Seventy-eight years after helping found the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States has formally withdrawn from the agency, following through on a pledge President Donald Trump made on his first day back in office.

In a joint statement last week, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of State said the WHO had "abandoned its core mission,” and repeatedly acted against US interests. The administration pointed to what it says was the WHO’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic, its failure to adopt reforms, and an “inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence” from member states, notably China.

The withdrawal leaves the WHO without its largest funder, with serious implications for global health research, disease prevention, and pandemic preparedness. Paired with the dismantling of USAID, it also marks a further erosion of America’s traditional soft power, long deployed through multilateral health efforts such as supporting health systems and disease-campaigning initiatives.

What does the WHO do? Since 1948, the WHO has served as the coordinating health authority for the United Nations’ 194 member states. Its primary functions include developing and monitoring international health standards – such as the International Classification of Diseases – and coordinating global responses to disease outbreaks, including COVID-19, Ebola, and Zika.

Over the decades, the WHO has achieved major successes, including campaigns to eliminate river blindness – a parasitic infection that affected hundreds of thousands in Africa and Latin America – and to eradicate smallpox worldwide. But it has also faced sustained criticism. Detractors accused it of reacting too slowly to the global AIDS and HIV epidemic in the 1980s, and failing to contain the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

The agency has been accused of prioritizing politics over health at times, pointing to, for example, its refusal to grant Taiwan observer status in deference to Beijing’s “One China” policy, a move that limited the island’s access to the WHO’s disease control programs. Trump himself has repeatedly charged that the WHO’s director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, hid China’s missteps at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, which the WHO denies.

The US withdrawal by the numbers. Between 2024 and 2025, the US pledged $958 million – roughly 15% of the agency’s $6.5 billion annual budget. But Washington hasn’t fully paid its tab, though, according to the WHO. The US still owes roughly $260 million in unpaid dues, a charge HHS disputes.

Beyond funding, Washington has also contributed data, personnel, and technical leadership. According to a HHS news release, all US staff and contractors assigned to or embedded with the WHO have been recalled from all offices worldwide. Hundreds of US engagements have been suspended or discontinued, and the US will no longer engage in WHO-sponsored committees, leadership bodies, or technical working groups.

What this means for public health. Low- and middle-income countries – especially in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia – rely heavily on WHO-coordinated programs for HIV/AIDS, maternal and child health, tuberculosis, and malaria control. But the fallout won’t be limited to poorer countries.

According to Dr. Judd Walson, chair of international health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the effects “will be a slow bleed” over the coming years, leaving even wealthy countries less aware of emerging disease threats.

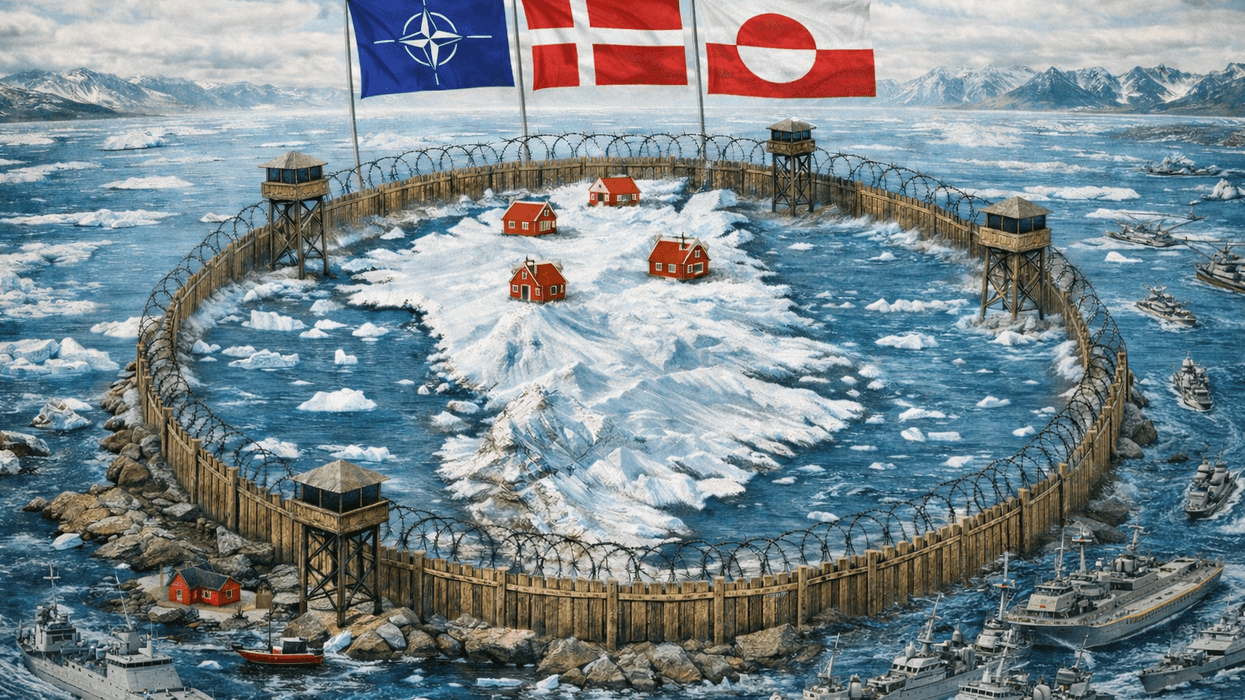

Who will fill the gap? For an administration that’s accused the WHO of favoring China, the US departure carried a certain irony. Pulling out could boost Beijing’s influence inside the agency. In May 2025, China pledged to increase its voluntary contributions to $500 million over the next five years, positioning itself as the WHO’s new biggest funder and most powerful member.

That shift could further steer global health priorities in ways that serve Beijing’s interests –from promoting reliance on its pharmaceutical industry to giving it greater access to global health data. Combined with Washington’s cutbacks to USAID, it also creates an opening for Beijing to increase its soft power, cultivating goodwill through so-called “vaccine diplomacy” and other initiatives in countries struggling with unmet health needs.

Could other countries follow – or form an alternative? Last spring, Argentina announced it would withdraw from the WHO in line with US policy. Though its membership dues are modest – $8 million in 2024 – it could encourage other countries to follow suit.

Washington’s exit from the WHO comes as Trump launches a “Board of Peace” which has so far garnered 35 members. Some world leaders – including US allies in Western Europe – signaled caution that the body could rival the UN. If Board of Peace members were to leave the WHO along with the US and Argentina, the agency could see further reductions in funding, credibility, and its ability to meet global health challenges.

But the WHO could also see new partnerships. On Friday, California announced that it would become the first US state to join the WHO’s Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, a network of more than 360 technical institutions that detect, verify, assess, and respond to emerging public health threats. In a direct rebuke of the president, California Governor Gavin Newsom said, the Trump administration’s “withdrawal from WHO is a reckless decision that will hurt all Californians and Americans.”

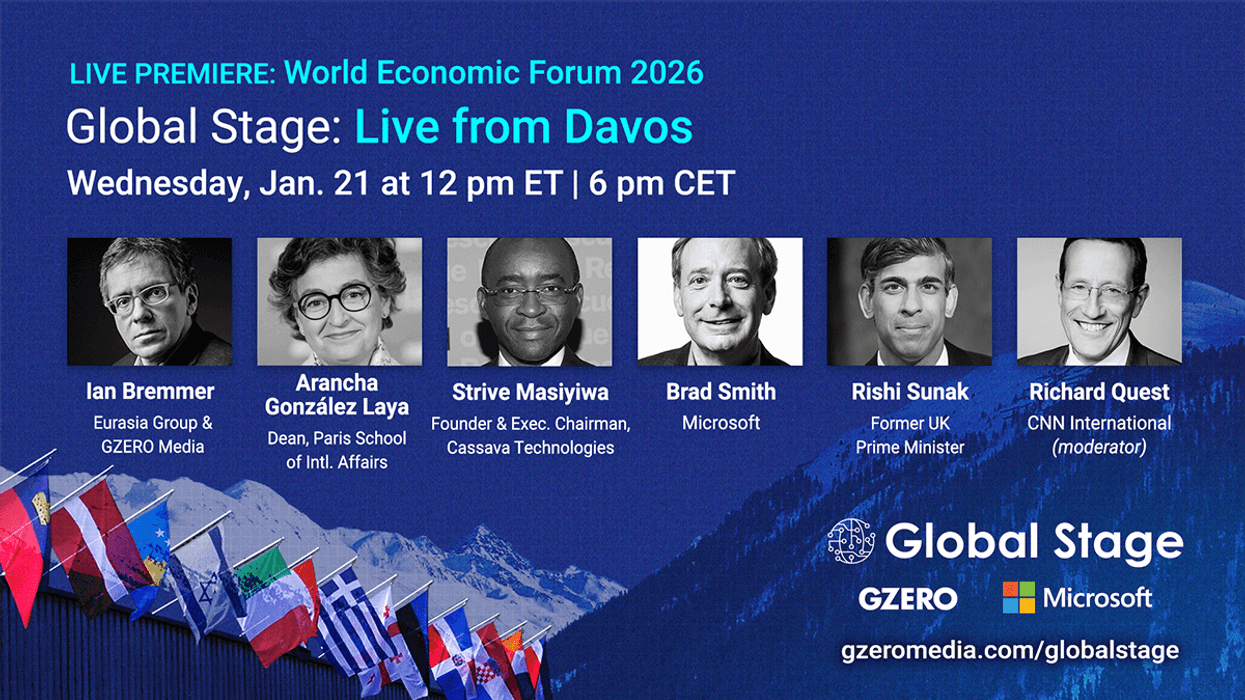

While California can’t become a full member of the WHO, its decision highlights fractures within the US and its leadership on the global stage, with individual states charting their own courses in opposition to Washington’s broader agenda. It’s the kind of fragmentation that GZERO’s founder, Ian Bremmer, often cites as an emblem of a “G-Zero world,” where no single country, or group of countries, can provide global leadership. With the US out, who steps up to lead global health? For now, who knows.