Key to President Joe Biden’s agenda, the Inflation Reduction Act, which was signed into law on Aug. 15, 2022, contains about $400 billion in new spending and tax breaks aimed at jumpstarting the transition to a low-carbon economy in the US. Alongside the Chips+ Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the IRA also aims to reinvigorate US manufacturing to allow the country to better compete with China.

Biden’s embrace of industrial policy to achieve these aims has been controversial because of its expense and the concerns of trading partners that the massive government assistance gives US firms an unfair advantage. So, is the bet paying off? We sat down with Eurasia Group expert Milo McBride to ask him what the IRA has achieved in its first year.

What are some tangible impacts of the new legislation?

The IRA has already prompted investments of about $270 billion in the power sector, $50 billion in electric vehicle supply chains, and smaller yet significant contributions in other sectors. If the policy continues as planned, analysts at Goldman Sachs expect it to generate about $3 trillion of investment by the early 2030s – underscoring its potential to integrate EVs and other clean energy systems into everyday American lives. Specific projects to highlight include the Battery Belt, a comprehensive EV and battery hub that spans from Michigan to Missouri, and the construction of enough solar manufacturing facilities to eventually produce the systems needed to meet much of the nation’s solar energy demands.

Is it meeting goals?

While the IRA is a step in the right direction for the Biden administration’s low-carbon energy agenda, it will fall short of delivering on US climate pledges. The IRA’s green industrial policy is an incentives- or “carrots”-based approach that provides subsidies for clean alternatives but doesn’t impose penalties on carbon emissions. The US has outlined goals to reduce its carbon emissions by 52% by 2030 from 2005 levels, and with the IRA, it will achieve reductions of somewhere between 32% and 42%, according to the Rhodium Group.

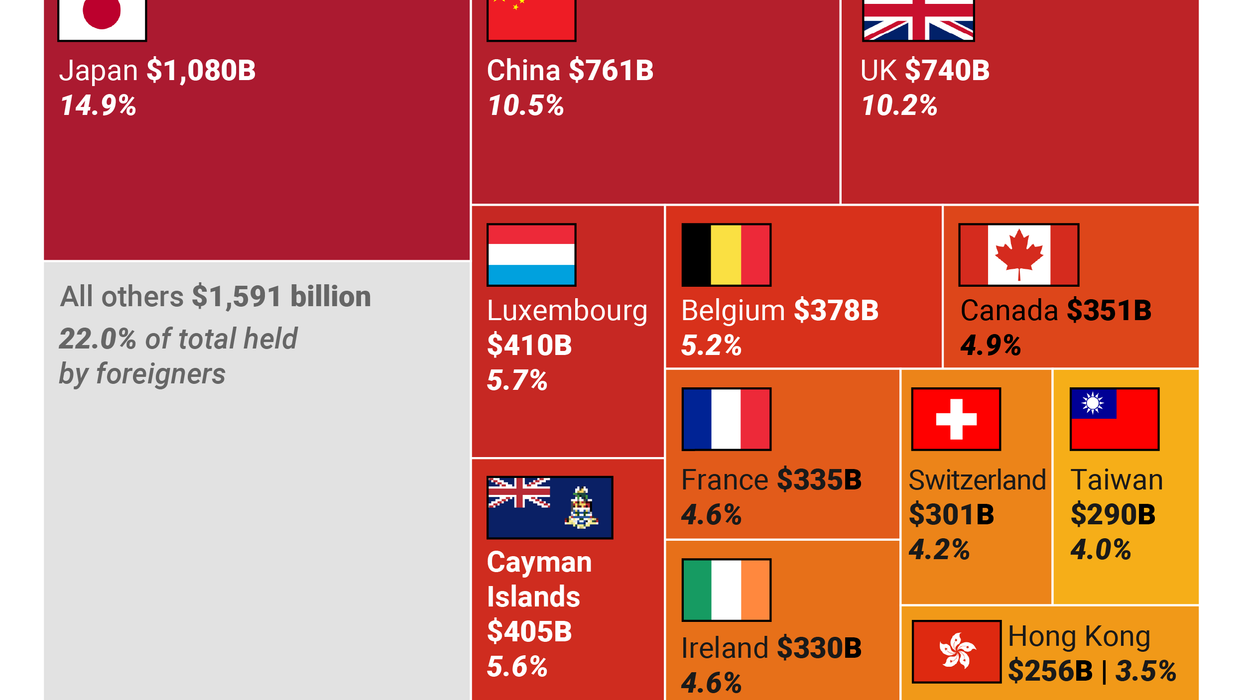

Scaling up US manufacturing is a massive endeavor that could undermine the goal of building a domestically resilient supply chain in the short term. For example, constructing battery gigafactories can be accomplished in a matter of years, but developing mines to produce the critical minerals needed by those factories may take a decade. Over the next couple of years, this dynamic will increase US reliance on imports, some of which will come from allies but also potentially from China.

What are the biggest domestic challenges?

There are myriad obstacles. The scale of renewables capacity being built requires an expansion of the electrical grid to transmit wind- and solar-generated electricity to areas of high energy demand. Yet the last major transmission line built in the US needed an astounding 15 years to secure the needed approvals, a bureaucratic problem that policymakers in Washington are unlikely to solve anytime soon. Similarly, while most forecasts expect EVs to account for about half of US car sales by 2030, this growth will require a massive expansion of public EV charging infrastructure. Under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the government is disbursing $7.5 billion to the states to build public charging stations, but the rollout will be an enormous undertaking.

There is also concern about the availability of the workers needed to drive the energy transition at a time of record low unemployment. Low-skilled labor is needed to perform tasks such as the installation of solar panels, but high-skilled workers are also needed to build complex machinery like battery or solar components, which can require expertise in advanced robotics systems or the scientific intricacies of these components.

What are the political factors to keep in mind?

Although the IRA has led to the creation of a disproportionate number of green jobs in red states, Republicans in Washington remain strongly opposed to the legislation. Given this reality, the success of the IRA will hinge on the 2024 presidential election. If Biden or another Democrat wins, they will keep the IRA intact while advancing environmental regulations and furthering green energy partnerships with allies. However, if Donald Trump or another Republican wins, the outlook is less clear. In a second term, Trump could take a wrecking ball to his predecessor’s achievements (as in his first term). That said, Trump, in his uniquely unpredictable way, could decide he likes Biden’s industrial nationalism and try to take credit for it by rebranding it in his own image.

If the Republicans decide to repeal the IRA, certain facets of the policy will be more at risk than others. At the top of this agenda is gutting the massive budget that the IRA gives the Department of Energy and the Environmental Protection Agency, while also removing the tax credits that are used to subsidize new renewable energy projects. However, other policies such as subsidies for carbon capture and clean energy manufacturing would face less risk, as damaging US industry would be politically unpalatable, especially for an America First president. By January 2025, when the next presidential term begins, many of the factories that the IRA helped build would either be operational or under construction. Withdrawing the subsidies or sunsetting tax incentives that made them economically viable would risk a backlash from industry and investors.

How has this signature piece of industrial policy affected US relations with trading partners?

Initially, the protectionism enshrined in the IRA raised eyebrows among US allies, but as of today, it hasn’t produced a rift among trading partners. The Biden administration has sought to address initial frustrations with a series of clean-tech trade deals or partnerships with Canada, Japan, India, Australia (and likely the EU soon). It has also offered generous subsidies to Korean firms, including the energy department’s recent $9 billion loan to SK Innovation, a battery manufacturer that supplies Ford Motors.

Similarly, the IRA appears unlikely to trigger a subsidy race that would strain the finances of governments around the world (just Canada has emulated the US approach). The EU, for example, has prioritized regulatory reform alongside more modest subsidies to encourage greater investment in green industries.

How has Canada responded?

Though Canadian miners stand to benefit from increased US demand for essential critical minerals such as lithium, nickel, and graphite, policymakers don’t want to renounce the opportunity to participate in more lucrative segments of the green industry such as battery manufacturing. As a result, Ottawa’s 2023 budget mirrored many of the IRA’s tax credits and officials have pledged enormous sums to woo investments away from their larger neighbor. For example, the Canadian government has pledged $CA15 billion and $CA16 billion in subsidies for battery factories for Volkswagen and Stellantis, respectively, well above what the US government has pledged to such facilities.

While this competition is unlikely to disrupt the political and security-based alliances between the two nations, it will create challenges for Canadian policymakers trying to match the US’s fiscal firepower. In time, they will probably recognize the limits of this approach and focus more on promoting those projects Canada has already launched over trying to attract new ones.

Edited by Jonathan House, Senior Editor at Eurasia Group