You might have noticed shelves at your local CVS look a little more bare than usual. Maybe you ordered a couch (or a Peloton!) in June and are still sitting on the floor, waiting for it to get delivered. (Get up. At least sit on a box.) And if you follow the news, surely you’ve been urged to get an early start on your holiday shopping lest your kids wake up to a big pile of nothing come Christmas morning.

A near empty shelf at a Target in Houston, Texas on October 25. (Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

A near empty shelf at a Target in Houston, Texas on October 25. (Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

What’s going on?

The short answer is that the Covid-19 pandemic has put global supply chains under extraordinary strain, with impact throughout the US economy. This disruption has taken place at every link of the chain, from the Asian factories that manufacture and assemble goods and the ships that transport them, to the US ports where they wait to be unloaded and the trucks that are supposed to get them to warehouses and retailers.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

As a result, virtually all industries and products—ranging from toilet paper and coffee to gym equipment and lumber—are experiencing delivery delays, shortages, and inflation.

These issues are affecting not just consumer goods, but also the raw materials and energy to produce them, critical intermediate components like semiconductors, shipping containers and truck chassis, and skilled logistics, transportation and distribution workers (including seamen, dockworkers, and drivers).

“For instance, a new car has become a luxury all around the world due to a global shortage of semiconductors. If you're in the market for a new house or want to build a factory, prices are going through the roof and projects are getting delayed because building materials—particularly those sourced from overseas, which is the case for most countries—are scarce and will take longer to acquire,” reported GZERO Media’s Carlos Santamaria.

Why are supply chains under such stress?

The crisis has been described as a portrait of scarcity. You might think the world is producing very few goods. Some have even compared the situation to the Soviet Union’s chronic shortages, which reflected the failure of centralized planning.

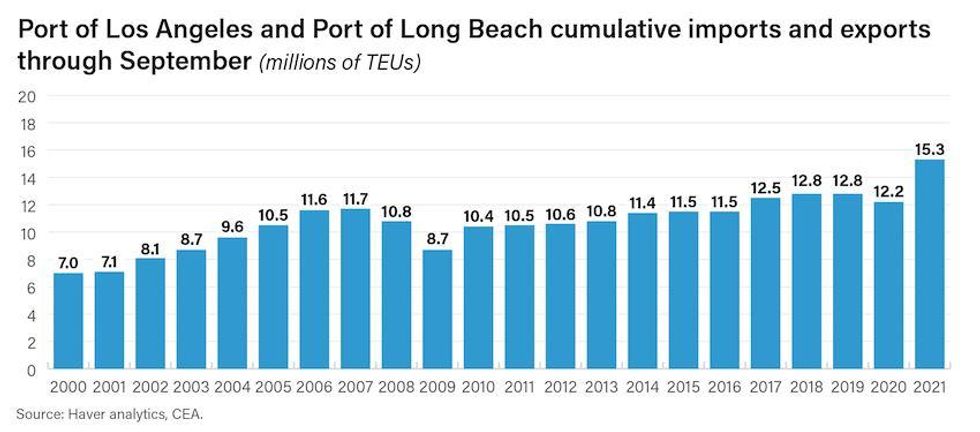

The truth is the opposite. More, not fewer, goods are being manufactured and shipped than normal. In fact, as the White House Council of Economic Advisers explained, this year “[US] ports are actually moving more containers in and out than in any year since 2000 (moving about 19 percent more than in either of the previous two pre-pandemic years of 2018 and 2019).”

That’s what’s straining the system.

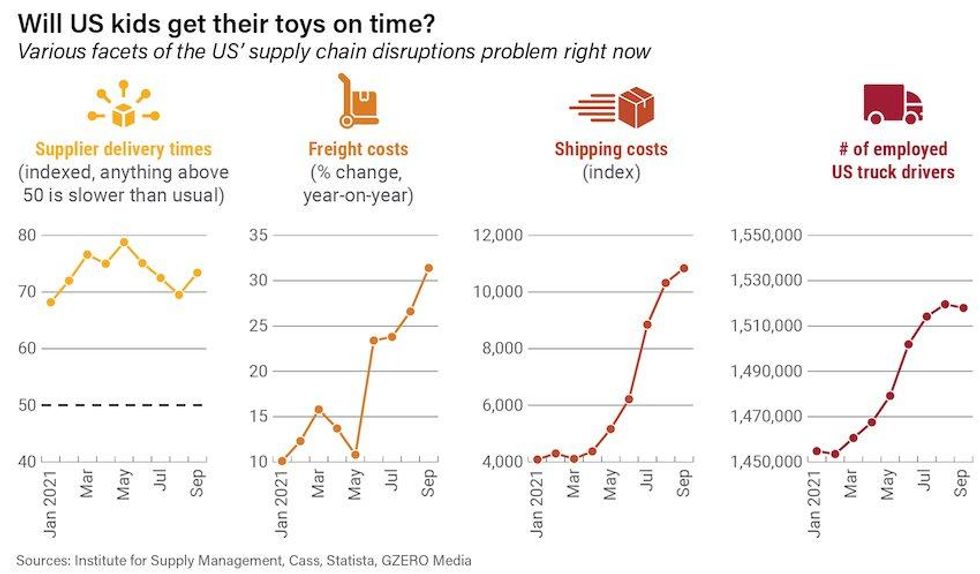

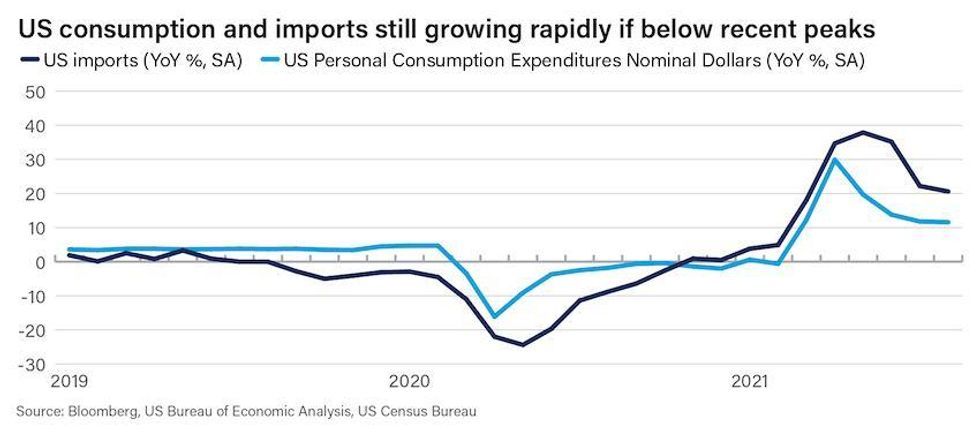

America’s massive fiscal response to the pandemic (totaling nearly $5 trillion) gave US consumers extra cash they couldn’t spend on in-person services like haircuts or travel, boosting demand for (mostly imported) goods. As Covid subsided and the economy reopened in the spring, appetite for stuff only grew further. At the same time, the pandemic forced many manufacturing and distribution operations (first at home but now predominantly in China, Vietnam and other export hubs with strict lockdowns) to temporarily shut down, reducing global goods output. Partly due to extensive labor shortages caused by the delta wave and a tightening job market, but also to preexisting fragilities in the “just-in-time” model, supply chains have been unable to keep up with the surge in demand.

The data bears this out.

“By several measures of the economy, we're seeing an absolute boom right now,” wrote Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal. Consumption and imports are way above pre-crisis trends. The latest manufacturing survey from the Dallas Fed shows “extremely robust, above-average measures for things like production, new orders, growth rates, and hiring,” Weisenthal reported, claiming that a key reason behind America’s supply chain woes is simply that “Americans have money to spend and they're spending a lot of it.”

Supply chains weren’t designed to withstand the rapid increase in output necessary to satisfy Americans’ unprecedented appetite for stuff. As Slate’s Jordan Weissmann wrote:

There are only so many berths where cargo ships can dock, and only so many cranes to unload them. There are only so many trucks that can enter and exit the port at a time, and only so many warehouses where goods can be stored. And there are also only so many trained dock workers or truck drivers available to actually do these jobs.

Instead of Soviet bread lines, think of what happened with Clorox wipes during the early pandemic days: there’s more demand than ever and production has increased fast, but not enough to meet the onslaught of new orders.

As Weissmann put it, it is a crisis of abundance, not scarcity.

When will the problems subside?

Not for a while. Policymakers including transportation secretary Pete Buttigieg, Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell, and World Trade Organization director-general Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala have said the supply chain issues could persist well into 2022. This means that they’ll still be around through the holiday season.

However, as the world enters the New Year, vaccination proceeds apace, and the global economy continues to re-open, demand for goods will go down to more normal levels and bottlenecks along the supply chain should ease.

According to a blog post published by the White House Council of Economic Advisers, the stresses on supply chains should be expected to diminish “as COVID fades and as people rebalance their spending more evenly between goods and services.”

But even if supply and demand both normalize soon, it may still take several months for supply chains to clear the existing backlog. Don’t expect guaranteed overnight deliveries to resume anytime soon.

What can policymakers do about it?

Over the last three weeks, President Biden has met with stakeholders from the shipping and logistics industry, along with executives from the country’s largest retailers, to ramp up efforts to tackle lingering port bottlenecks and container logjams.

On October 13, President Biden announced public and private commitments to ease cargo congestion and mitigate shipping delays, including enhanced data sharing and a deal to keep the Port of Los Angeles running 24/7 through Christmas.

It’s unclear how much these interventions will help or to what extent Biden can actually make the situation better, especially before consumer demand shifts back to pre-pandemic patterns and the import boom eases off. After all, record numbers of vessels have been stranded outside L.A.-area ports (which process 40% of all shipping containers arriving in the US) despite the latter already operating above full capacity, and many of the supply bottlenecks originate in Asia and other parts of the world where the US government has limited power to intervene. Outstanding shortages of shipping vessels, cargo containers, chassis, truck drivers, railway workers, and warehouse space can’t be addressed by executive fiat.In the medium term, infrastructure investments would help make supply chains more resilient. As transportation secretary Pete Buttigieg said to CNN:

This is one more example of why we need to pass the infrastructure bill. There are $17 billion in the President's infrastructure plan for ports alone and we need to deal with these long-term issues that have made us vulnerable to these kinds of bottlenecks when there are demand fluctuations, shocks and disruptions like the ones that have been caused by the pandemic.

Unfortunately, in the short run there is little the government can do beyond ordering round-the-clock port operations and urging corporates to do their part in a national struggle—measures insufficient to address today’s supply chain disruptions.

How will this crisis affect Biden politically?

Supply chain logjams and their consequences—delivery delays, shortages, and inflation—are undermining the “America is back” case the Biden administration hoped to make in the wake of Covid-19. Some in the right-wing media are accusing him of “stealing Christmas,” a message that is likely to resonate with voters if the problems persist into the holiday season.

It doesn’t matter that the disruptions are a symptom of a booming economy, credit to Biden’s successful fiscal policies. Politics is perception, and the president’s approval ratings have dropped 10 points since June, no doubt in part due to these issues. A Christmas nightmare scenario poses a real political challenge for the administration, even if the president is not responsible and has few levers to solve it.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.