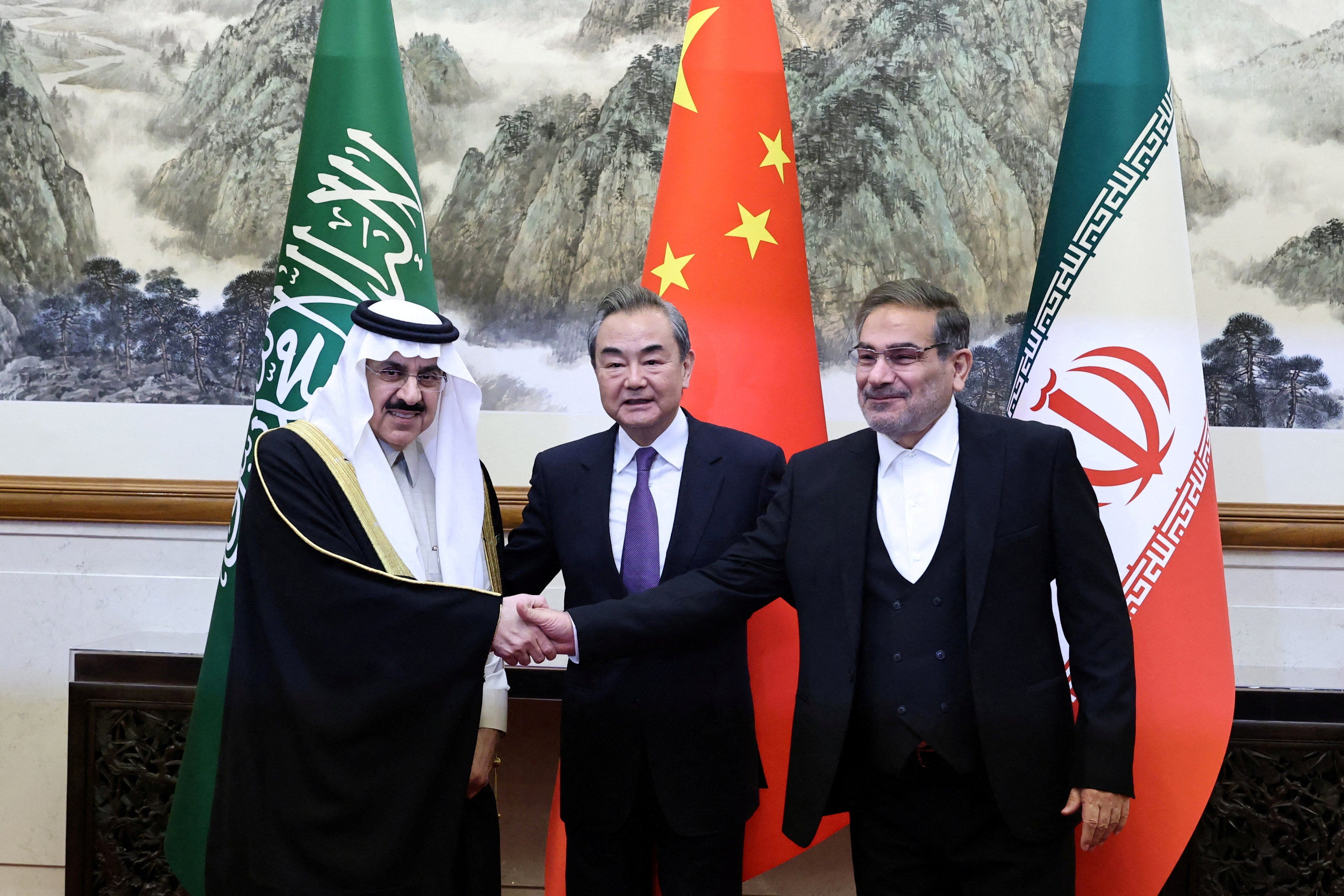

“Welcome to the post-America moment in the Middle East,” one commentator wrote after the surprising news broke last week that China had mediated a diplomatic breakthrough between two forever enemies: Iran and Saudi Arabia. Others hailed the exciting prospect of peace between two countries that have long been locked in regional proxy wars.

But are these hot takes jumping the gun? Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the country’s de facto decision maker known as MBS, once said Iran’s supreme leader “makes Hitler look good.” So why has he bought into this rapprochement – and why now?

First, what’s actually in the deal? Last Friday, Saudi Arabia and Iran announced that they had agreed to restore full diplomatic ties within two months after China stepped in to mediate a deal. While the announcement was light on details, Riyadh and Tehran have broadly committed to reopening diplomatic missions in each other's capitals, as well as to activate security arrangements, though it is unclear exactly how they would stamp out proxy wars in places like Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, where they have divergent interests.

While the two states have long been divided over competing visions of Islam and vied for regional dominance, diplomatic relations were severed entirely in 2016 after the execution of a Shiite cleric in Saudi Arabia prompted Iranian protesters to storm the Saudi mission in Tehran.

If diplomatic breakthroughs come and go, why is this one such a big deal? First, whether in the schoolyard or at the negotiating table in Geneva, it’s always a feat when two sides that seemingly hate each other say they’re willing to patch things up.

What’s more, when it comes to moderating Mideast rivalries and inserting oneself in the region’s affairs – whether wanted or unwanted – the US has almost always played the part. This time, however, China, which is in the increasingly rare position of having warm ties with both Riyadh and Tehran, stepped in at the eleventh hour to see negotiations, previously led by Iraq and Oman, over the finish line.

Who wants what? China isn’t necessarily interested in taking up the mantle of Mideast security guarantor, says Simon Henderson, an expert on Gulf and energy policy at The Washington Institute. “I think that China is focused on displacing the US rather than being embroiled in managing Gulf schisms,” he says.

Moreover, for Iran, the perks of such a détente are more or less clear. Having faced a recent popular uprising at home – which it initially blamed on the Saudis for orchestrating (not true!) – combined with a deepening currency crisis and having very few friends to turn to, a cold peace with the richest Gulf state could eventually give its economy some breathing room.

Less clear, however, is why the Saudis – who have long enjoyed a very complicated partnership with the US while sounding the alarm on Iran’s menacing nuclear ambitions – are willing to back the deal in good faith with few security guarantees.

Deteriorating Saudi-US ties: Desperate times call for desperate measures. Riyadh has long perceived Tehran – and its regional proxies in Yemen, Lebanon, and elsewhere – to be its biggest security threat. This view was fortified in 2019 when Iranian-backed groups in Yemen fired missiles on Saudi oil infrastructure, temporarily knocking out a whopping 5% of global oil supplies.

Riyadh was furious that its friend in the White House – former President Donald Trump – first said that the US was “locked and loaded” to respond to the attack, but then proceeded to do … nothing. The Kingdom’s view that it could not rely on the US to have its back was reinforced in 2020, when then-presidential candidate Joe Biden vowed to make Riyadh a “pariah.”

“Whether or not this latest move was intended as a middle finger to the Biden administration I don't know,” says Aaron David Miller, a senior fellow and Middle East policy expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “but I do think that MBS has a very low opinion of and regard for Biden.”

Indeed, as a result of deteriorating relations with Washington, the wily and pragmatic Saudi crown prince has sought to deepen ties with other dominant global players – like China and Russia – as well as pursue politically expedient rapprochements with rivals (first Qatar and now Iran) on its own terms without the US leading the way.

It is possible that Riyad’s game plan here is to pressure the Biden administration into committing to security guarantees for the Saudis and providing them with what they have long been asking for, Henderson says, including, “guaranteed access to US weapons systems, no role for Congress in approving [weapons sales], and nuclear technology without signing additional protocol.” Chances? “Each is ... a stretch,” he says.

Why now? Stability is key to economic expansion. For the Saudis, long focused on diversifying their economy away from hydrocarbons, a dying breed, de-escalating regional tensions (combined, of course, with addressing its serious reputation issues) is key to luring the investment needed to get new industries off the ground. What’s more, Riyadh has benefited from high oil prices over the past year and is likely keen to use this cash influx to boost the non-petroleum economy – like its nascent mining sector – in the near term.

Ambiguity is the point. The Iran-Saudi row is so bitter and protracted that it’s hard to believe Riyadh has much faith this new deal will yield significant changes in Iranian behavior.

After getting the cold shoulder from Biden, Riyadh’s message to Washington appears clear: We have other friends in high places. While that may be true, China is hardly in a position to provide the security guarantees that Washington does, including, ironically, protecting the passages that allow Saudi to export its oil to … China.

In this way, Miller says, from the Saudi perspective, the deal can be seen more as a “hedge” against Iran. “Getting the Chinese to broker what amounts right now to a stylized ceasefire – it's more a transactional arrangement than it is anything else” – might help the Saudis by “preempting or ameliorating a crisis,” he says.

Washington’s poker face. The Biden administration welcomed the recent announcement, saying that reconciliation is always a good thing. It also embraced the idea that this could finally lead to a resolution of the devastating Yemen civil war, something Iran and Saudi Arabia both seem open to.

Still, Miller’s take? Washington’s stance is overwhelmingly “passive aggressive,” he says. “When your presumptive partner is drawn into an agreement with your preeminent international rival and your preeminent regional rival, you can't be happy about that."

More For You

In this Quick Take, Ian Bremmer weighs in on the politicization of the Olympics after comments by Team USA freestyle skier Hunter Hess sparked backlash about patriotism and national representation.

Most Popular

100 million: The number of people expected to watch the Super Bowl halftime performance with Bad Bunny, the Puerto Rican superstar and newly minted Album of the Year winner at the Grammys.

Brazilian skiers, American ICE agents, Israeli bobsledders – this is just a smattering of the fascinating characters that will be present at this year’s Winter Olympics. Yet the focus will be a different country, one that isn’t formally competing: Russia.

What We’re Watching: Big week for elections, US and China make trade deals, Suicide bombing in Pakistan

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, president of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), appeals for a candidate during a street speech of the House of Representatives Election Campaign in Shintomi Town, Miyazaki Prefecture on February 6, 2026. The Lower House election will feature voting and counting on February 8th.

Japanese voters head to the polls on Sunday in a snap election for the national legislature’s lower house, called just three months into Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s tenure.