Welcome to this special edition of Signal, in which we'll look at why everything is getting more expensive these days, how inflation is affecting other global issues, and what — if anything — can be done about rising prices while the pandemic keeps raging. This edition is part of a joint project between GZERO Media and Citi Private Bank called "Living Beyond Borders."

Thank you for reading.

The Signalistas

How long will COVID-fueled inflation last?

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos SantamariaEverybody's talking about inflation these days. Rising prices are affecting people from all walks of life, all around the world.

In the US, buying a used car now costs on average 45 percent more than it did in January. Europeans are bracing for a tough winter with soaring natural gas prices that come at the worst possible time.

Asian investors mentioned the word "inflation" on calls this quarter the most times since 2003, when the SARS epidemic battered China's economy. In Lebanon, whose annual rate of inflation is now the world's highest, surpassing Venezuela and Zimbabwe, most people buy local not to support local businesses but rather because they can't afford imports.

Inflation, however, isn't always bad, and is actually a sign of a healthy economy as long as it stays around an annual 1.5-2 percent. But now in most countries it's creeping up too much due to the economic fallout from the ongoing pandemic.

Eighteen months later, demand is booming. Consumers have a lot more cash burning in their wallets than a year ago because they didn't spend much at all in 2020. Businesses too are humming again, and need energy and raw materials to keep their plants running and products delivered on time.

But the real problem is on the supply side. Persistent COVID-related disruptions to supply chains mean there's simply not enough stuff, or you can't get it as fast as you'd like. When you can, it's gotten more expensive, and as the added costs get tacked on, the price of everything goes up.

For instance, a new car has become a luxury all around the world due to a global shortage of semiconductors. If you're in the market for a new house or want to build a factory, prices are going through the roof and projects are getting delayed because building materials — particularly those sourced from overseas, which is the case for most countries — are scarce and will take longer to acquire.

Meanwhile, inflation is fast becoming a global political headache.

Most Brazilians blame President Jair Bolsonaro for the rise in their cost of living. In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has already fired two central bank governors since the pandemic began because they opposed the big stimulus spending he needs to stay popular while the country's currency plummets and inflation remains sky-high. Tunisia's President Kais Saied is also feeling the heat after having had little success persuading businesses to lower their surging prices.

US President Joe Biden's ambitious plans to expand the country's social safety net could get tanked by moderate Democrats who fear investing $3.5 trillion now will spur more inflation just as the economy is stabilizing, and have Republicans on their side. But there's also a bipartisan generational divide: a survey commissioned by the Federal Reserve shows that retiring boomers — many still traumatized by the 1970s "stagflation" period of low economic growth coupled with double-digit inflation — are a lot more worried about inflation than younger Americans.

Still, there's little that can be done right now to fix the problem from the supply side. Central banks raising interest rates could temper demand, removing some of the pressure on prices, but it won't move the needle on inflation from messed-up supply chains while COVID lingers.

Moreover, when governments do intervene on supply by restricting exports that other countries need, for instance Argentinian beef or Russian wheat, it makes things worse because such distortions may provide some short-term relief but in the long term only further increase demand — and therefore costs for everyone. (This, along with several climate-related droughts, explains why global food prices are now rising at the highest pace since 2007, when food riots sparked a wave of social unrest across parts of Africa and Asia.)

Inflation clearly wasn't a blip, but most economists say we shouldn't panic (yet). Inflation, they say, will likely return to target levels once the pandemic is behind us. But as long as COVID stays, so will its disruptor effect on all economies. So perhaps the way out of today's inflation is to get vaccines everywhere.

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

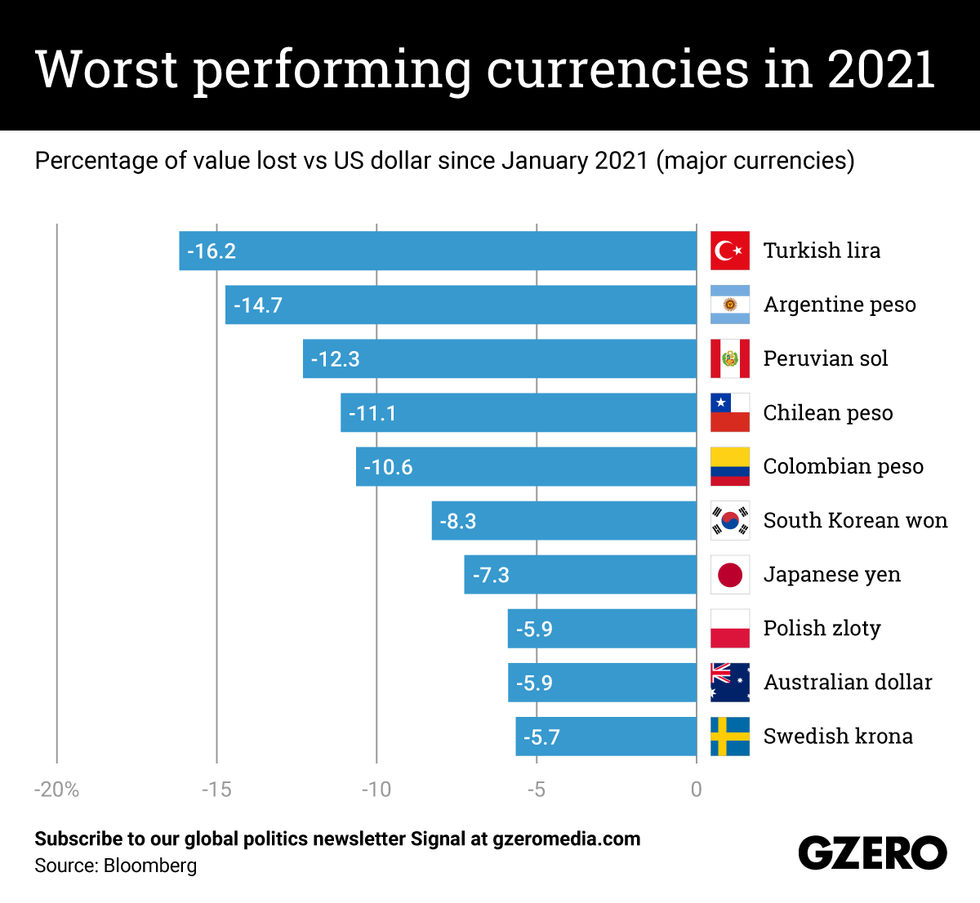

Gabrielle DebinskiThe pandemic brought the global economy to its knees, disrupting supply chains and causing a surge in unemployment. The economic volatility also sent many major currencies into a tailspin. While already-weak economies have been hit hardest by inflation, many medium and high-income countries have also seen their currencies depreciate over the past 18 months amid protracted lockdowns, border closures and supply chain constraints. We take a look at which major currencies have depreciated the most in 2021 when measured against the US dollar.

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Private Bank

Citi Private BankJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

What We're Watching: Inflation's impact on energy, climate, and… pasta

GZERO Media

GZERO MediaEnergy price surge + winter = ? Natural gas prices are at all-time highs in Europe. In the US, they've gone to a 14-year peak. With demand from post-COVID economies outstripping supply, and winter coming, bills for heating and electricity could soar — and drive up inflation on both continents. Fears about natural gas have, in turn, caused a run in oil markets, driving crude prices to three-year highs as well. Meanwhile, restrictions on using coal have contributed to blackouts in China, causing some exporting factories there to slow production just ahead of Christmas season, when demand for Chinese-made consumer goods soars. More holiday demand chasing fewer gadgets and clothes would mean higher prices. And then of course there's the question of how to tackle inflation while promoting climate change policies that are meant to reduce emissions…

Will inflation affect climate goals? In the lead-up to COP26, a big UN climate summit, governments and corporations are questioning whether a hasty transition to green policies might further increase prices of things like air travel, contributing to the inflation problem. The European Central Bank says that slashing carbon emissions to net zero by 2050 could have unpredictable impacts on inflation, but ECB President Christine Lagarde says it's "the least of our worries, " and will allow inflation to rise beyond its usual 2 percent target while the bloc meets its climate goals. After all, inflation is not the only cause of the current spike in food prices, which are also driven by climate-change induced bad weather destroying farmers' crops in many places. But as governments push for decarbonization, many industries will have to change how they make things, likely driving up costs. Still, large economies like the US, the UK, and China seem committed to the move to a more sustainable world, saying that boosting energy efficiency could lower household heating bills, while more fuel-efficient vehicles could cut consumer costs in the long term.

Do you like pasta? We like it too, and we're not alone. It's hugely popular around the world – from Brazil and Chile to the Philippines, to South Africa and Tunisia, as well as across Europe and the US. Its popularity isn't a mystery. It's easy to find, easy to make, goes with lots of other types of food, and is (usually) inexpensive. But to prepare all that pasta, we need semolina, the flour most often used to make many forms of noodles. And to make semolina, we need durum wheat. But extremely hot and dry weather will cut the export of durum wheat from Canada, the world's lead supplier, by almost a third. Add a lousy wheat crop in Italy, where the consumption of pasta is not unknown, and you've got supply cuts, and therefore higher prices, for one of the world's most popular foods and a dish that low-income people can usually afford. The price of durum wheat is now up 90 percent.The Graphic Truth

Carlos Santamaria

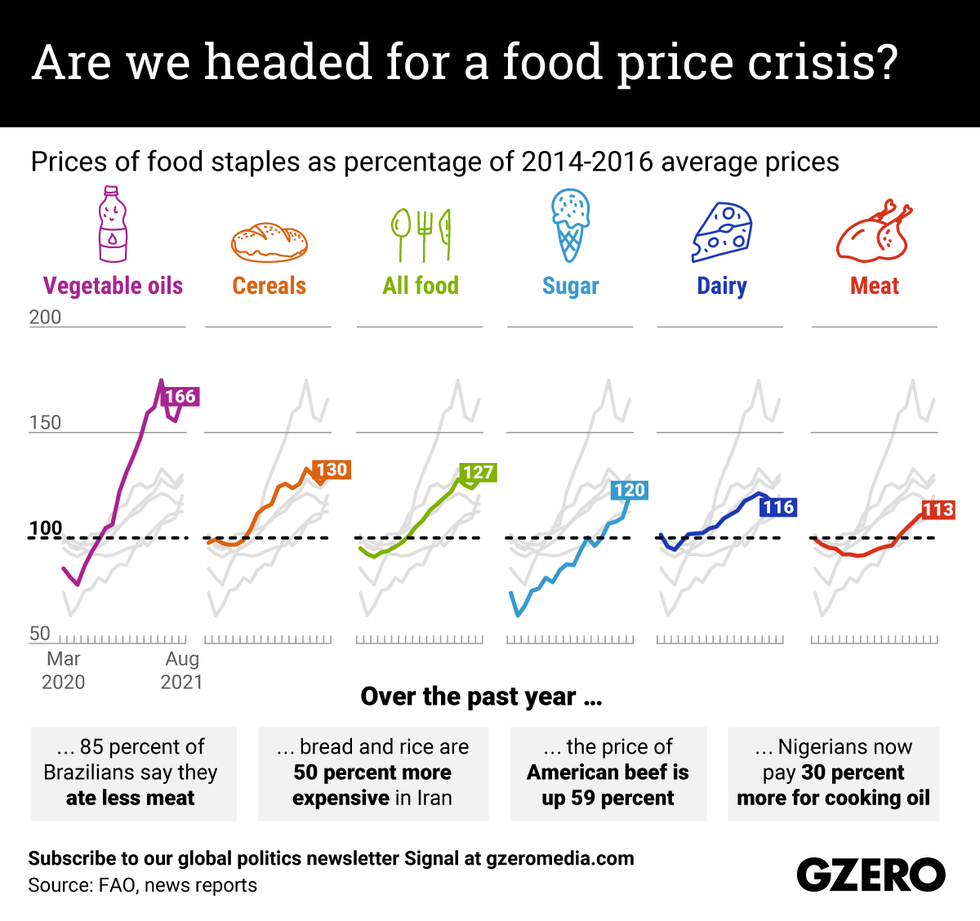

Carlos SantamariaGlobal food prices have jumped by one-third since a year ago, as a result of pandemic- and climate-related supply chain disruptions as well as export restrictions. While the situation isn't (yet) as bad as in 2007-2008, when sharp increases in food prices triggered civil unrest across many parts of the world, the trend isn't a good one. Food price inflation and, in more extreme cases, the risk of famine will only exacerbate the challenges of economic collapse and mass unemployment left behind by COVID. We take a look at how the global prices of five key food products have changed since the pandemic began.

Podcast: Inflation, interest rates, and economic recovery

When the pandemic hit in full force in the US, the government had to act quickly to keep the economy afloat. One major thing that the Federal Reserve did was lower interest rates to zero. That helped money keep flowing and borrowing rates low on things like mortgages, cars, and other things Americans needed. The danger in juicing the economy this way, however, is that inflation could go up, and higher consumer prices could end up hurting our wallets. How does the government strike the right balance? Listen to more about the US recovery, the international picture, and what could come next in this podcast featuring Robert Kahn, director of Global Strategy and Global Macro at Eurasia Group; David Bailin, CIO and Global Head of Investments at Citi Global Wealth; and Steven Wieting, Chief Investment Strategist and Chief Economist at Citi Global Wealth. Moderated by Caitlin Dean, head of Geostrategy at Eurasia Group.

Inflation quiz!

1. Which European country experienced the highest recorded rate of hyperinflation?

A. Hungary

B. Poland

C. Germany

2. A loaf of bread cost how many Zimbabwean dollars in 2009?

A. One billion

B. One trillion

C. One quatrillion

3. In 1949, US President Harry Truman was feeling the pinch of post-war inflation. What did he do about it?

A. Made the Fed raise interest rates

B. Cut spending

C. Bumped his salary up

Hard Numbers: ECB remains calm for now, Nigerians in poverty, Brazilian instability, Japanese deflation

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle Debinski10: Inflation in the European Union reached a 10-year high in recent weeks, fueled largely by rising energy costs. While some observers are sounding the alarm, the European Central Bank has remained calm(ish), saying that inflation will likely taper off early next year as production bottlenecks stabilize and the pandemic (here's hoping) recedes for good.

45.2: The World Bank predicts that by next year, 45.2 percent of Nigerians (more than 95 million people) will be living in poverty as a result of inflation caused by supply chain disruptions and food price rises fueled by the pandemic. That's a jump of five percentage points from 2019 levels.

4: Brazil's central bank has raised its reference interest rate four times since March in a bid to curb rising inflation, which reached 10 percent annually last month. In a region traumatized by years of financial volatility, President Jair Bolsonaro is already facing political backlash and a tough reelection bid next year.

-0.3: Japan is the only major economy to have experienced deflation during the pandemic, with prices dropping 0.3 percent from the previous year in recent months. Tokyo has long been trying to boost consumer spending and demand, which have lagged in part because of Japan's aging population.

Answers

1. A — Toward the middle of 1947, Hungary's inflation rate had reached, we kid you not, 13 quatrillion percent. That meant prices doubled every 16 hours, and the central bank even printed a one hundred quintillion (16 zeros) pengo bill that was worth a lot less by the time it left the mint.

2. B — Everyone was a trillionaire in Zimbabwe those days, except that it didn't buy you much, since the economy was a shambles because Robert Mugabe kept printing money like there was no tomorrow.

3. C — Four years after World War II, Truman was still making only $75,000 per year, the set pay rate for US presidents since 1909. During his second term, he convinced Congress to raise it to $100,000 (now it's $400,000).

This edition of Signal was written by Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. Art by Jess Frampton and Paige Fusco, graphics by Gabriella Turrisi.