Silicon Valley has wandered into a political and ethical minefield. As digital technologies have become pervasive, they’ve also become strategically important: victory on the battlefield will increasingly depend as much on the power of a military’s servers, or its ability to harness emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, as it does on who has bigger guns. As the line between the data center and the combat zone becomes blurred, previously simple decisions for tech companies – like whether to build a new computer system for the Pentagon – have become a lot more sensitive.

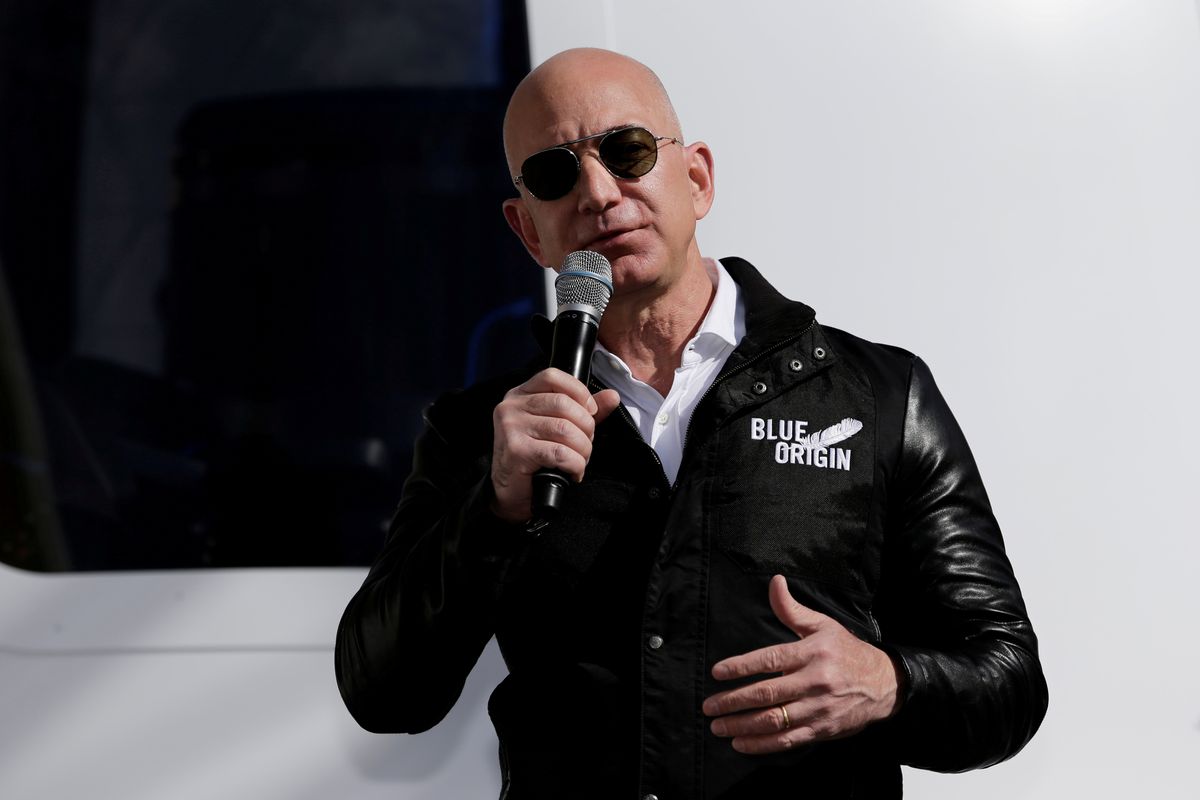

Individual US tech giants are making different calculations about how to approach the politically fraught topic of working with the military. Last week,we wrote about Google’s decision to withdraw from bidding on a $10 billion Pentagon IT contract. This week, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos took a different tack: telling the crowd at a Wired event in San Francisco that “if big tech companies are going to turn their back on the Department of Defense, this country is in trouble.”

Here are the different lenses Bezos, Google CEO Sundar Pichai, and other tech executives are applying to the problem as they decide whether and how to engage.

Different internal politics: Where a company comes from and whom it employs are bound to influence the decision about whether to get involved in military work. Google’s founders were idealistic Stanford grad students who included the commandment “don’t be evil” in the company’s initial public offering prospectus. Amazon, given its need for warehouses and shipping centers, employs a larger proportion of blue-collar workers, who may be more open to military cooperation than liberal-leaning Silicon Valley types.

Different calculations: Amazon may have seen bidding for the Pentagon deal as a solid trade: The company is already considered to be a leading contender thanks in part to an earlier project it worked on for the CIA, while Google was more of a long shot. Google is considering re-entering China’s search market after an eight-year hiatus, and may want to avoid appearing too close to the US government.

Different ideas about how best to address ethical challenges created by tech:Tech companies have a choice when deciding how best to respond to the ethical challenges posed by technology. Google’s ethical principles bar the company from getting involved in any project involving weapons, or where its artificial intelligence technology is likely cause human harm. Amazon may feel comfortable taking a different approach in this case. As the lines between civilian and military technology continue to blur, companies will increasingly have to choose between withholding their technology from controversial projects or working from the inside to try to shape how their technologies are deployed. Reasonable people can disagree on which approach is likely to lead to more ethical outcomes. These hard questions and tradeoffs are unlikely to go away anytime soon.