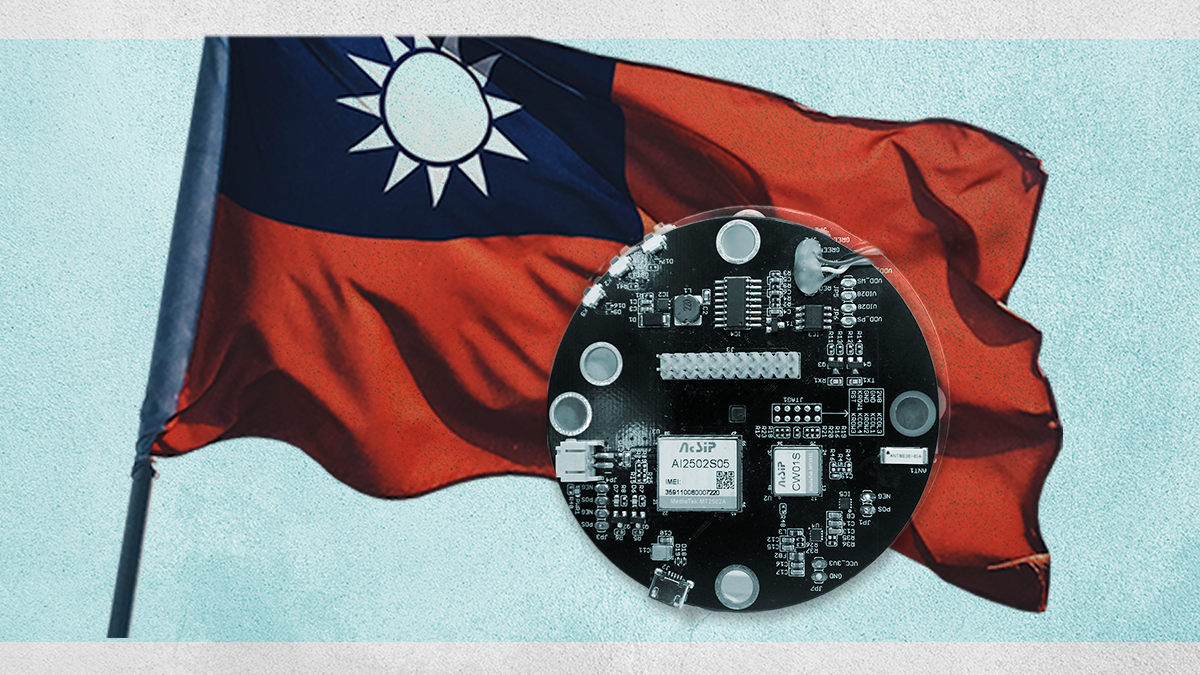

As China asserts its claims to Taiwan more aggressively, the island’s population has grown increasingly averse to reunification. Yet there are powerful reasons for China not to invade Taiwan — not least the fear that America, the island’s longtime ally, would come to its defense. US ties to Taiwan have grown even closer in recent years as it has come to dominate the global production of semiconductors, tiny silicon connectors that serve as the brains of modern electronics.

We asked Xiaomeng Lu, a director in Eurasia Group’s geo-technology practice, to explain how chips fit into Chinese and US calculations toward Taiwan.

How important is Taiwan for the world’s electronics industry?

A single company, TSMC, produces more than 90% of the world’s smallest and most advanced semiconductors, which are used to power high-end servers and sophisticated AI applications. Taiwan is also home to MediaTek, a leading manufacturer of smartphone chipsets; ASE Group, which provides semiconductor assembly and testing services; and GlobalWafers, which makes silicon wafers. Other important Taiwan firms include PC makers ASUS and Acer, as well as contract manufacturers Foxconn, Pegatron, and Wistron. The island’s manufacturing capacity plays a critical role in the global electronics supply chain.

What would be the impact of a Chinese invasion?

Modern semiconductor manufacturing is a complex global ecosystem in which different companies around the world have different specializations. A Chinese invasion would cut Taiwan off from that ecosystem, severing the real-time connections it relies on for things like product designs, materials, chemicals, and equipment. Even in the best-case scenario for China of a rapid, successful invasion in which it gained control of the island without much fighting, international sanctions would probably prevent China from obtaining many key inputs from overseas required to produce chips.

Yet as Russia’s attempt to take over Ukraine has shown, such a move is fraught with risk and uncertainty. An invasion of Taiwan by China would be even more complex, given the body of water separating them. Many semiconductor production facilities are located in areas where China is likely to land troops, so chipmaking offices and factories could unintentionally suffer collateral damage. A prominent Chinese economist affiliated with the government recently said that occupying TSMC factories would be a top priority for China in the event of an invasion. But Taiwan, potentially with US assistance, might choose to destroy them itself rather than let them fall into the hands of China.

How do these risks affect China’s calculations?

Recent events in Hong Kong show that China is willing to inflict damage on a high-performing economy, if necessary, to achieve longstanding political goals. The wrinkle in the case of Taiwan is that its high-tech products – especially its semiconductors – are key to China’s ambitions to establish itself as a global leader in emerging technology areas. Cutting-edge chips support, for example, space and biology research; exposure to advanced technology also offers Chinese engineers the opportunity to acquire new skills.

As a result, China has aimed to maintain commercial ties with TSMC and avoid any measures that would harm it or the broader sector even as its relations with Taiwan and the US have deteriorated. Following Pelosi’s visit, China slapped several sanctions on Taiwan, including a prohibition on the export of Chinese sand for use in the island’s semiconductor industry. This was a purely symbolic measure, however, as Taiwan chip manufacturers do not use Chinese natural sand in silicon wafer production but high-purity quartz sand, primarily obtained from the US.

How worried is the US?

US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo recently said the loss of access to chips from Taiwan would cause a “deep and immediate recession” for the world economy. The current global chip shortage, caused by pandemic-related disruptions, provides a small taste of what a semiconductor supply chain crisis may look like.

Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan included meetings with top semiconductor executives including TSMC Chairman Mark Liu and founder Morris Chang. Pelosi reportedly discussed with them the recently passed CHIPS+ Act, which offers $52 billion in support for semiconductor production. The US has been encouraging TSMC to expand its operations in the US to strengthen ties with the company.

Observers have referred to Taiwan’s unique status in the semiconductor industry as a “silicon shield” that both discourages Chinese aggression and encourages US backing for the island.

How has the Taiwan semiconductor industry navigated escalating geopolitical tensions?

Though TSMC has tried to maintain good relations with China, it has moved closer to the US to maintain access to its technology and political alignment with Taipei. The company has committed to building a $12 billion advanced semiconductor plant in Arizona and has expressed interest in receiving CHIPS funding to cover some costs.

However, TSMC has resisted pressure to shift its most cutting-edge production technology to the US, citing concerns such as commercial feasibility, talent shortage, and cultural issues. It is also likely responding to Taipei’s concerns that doing so could erode US resolve to come to Taiwan’s defense in the event of an attack. Nobody on the island wants to weaken the “silicon shield” protecting it.