March 25, 2021

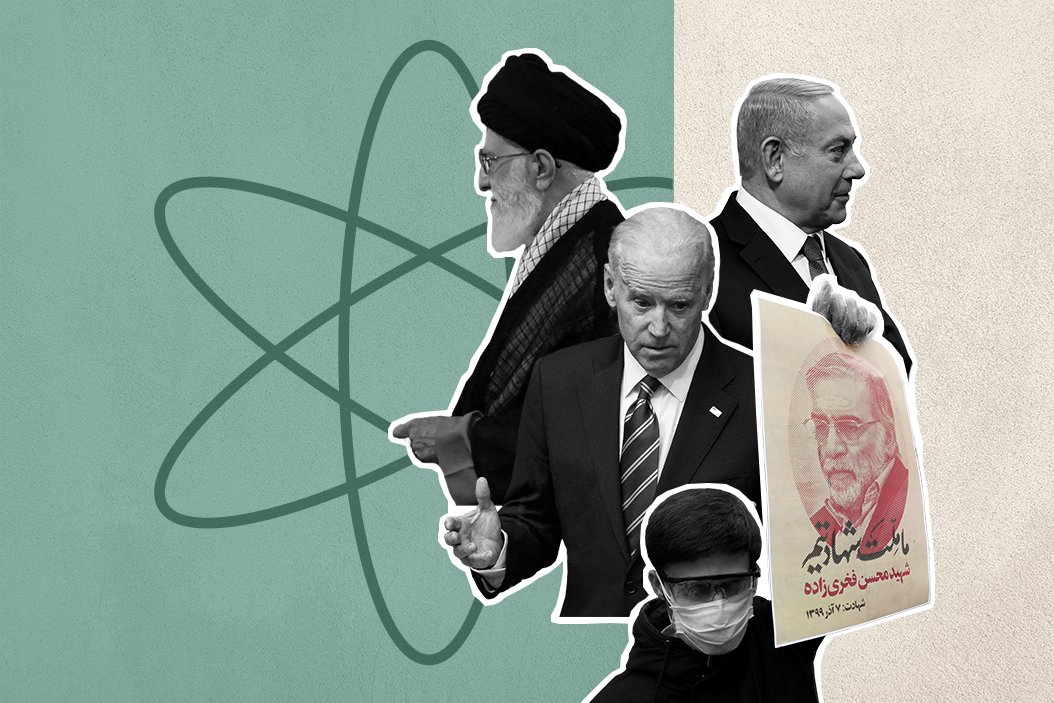

Joe Biden is the fifth American president in a row to pledge to stop Iran from developing a nuclear weapon. Even amid escalating tensions with Tehran, Biden is aiming to negotiate a revival of the 2015 nuclear agreement that Donald Trump's administration walked out of in 2018. What lies behind this abiding American concern about Iran's nuclear capacity? Eurasia Group senior analyst Henry Rome explains how we got here, and what comes next.

Why is the international community so preoccupied with whether Iran gets the bomb?

The concerns can be broken down into three categories. First, many believe that if Tehran got the bomb, it could use it. Those anxieties are most acute in Israel, given Iranian threats to destroy the Jewish state and its support for terrorist groups that have attacked Israelis and Israeli interests.

Second, there's a concern that even if Iran did not use the bomb, it would leverage the political power of having one to expand its influence in the Middle East and more effectively bully other states into accepting its demands.

Lastly, there's the issue of precedent. If Iran got the bomb it would severely undermine international efforts to stem the spread of nuclear weapons, and would harm Washington's credibility, given that it's insisted for years that it would stop this from happening. An Iranian bomb could also spur other countries in the region, such as Saudi Arabia or Turkey, to pursue their own weapons, setting off a very dangerous nuclear arms race in one of the world's most volatile regions.

Does Iran actually want to build the bomb?

Tehran's official line is that it has never tried to build or acquire nuclear weapons and that it will not do so. But in the early 2000s evidence came to light that Tehran had been building a nuclear program since the late 1980s, which included both efforts to develop peaceful nuclear energy, to which it is entitled, and a nuclear bomb. Since halting that formal program in 2003, Iran reportedly continued some research and development efforts that could help it build nuclear weapons. In addition, the country has significantly expanded its domestic nuclear industrial capacity over the past two decades.

What was the "Iran nuclear deal"? How did it constrain Iran's nuclear program?

Under a 2015 pact signed with the US, France, Germany, the UK, Russia, and China, Iran agreed to curtail its nuclear program and accept a rigorous monitoring regime in exchange for relief from economic sanctions that the US, Europe, and others had imposed on Tehran over its program. But the limitations on Iran's ability to produce material for a bomb had a caveat: they applied only for ten to 15 years. Through these and other restrictions, the international community aimed to ensure that Iran's breakout time—the time needed to accumulate enough highly enriched uranium for a nuclear weapon—would be at least 12 months, giving the international community time to respond if it looked like the Iranians were going to go for it after all.

Critics of the deal in the US and the Middle East argued that the West gave Iran too much economic relief in exchange for too few concessions on the nuclear program. They also criticized the deal for not addressing Iran's destabilizing regional behavior, support for terrorist groups, ballistic missile program, and domestic repression.

What's the current status of the nuclear deal and Iran's nuclear program?

Trump in 2018 withdrew the US from the nuclear agreement, which he had strongly criticized during his election campaign. The Trump administration instead pursued a "maximum pressure" campaign against the Islamic Republic that involved a punishing sanctions regime as well as targeted military actions, such as the assassination of Qassim Suleimani, Iran's most prominent military officer. The administration aimed to force Iran to accept even stricter terms on the nuclear front or else face economic collapse. Iran responded by systematically violating the deal's nuclear restrictions — moving it closer to a nuclear weapon than when Trump took office — as well as by escalating tensions across the Middle East. The deal still exists in theory, although both the US and Iran have by now violated almost all of its most important provisions.

Will Biden succeed in reviving the deal?

Both Washington and Tehran are committed to returning to compliance with the deal. The Biden administration seeks to salvage the agreement to constrain Iran's nuclear program and re-establish diplomacy as the core of its foreign policy. Iran needs the economic relief the deal provides. But domestic politics and mistrust in both countries have slowed down the process.

Henry Rome is Senior Analyst, Global Macro at Eurasia Group.

From Your Site Articles

- US election seen from Iran: A "rare window of opportunity" - GZERO ... ›

- Was leaving the Iran deal a good idea? - GZERO Media ›

- Why a renewed US-Iran nuclear deal is more likely than not ... ›

- Iran’s nuclear facility attacked. What happens next? - GZERO Media ›

- Iran’s nuclear facility attacked. What happens next? - GZERO Media ›

- Iran's missiles threaten entire Middle East, says journalist Robin Wright - GZERO Media ›

- The new nuclear arms race: Smarter, faster nukes - GZERO Media ›

- Nuclear weapons: more dangerous than ever? - GZERO Media ›

- Trump tariff is starting a US-China trade war - GZERO Media ›

- Trump x Khamenei nuclear duet - GZERO Media ›

More For You

FILE PHOTO: European Commissioner for Trade Maros Sefcovic and India's Trade Minister Piyush Goyal pose after signing an agreement, as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and European Council President Antonio Costa stand behind them, at the Hyderabad House in New Delhi, India, January 27, 2026.

REUTERS/Altaf Hussain/File Photo

After nearly 20 years of negotiations, the European Union and India struck a trade deal that will slash or remove tariffs from nearly 97% of all EU exports to India, and grant preferential entry to the European market for 99% of Indian products.

Most Popular

The World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters is seen in Geneva, Switzerland, January 28, 2025.

REUTERS/Denis Balibouse

Seventy-eight years after helping found the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States has formally withdrawn from the agency, following through on a pledge President Donald Trump made on his first day back in office.

Mastercard Economic Institute's Outlook 2026 explores the forces redefining global business. Tariffs, technology, and transformation define an adaptive economy for the year ahead. Expect moderate growth amid easing inflation, evolving fiscal policies, and rapid AI adoption, driving productivity. Digital transformation for SMEs and shifts in trade and consumer behavior will shape strategies worldwide. Stay ahead with insights to help navigate complexity and seize emerging opportunities. Learn more here.

- YouTube

On GZERO World, Finnish President Alexander Stubb says that Ukraine and its NATO allies are aligned on a path to a ceasefire but warns that Vladimir Putin will drag out the war, not because he thinks he’ll win… but because he knows he’ll lose.

© 2025 GZERO Media. All Rights Reserved | A Eurasia Group media company.