The UN General Assembly turns 80 this week, and the mood is grim. It’s not just the awful motorcade traffic in New York (do yourself a favor, walk or take the subway). Wars rage in Ukraine, Gaza, and Sudan. Autocrats flex their muscles with impunity. Democracies are fracturing at the seams. International cooperation is fraying as the G-Zero takes hold.

You'd think Climate Week – happening simultaneously in the Big Apple through September 28 – would add to the gloom given President Donald Trump’s skepticism of climate change (“the greatest con job ever perpetrated”) and outright hostility toward clean energy (a “scam”). But there's some genuinely good news for the planet buried in all this chaos: We may be at – or very near – peak oil demand.

This isn’t the old “peak oil” story that doomsayers have predicted for decades – the moment when the world runs out of accessible oil. Those theories have been proven wrong time and again – most recently when fracking and other extraction technologies turbocharged the industry’s productivity, unlocked new barrels, and turned the United States into the world’s top producer and exporter. What I’m talking about here is different. We're likely witnessing the moment when global appetite for oil finally starts to wane, driven not by scarcity but by changes in how the world consumes energy.

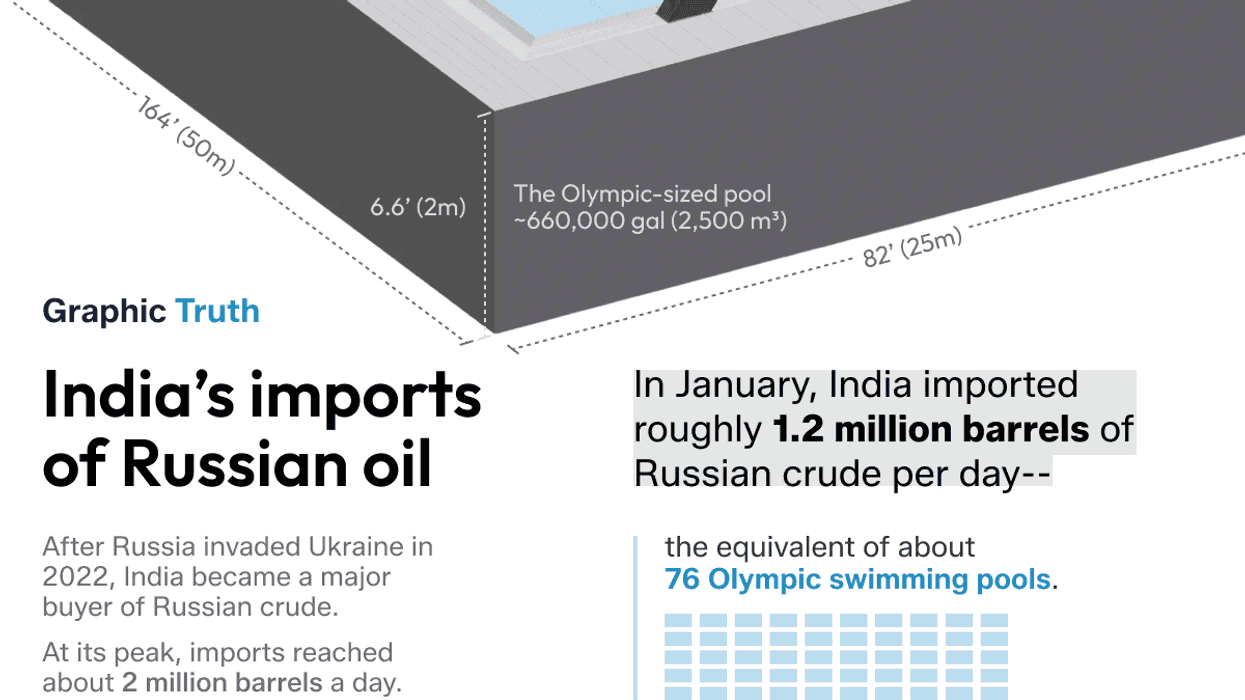

The most dramatic shift comes from China, whose appetite for fossil fuels kept global oil markets humming for thirty years. Between 2010 and 2020, Chinese oil imports doubled to 10 million barrels per day. That era looks to be over thanks to a demographic transition, a rapidly accelerating energy revolution, and slowing economic growth.

Start with demographics. China’s population peaked during Covid but has since shrunk by nearly 25 million people – roughly equivalent to Denmark, Sweden, and Norway combined – after growing by more than 155 million in the previous twenty years. Fewer people means less demand for gasoline and diesel – especially in a decelerating economy weaning itself off a housing and infrastructure construction binge.

Then there’s China’s energy revolution. In just five years, electric vehicles’ share of new car sales in China jumped from roughly 5% to over 50%. That alone took what used to be the world’s single largest growth market for gasoline off the table. But China’s technological transformation has gone far beyond cars. Beijing is also rapidly electrifying heating and heavy industry while deploying renewable power capacity (especially solar) at a historic scale. The country installed almost 270 gigawatts of new renewable energy in just the first half of 2025 – more than twice the new capacity installed by the entire rest of the world in the same period, six times what the US managed in all of 2024 at the heyday of Bidenomics, and more than India’s entire installed renewable capacity. The result: China’s oil demand has likely topped out and could enter structural decline as soon as this year, joining Europe and North America.

Not even a fast-growing India will be able to fill China’s shoes. Though still rising, Indian oil consumption growth has been uneven, slowed this year by infrastructure constraints. Unlike China’s, India’s economic expansion relies more on services than on oil-intensive sectors like construction and chemicals. The country is also now entering its own electrification phase. New Delhi wants EVs to reach a third of new auto sales by 2030, up from roughly 5% today. Even if that target slips, the direction of travel is unmistakable – especially as renewable technologies continue to get cheaper and better. India won’t fully replace China’s lost oil-demand growth.

Add it up and it’s increasingly plausible that global oil demand could shrink in 2025. Yes, consumption remains at record highs. But global demand growth has flatlined since the pandemic. Oil intensity across power, transport, and heating is plummeting everywhere. In the biggest consuming economies, oil use per capita has dropped by more than 15% over the past two decades. Europe’s green transition is uneven but persistent. America’s is slower than it could be but still ongoing, with renewables set to meet most incremental power demand because they’re cheaper to build and quicker to deploy at scale – the Trump administration’s “war” on them be damned.

Peak demand may not happen this year. Heck, it may not happen for another five or ten years. Prediction is hard, especially about the future. The debate on this question is as much political as it is analytical. That’s why the Trump administration has threatened to withdraw from the International Energy Agency over its “politicized” forecast of peak demand by 2030 – never mind that oil companies like Equinor and BP project a similar inflection point. But even the skeptics – especially the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and Exxon Mobil – now only quibble about the “when,” not the “if.”

So how are oil producers responding to the existential prospect of a shrinking market? Not by cutting supply and creating a deficit that lifts prices, as you’d expect, but by pumping more. In fact, after cutting for years, Saudi Arabia and its OPEC+ allies are on track to raise output by more than 1 million barrels per day year-on-year despite stagnant demand growth. They're determined to regain market share from their non-OPEC competitors – particularly the US – by keeping the taps open and squeezing out the highest-cost producers, even if it means lower prices for themselves. Non-OPEC supply, however, is stubborn. US production hit a record this summer and will likely plateau rather than crash as industry consolidation, cost discipline, and efficiency gains keep shale output resilient. Brazil and Guyana will continue adding low-cost offshore barrels. And Norway can keep pumping into Europe almost regardless of global pricing.

The combination of weaker demand and increased supply will result in a world awash in relatively – and increasingly – cheap oil. This doesn't mean prices will crash to zero. The world will use lots of oil for a long time, and prices need to stay high enough to induce the necessary supply. OPEC can pivot to cutting if it wants to (though the cartel’s coordination and market-management powers are likely to weaken as the energy transition advances and structural demand for oil wanes). Output, investment, and prices will ebb and flow with business cycles, shocks, and geopolitical developments. But the overall environment points to lower demand and softer prices.

For consumers, this is a gift. Cheaper oil will be a boon to households and oil-importing economies across Northeast Asia, Western Europe, India, and parts of Southeast Asia and South America. For oil producers, not so much. Countries whose entire budgets are predicated on $80-$100 oil are about to face a reckoning.

The geopolitical implications are stark. China's strategic bet on post-carbon energy dominance looks to be paying off. The country that was arguably the most fossil fuel-dependent on Earth in 2010 is now the world's first "electrostate.” Not only is it the largest consumer of clean energy by orders of magnitude, but it has cornered the market on both the finished products and the key supply chains that drive the transition globally – batteries, EVs, solar panels, critical minerals. By contrast, the Trump administration’s decision to double down on America’s petrostate status while waging war on renewables has near-term political utility, but it’s a losing play in a world that will be increasingly powered by electrons, with implications for economic competitiveness, AI dominance, and national security. Beijing’s recent weaponization of its rare earths dominance was just a glimpse of what the US has risked by ceding leadership and leverage to the Chinese in the electrotech space.

A near-term peak in global oil demand is good news for the climate fight. The world’s biggest emitter is now seeing its first drop in emissions driven by the growth of renewables. Critically, China is also exporting massive amounts of cheap renewable tech to developing countries, helping them leapfrog the dirty growth phase every industrialized country has had to go through in the past.

That’s not to say climate is a solved problem. Aviation, shipping, petrochemicals – these sectors are hard to abate and will keep running on fossil fuels for the foreseeable future. Persistently low prices can also disincentivize change at the margins. Plus, mass electrification requires upfront capital spending – lots of it. Solar and wind have become the cheapest form of energy in most sectors across much of the world, but you still need to build grids, storage, and charging at scale. Governments facing weak economic growth, high interest rates, and tight budgets will struggle to fund the infrastructure investments they need to turn cheap kilowatt-hours into lower bills. That keeps the politics of the transition messy, particularly in the US and parts of Europe, where there are tons of potentially stranded assets and powerful vested interests.

Not to mention that a world in which Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party save the world from climate change will look quite different from one in which the United States and its democratic allies do. It won’t matter to the planet. But it’ll make a difference for the future of democracy and the balance of power.