In this special edition of Signal, we'll take a look at the growth, future, and political challenges of the places where most of us live… cities. This edition is part of "Living Beyond Borders," a joint project between GZERO Media and Citi Private Bank that explores how global political trends affect people's lives.

- The Signalistas

Cities on the frontlines

Alex Kliment

Alex KlimentWe live on an (increasingly) urban planet. Today, for the first time in human history, more than half of the world's population (55 percent) lives in cities. By 2050, that figure will rise to more than two-thirds, with close to 7 billion people living in urban areas. Cities have always been centers of opportunity, innovation, and human progress. But they are also often on the front lines of the major political and social challenges of the day. Here are four areas in which that's true right now.

Climate change. Cities are hugely vulnerable to climate change and will have to take the lead in efforts to contain and adapt to it. More than 90 percent of the world's cities lie in coastal areas exposed to rising sea levels. At the same time, large cities' traffic, transport infrastructure, and buildings are responsible for 75 percent of global carbon emissions.

The major global climate change agreements — like the Paris Accord — exist at the national level, but implementation falls largely on cities. Many large cities are already taking the lead on their own — in some cases (as in the US currently) working at cross purposes with national leaders who are climate skeptics.

Technology. Urban planners are excited about "smart cities" where digital technologies (including sensors and cameras deployed across the city) can make the city more efficient, less polluted, and more responsive to citizens' needs. But there are two big political issues here.

First, who's watching all of this? All of those data flows have to be monitored and safeguarded by someone. As cities get "smarter" they'll wrestle with politically fraught tradeoffs between urban efficiency and personal privacy.

Second, who's making all of this? Smart cities require next generation 5G networks. Right now, the most cost-effective manufacturers of 5G equipment are Chinese companies. But the US government has banned them at home over national security fears and is pressuring other countries to do the same. As the world slouches towards a bigger US-China tech divide, cities that want the technologies of the future will be caught in the middle.

Pandemic. All of the things that make cities vibrant centers of progress and innovation – density, diversity, strong connections with the rest of the world – also make them sitting ducks for outbreaks of contagious disease. That's been particularly true of the coronavirus pandemic. COVID-19 first spread in a city (Wuhan, China — population 10 million) and since then, the overwhelming majority of the disease's victims have been in cities. In the US, for example, a study in June found that more than 94 percent of all cases (and deaths) have been in urban areas.

When we talk about the devastating impacts of the pandemic, and particularly its disproportionate public health and economic effects on minorities, the poor, and women, we are talking primarily about urban crises.

Polarization. No matter who wins next week's US presidential election, the electoral map is likely to be a sea of red (many less densely populated precincts that voted Republican) with large islands of blue (Democrat-leaning cities). But that political divergence between more liberal big cities and more conservative towns and rural areas isn't just an American phenomenon.

In 2016, for example, Londoners overwhelmingly voted against Brexit. Poland's recent presidential election was similar, a right-wing conservative beat a liberal big city mayor by drawing votes from the countryside. In Turkey, strongman president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is least popular in the big cities, particularly his hometown of Istanbul, which his party lost control of last year.

The political divergence between town and country, and between cities and national governments, will become increasingly acute as cities grow and gain more economic power.

The Graphic Truth

Carlos Santamaria

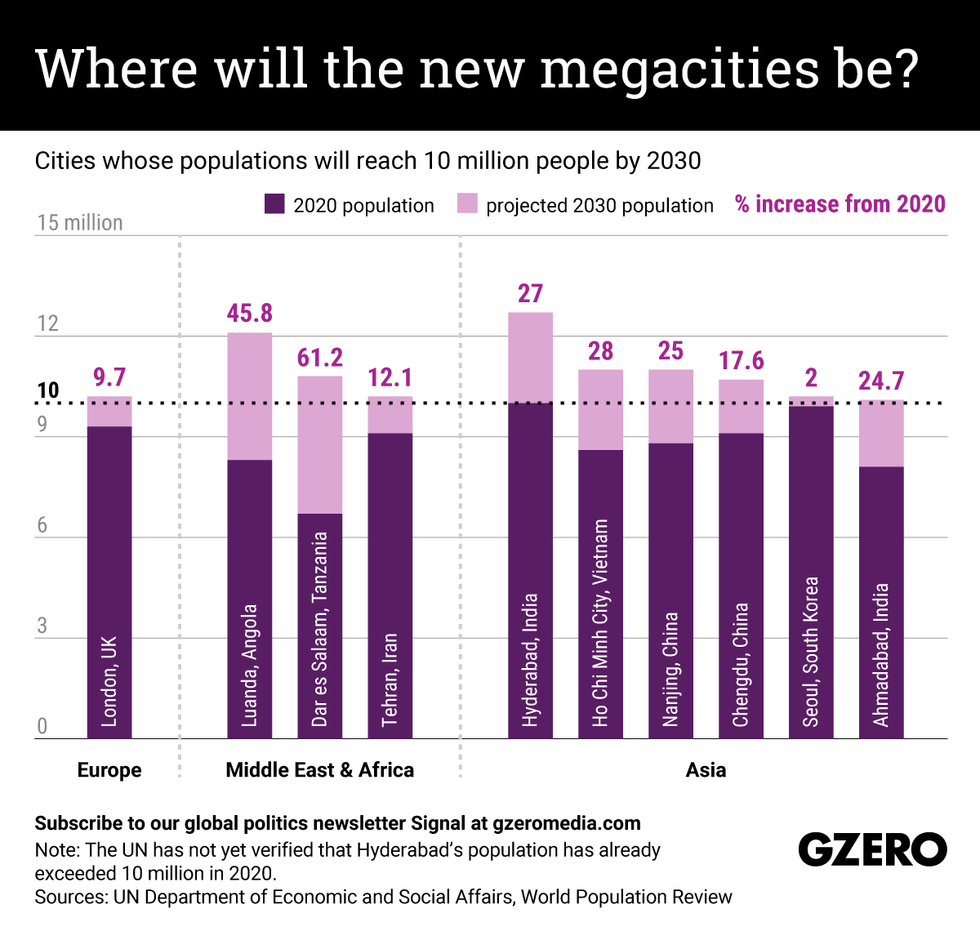

Carlos SantamariaBy 2030, ten urban areas are projected to attain "megacity" status, a population of more than 10 million people. Six will be in Asia, where more than half of the population will be living in cities at the end of the decade. But the fastest growing megacities will be in Africa — including new megacities in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) and Luanda (Angola). Can urban planners and governments in Africa keep pace with this rapid urban growth? We look at the world's upcoming megacities, comparing their current and future estimated populations, to get a sense of how crowded each megalopolis will be in 2030.

Join us for four virtual events starting on November 10

Urbanization may radically change not only the landscape but also investors' portfolios. Creating the livable urban centers of tomorrow calls for a revolution in the way we provide homes, transport, health, education and much more.

Our expert guests will explore the future of cities and its implications for your wealth.

PODCAST: Big cities after COVID-19 — boom or bust?

The coronavirus crisis has hit cities particularly hard. How will that affect what our cities look like in the future, and what role can local governments play in addressing the socioeconomic inequalities that the pandemic both illuminated and exacerbated? In this special podcast, Signal's Alex Kliment discusses this and more with Ida Liu, Citi Private Bank's Head of North America, in a conversation moderated by Eurasia Group's Caitlin Dean. Listen here.

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

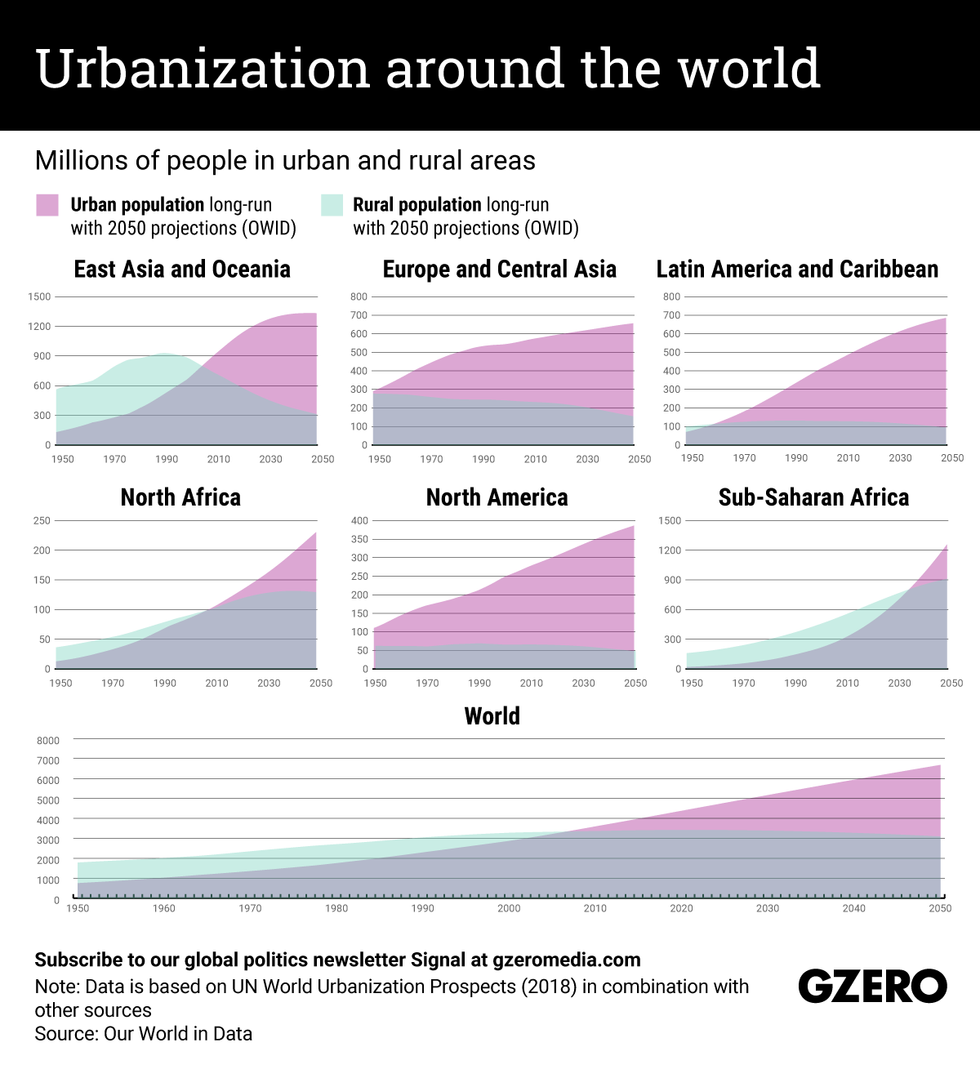

Gabrielle DebinskiOver the past seven decades, dozens of countries have experienced rapid urbanization as people flock from rural areas to cities in search of more diverse economic opportunities. During that time, the global urban population has increased six-fold. Here is a look at how that trend has played out in major regions of the world. While North America and Latin America have been predominantly urban for decades, it is only more recently that East Asia has made this transition, while sub-Saharan Africa is just on the cusp of being majority urban. Here is a look at how urbanization played out globally since 1950, with forecasts out to 2050.

What We’re Watching: The perfect city, cities vs nations, the post-pandemic planning problem

Willis Sparks

Willis SparksThe construction of China's "perfect city" In April 2017, China's President Xi Jinping personally chose the site for the Xiongan New Area, about 60 miles south of Beijing. What's the Xiongan New Area? It's not only an attempt to relieve the crushing congestion of China's capital city, it's a bold bid to create a "city of the future." Of the 1,000 "smart city" projects around the world, half are in China, and Xiongan is the most ambitious in scale. Its architects say it will serve the needs of citizens with high-tech smart infrastructure and higher environmental standards than exist elsewhere in heavily polluted China. But it will also serve as a laboratory for cutting-edge surveillance of the city's residents. By following its progress and measuring its successes and failures, we'll learn much about how "smart cities" can create a higher quality of life for us all — but also how governments can use new tools to compromise personal privacy in the name of social order. The Xiongan project, with full political and financial backing of the Chinese government, is due for completion in 2035.

Cities going at it alone: Last December, the mayors of four Central European capitals got together and promised something big to the European Union: "miracles." At a time when the EU was threatening to withhold funding for increasingly illiberal national governments of Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia, the progressive and liberal big city mayors in these countries asked Brussels to just give them the money directly so they could work "miracles" in areas like climate policy. This trend of big cities increasingly looking to operate independently of their national governments — and alongside each other — on transnational issues like climate change, cybersecurity, or immigration has become more pronounced in recent years, particularly in countries where the political divide between progressive cities and more conservative national governments is increasing. The coronavirus pandemic has shed a new light on that trend. On the one hand, as the disease tore through cities around the world, big cities in some of the hardest hit countries — like the US and Brazil — found themselves fighting the disease without much help from pandemic-skeptic federal governments. This forced cities and states to act more independently in areas like sourcing PPE for their healthcare workers, imposing quarantines, or deciding when to reopen schools. But here's the question: given that the economic impact of the pandemic has hit urban areas particularly hard, will that broadly make cities more dependent on national governments in the coming years as they look for much-needed stimulus and recovery funds?

How will COVID-19 affect future urban planning? While it's easy to assume that the pandemic will "destroy" highly congested urban centers, throughout history some modern cities actually benefited in the long term from the lessons learned from dealing with a public health crisis. For instance, London only embarked on the engineering marvel of its present-day sewer system after it was crushed by cholera — a water-borne disease — in the 1850s. Urban planners widely expect that future cities will be designed to be healthier for residents. But which cities will have the cash to reinvent themselves as "safer" areas to live and work? The coronavirus has wreaked economic havoc on urban centers worldwide in developing and developed countries alike, and cash-strapped local and national governments may prioritize getting people back to work and helping those who have lost jobs. We're watching to see which mayors will see the wisdom in spending on pandemic-proofing their cities, and which cities will get left behind because they made a false choice by thinking only about their short-term problems.

Hard Numbers: London’s languages, US cities' economic boom, Asia’s concrete jungles, Addis Ababa's bike love

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle Debinski300: London — a city where a large chunk of the population is foreign born — is home to the world's most internationally diverse student body. More than 300 languages are spoken by London's school students, many of whose families immigrated from South Asia, Africa and Europe.

70: In the decade following the 2008 global financial crisis (which left more than 11 million Americans unemployed within months), America's largest cities — including San Francisco, Boston, and New York — accounted for over 70 percent of the country's job growth. By contrast, unemployment is still at pre-2008 levels in many American rural areas and small towns.

39: Public green spaces like parks and nature reserves, which many city dwellers have flocked to in COVID-19 times, are a luxury in most of Asia's crowded urban centers. In the region's 22 major cities, average green space per capita is only 39 square meters (420 square feet), about half of the figure in Africa and more six times smaller than the per capita average in Latin America.

800: Many big city governments struggle with traffic congestion, but in developing economies the problem is often exacerbated by poor infrastructure. The answer isn't always to build more roads: Addis Ababa has an ambitious plan to build 800 kilometers (490 miles) of bike and pedestrian lanes by the end of the decade.

QUIZ TIME: What do you know about cities?

1. In the year 1650, what was the most populous city in the world?

a. London

b. Istanbul

c. Beijing

2. Pandemics have reshaped cities throughout history — which of these major urban landmarks was directly related to post-pandemic planning?

a. New York's Central Park

b. Rome's Colosseum

c. Cairo's Khan el-Khalili marketplace

3. In 1960, the federal capital of Brazil was moved to a new city, Brasilia, designed and built from scratch in a remote swath of desert by the visionary architects Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa. Where was Brazil's capital before that?

a. São Paulo

b. Rio de Janeiro

c. Belo Horizonte

QUIZ ANSWERS:

1 — B. In 1650, Istanbul was the largest city in the world, with an estimated population of 700,00 people. The second largest city then was Edo (Tokyo), with 500,000.

2 — A. The cholera epidemic of 1832 in New York spurred planners to create "lungs for the city" — Central Park was one of the major results of that initiative, along with a modern aqueduct and water system, which turned out to be a more effective way to eradicate cholera, which is water-borne.

3 — B. Until 1960, Brazil's capital was in the "marvelous city" of Rio de Janeiro.

Follow us on Twitter and Instagram. If a friend sent you this email, you can subscribe here.

This edition of Signal was written by Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. The arts were made by Annie Gugliotta and Gabriella Turrisi, and graphics by Ari Winkleman and Gabriella Turrisi.

Spiritual counsel from Walter Ruttmann, who knew how to make a city sing — silently. What's your favorite "city" film?