Welcome to this special edition of Signal, sponsored by Citi Private Bank, where we'll look at how the COVID-19 crisis might permanently change the global balance of power. This edition is part of a new joint project between GZERO Media and Citi called "Living Beyond Borders."

After COVID: The United States vs China

Willis Sparks

Willis SparksChina and the United States — geopolitical challenger and defending champion— were on a collision course long before COVID-19 took hold. The rivalry has been building for a generation and has intensified in the past three years.

China's President Xi Jinping grabbed Washington's attention in 2017 when he announced a "new era" in which China would move "closer to [global] center stage" and offer "a new option for other countries." That is, an alternative to US leadership in the world. President Donald Trump upped the ante with a declaration of trade war on China.

Then came the novel coronavirus, which began in China and has inflicted its worst damage in the US. Each government has pointed fingers at the other to deflect criticism of its own COVID failings.

How might the pandemic, and its aftermath, alter the rivalry between the world's two largest economies?

China's COVID initiative – In some ways, the coronavirus has boosted China's international image. Its success in containing the virus, the relative COVID chaos in the US and Europe, and China's willingness to help struggling governments, even in Europe, with critical medical supplies and cash, has allowed Beijing to claim a crisis leadership role that once fell to Washington. Meanwhile, China's economic growth looks to be less affected by the pandemic, as the IMF predicts Chinese GDP will continue to expand this year, even while America's contracts.

Continuing US advantages – China's rise doesn't imply a post-COVID US decline. In fact, though COVID has wreaked political and economic havoc in the United States, and government dysfunction is a large and growing problem, the US has lasting advantages that gives it staying power as a central international actor.

The US has long been the world's number one food exporter, and game-changing innovations in energy production have made the US the world's top oil producer. In addition, dollar dominance won't last forever, but today's governments still need greenbacks, allowing the US to continue borrowing as no other country can.

But the biggest post-COVID US advantage is the current dominance of its tech companies. That's why technology is the arena where the post-COVID US-China rivalry will become most intense.

The tech battlefield – Today, 11 of the world's 13 largest internet companies are US-based, and the US produces more of the tech startups that will drive innovation in the AI and other cutting-edge technologies that will soon dominate global economic development. COVID enhances those US advantages, because contact tracing, immunity passports, and remote work, enabled by new technologies that US companies have a jump on, are now more important.

Chinese companies, with priority backing from their government, are working in all these same areas and will continue to make progress, and China's government is going all in to make China a technology superpower over the next decade.

Which country will assume the lead in the race for 5G? Will one country gain an insurmountable advantage that allows its regulators to write the rules that govern these technologies? That will be the US-China battleground where the stakes are highest.

The election wildcard – The outcome of the US elections in November will also mark a turning point in US-China relations. On the one hand, no matter who wins, Washington and Beijing will remain on a collision course: opposition to some of China's trade practices and the ways it uses data to limit individual freedom are rare issues on which Democrats and Republicans agree. And the US public's distrust of China is at its highest level since polling on the issue began 15 years ago.

If President Trump wins re-election, he's likely to continue the current aggressive unilateral US approach on trade and intellectual property questions. But a President Biden would likely be much more inclined to coordinate pressure on China with likeminded traditional allies in Europe and Asia. That's why Chinese officials may have more to fear from Biden's alliance-building than from Trump's more impulsive go-it-alone approach. If so, a Biden win might ease the tone of the rivalry in the near-term, but broaden and deepen its substance over time.

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

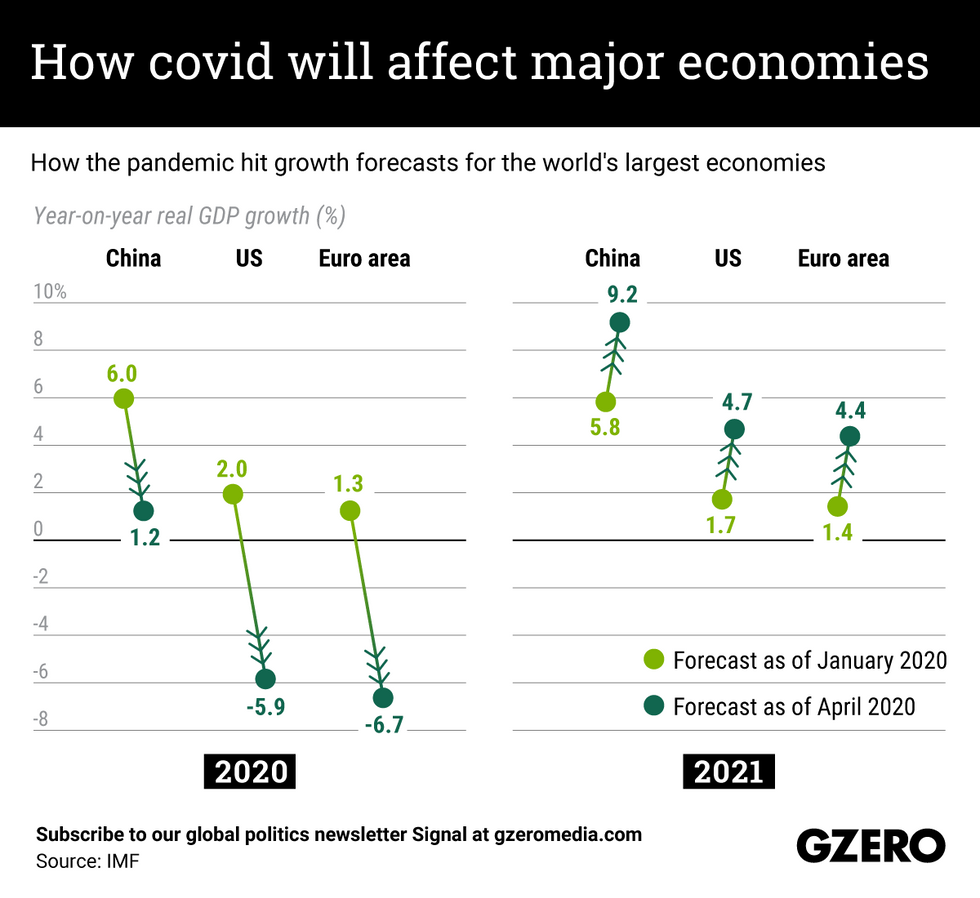

Gabrielle DebinskiLockdowns and social distancing restrictions have brought much of the global economy to a halt over the past few months, causing unprecedented levels of joblessness and throwing international commerce into disarray. As the virus continued to spread throughout the first quarter of the year (there are now cases in at least 188 countries and territories) the IMF updated its original growth forecast for 2020, and the predictions are grim. The world's largest economies – China, the US and the Euro area – are set to experience massive year-on-year contraction. But there's a silver lining: The IMF says that there are signs of a promising economic recovery for these economic regions in 2021. Here's a look at the numbers.

No Ordinary Recession, No Ordinary Recovery

Citi Private Bank

Citi Private BankAs a new economic and market cycle gets underway, we release our Mid-Year Outlook, 'From Fear to Prosperity: Investing in a New Economic Cycle'.

We expect a more rapid rebound than many others do. But just as the COVID-19 collapse is no ordinary recession, this will be no ordinary recovery. We believe the new cycle calls for a new approach to investing. While beaten-down bargains are less widespread, we identify markets with greater rebound potential. We also update long-term asset class return estimates and outline important allocation shifts needed to seek diversification in today's world of very low interest rates.

Read the full report, learn more about key themes in the report, and view related videos.

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiThe global race is on to develop a vaccine against COVID-19. While it usually takes many years to develop and widely distribute vaccines, scientists around the world are now trying to get one ready within the next year — an unprecedented time frame. The race has generated fierce competition among countries, as everyone wants to develop a vaccine on their home turf first, not only for prestige, but also to get their citizens at the front of the line for the shots when they are available. Still, while the scientific world is now rife with geopolitical rivalries over the COVID-19 vaccine, there's also a lot of international collaboration going on behind the scenes. Here's a look at the vaccines currently in Phase II of the clinical trial process, meaning they are being tested on hundreds of people of various age groups to determine their effectiveness and safety. If they pass this stage they move to wider testing in Phase III, the final step before approval.

GZERO World Podcast: The upside after coronavirus

The world is in crisis right now. Global health experts are racing to end the worst pandemic in more than a century, while governments and economists are scrambling to stabilize markets and get industries back to work again. But is there room for optimism about the future?

In this special edition of the GZERO World podcast, produced in partnership with Citi Private Bank, Eurasia Group strategy head Meredith Sumpter moderates a chat with Eurasia Group president Ian Bremmer and Citi Private Bank's Chief Investment Officer David Bailin. If political and financial leaders make the right decisions, they say, 2020 could mark a major turning point in addressing the challenges of inequality, sustainability, and a fragmenting world order. Listen to the podcast here.

What We're Watching: How the pandemic affects Europe, emerging markets, and populist leaders

Alex Kliment

Alex KlimentHow does Europe fit in? Even before the pandemic struck, Europe was struggling to redefine its role in a world where the US is a more fickle ally and China is a more assertive challenger. In particular, Brussels has been trying to style itself as a global leader in the responsible regulation of tech companies. In some ways, the pandemic has boosted those ambitions: as governments use contact tracing apps and facial recognition to help stop the spread, Brussels regulators are paying close attention. They're also cracking down on misinformation about the coronavirus. But first the EU has a bigger challenge to address. Faced with the worst economic crisis in its history, it has to prove to a rising chorus of (euro)skeptics that it is capable of cushioning the blow, and equitably rebooting economic growth across the Union. The European Commission, fearing an economic and even political fragmentation of the bloc, has unveiled an unprecedented 750 billion euro coronavirus rescue plan -- but not all member states are in favor.

Emerging markets on the ropes: While the world's largest economies duke it out for power in the post-pandemic world, many of the world's developing economies will still be digging out of the most severe shock they have experienced in generations. Faced with a quadruple hit of local economic shutdowns, collapsing demand for their exports, evaporating remittance flows, and vanishing tourism, many cash-strapped and highly-indebted developing economies are on the ropes. Poverty rates are set to rise significantly – the UN warns that as many as 500 million people could plunge below the poverty line as a result of the pandemic. In Latin America alone, a quarter of the 100 million people who came out of poverty over the past twenty years could fall right back. What's more, as the pandemic accelerates international firms' embrace of automation – robots don't get sick and can work wherever you ask them to – emerging markets that depend on manufactured exports could see millions of jobs vanish permanently. In all, the first two decades of the 21st century saw a rapid rise in the economic clout and living standards of lower-income countries. The next decade will be spent largely picking up the post-pandemic pieces.

How populism fares in all of this: One of the major trends in global politics in recent years has been the rise of populist nationalists who swept to power on promises to break the old political establishment, reverse the tide of globalization, and do more to put their countries "first." So how are they doing amid the pandemic? In some cases their innate distrust of traditional experts and weakening of state institutions has contributed to the spread of the disease: there's a reason that the US and Brazil have the two highest case counts and are among the leaders in deaths per 100,000 people. But the spread of a deadly disease across borders is also perfect fodder for leaders – like, say, Hungary's Viktor Orban, or the Law and Justice party in Poland – who argue that less economic and cultural integration is safer for everyone. How Poland's current leaders fare in an upcoming election may be a bellwether. More broadly, populism grows easily in situations of economic crisis and income inequality. The pandemic has served up both in spades. We are watching to see where populists are able to capitalize.

Hard Numbers: Vietnam on the rise, China delays developing countries' debt, Americans wary of Chinese power, European woes

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle Debinski5: At a time when most national economies are reeling, one country is faring very well. After responding to the pandemic early and quickly, Vietnam, one of the fastest growing economies in the world, has recorded no deaths from COVID-19 and is even slated to grow by 5 percent this year. Meanwhile, large economies like the US, Japan, and Australia have officially entered recessions.

77: The Chinese government has agreed to temporarily delay debt repayment for at least 77 developing countries as part of a Group of 20 nations initiative aimed at alleviating low-income countries' economic pain amid the pandemic. This is on top of an earlier commitment by President Xi Jinping to give low-income countries around $2 billion to help fight the pandemic and recover afterwards. Details about the allocation of that money, however, are still murky.

50: Exactly half of Americans – 50 percent – believe that China's international standing will wane after the pandemic as a result of its dodgy handling of the initial outbreak, according to a new Pew study. Many Americans (62 percent) now agree with the statement that Chinese power is a major threat to US interests, a 14 point increase since the question was last posed in 2018.

14: The pandemic's impact on growth will be biggest in Europe, according to the OECD, a group of advanced countries. Spain, France, Italy and the UK will suffer most, with GDP in each contracting by at least 14 percent from the previous year. That's a collapse nearly twice as big as the projection for the global economy, which is set to shrink by 7.6 percent this year.

Follow us on Twitter and Instagram. If a friend sent you this email, you can subscribe here.

This edition of Signal was written by Willis Sparks, Gabrielle Debinski, and Alex Kliment. The graphics were made by Ari Winkleman and Gabriella Turrisi. Spiritual counsel from a duck in New Zealand that once drank a beer and fought a dog.