Marietje Schaake has watched Silicon Valley for years, and she has noticed something troubling: The US technology industry and its largest companies have gradually displaced democratic governments as the most powerful forces in people’s lives. In her newly released book, “The Tech Coup: How to Save Democracy from Silicon Valley,” Schaake makes her case for how we got into this mess and how we can get ourselves out.

We spoke to Schaake, a former member of the European Parliament who serves as international policy director at the Stanford University Cyber Policy Center and international policy fellow at Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. She is also a host of the GZERO AI video series. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

GZERO: How do private companies govern our lives in ways that governments used to — and still should?

Schaake: Tech companies decide on civil liberties and government decision-making in health care and border controls. There are a growing number of key decisions made by private companies that used to be made by public institutions with a democratic mandate and independent oversight. For-profit incentives do not align with those.

When tech companies curate our information environments for maximum engagement or ad sales, different principles take priority compared to when trust and verification of claims made about health or elections take precedence. Similarly, cybersecurity companies have enormous discretion in sharing which attacks they observe and prevent on their networks. Transparency in the public interest may mean communicating about incidents sooner and less favorably to the companies involved.

In both cases, governance decisions are made outside of the mandate and accountability of democratic institutions, while the impact on the public interest is significant.

Why do you present this not merely as a new group of powerful companies that have become increasingly important in our lives, but, as you write, as an “erosion of democracy”?

The more power in corporate hands that is not subject to the needed countervailing powers, the fewer insights and agency governments have to govern the digital layer of our lives in the public interest.

Why do you think technology companies have largely gone unregulated for decades?

Democrats and Republicans have consistently chosen a hands-off approach to regulating tech companies, as they believed that would lead to the best outcomes. We now see how naively idealistic and narrowly economically driven that approach was.

Silicon Valley is constantly lobbying against regulation, often saying that rules and bureaucracy would hold industry back and prevent crucial innovation. Is there any truth to that, or is it all talk?

Regulation is a process that can have endless different outcomes, so without context, it is an empty but very powerful phrase. We know plenty of examples where regulation has sparked innovation — think of electric cars as a result of sustainability goals. On the other hand, innovation is simply not the only consideration for lawmakers. There are other values in society that are equally important, such as the protection of fundamental rights or of national security. That means innovation may have to suffer a little bit in the interest of the common good.

What’s Europe’s relationship like with Silicon Valley at this moment after a series of first-mover tech regulations?

Many tech companies are reluctantly complying, after exhausting their lobbying efforts against the latest regulations with unprecedented budgets.

In both the run-up to the General Data Protection Regulation and the AI Act, tech companies lobbied against the laws but ultimately complied or will do so in the future.

What’s different about this moment in AI where, despite Europe’s quick movement to pass the AI Act, there are still few rules around the globe for artificial intelligence companies? Does it feel different than conversations around other powerful technologies you discuss in the book, such as social media and cryptocurrency?

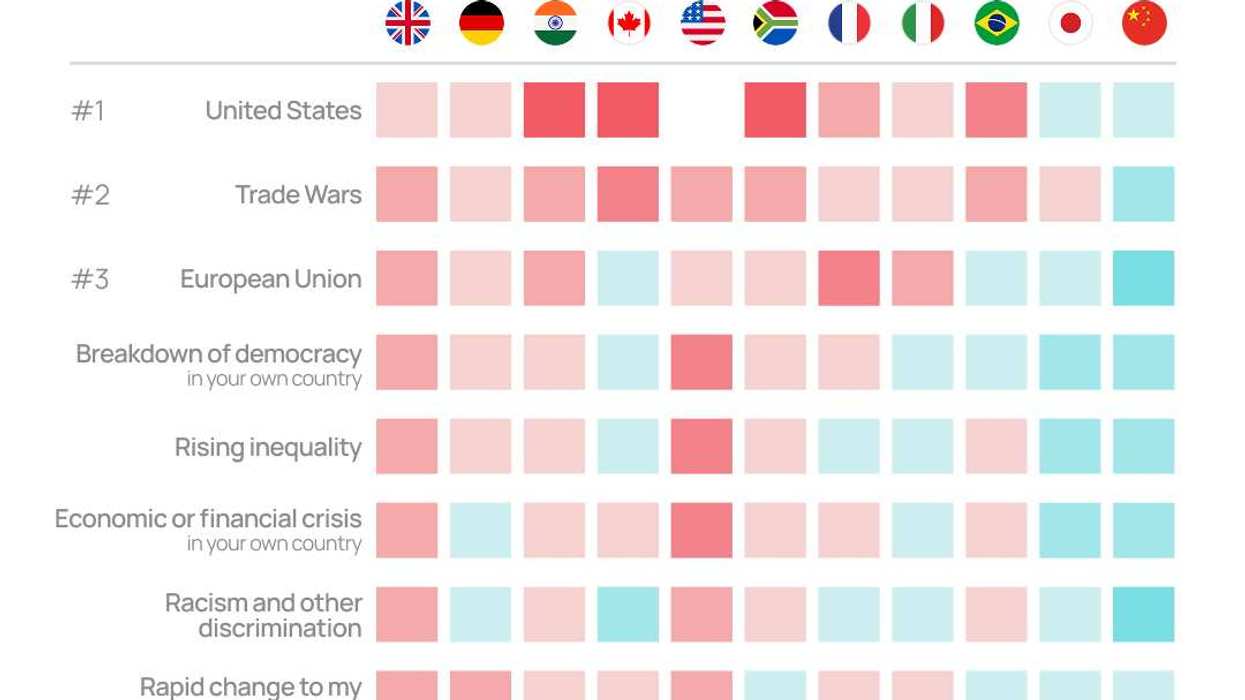

I have never seen governments step up as quickly and around the world, as I have in relation to AI, and in particular the risks. Part of that may be a backlash of the late regulation of social media companies, but it is significant and incomparable to any waves of other technological breakthroughs. The challenge will be for the democratic countries to work together rather than to magnify the differences between them.

You were at the UN General Assembly in New York last week, where there was a new Pact for the Future and HLAB-AI report addressing artificial intelligence governance at the international level. Does the international community seem to understand the urgency of getting AI regulation and governance right?

The sense of urgency is great, but the sense of direction is not clear. Moreover, the EU and the US really do not want to see any global governance of AI even if that is where the UN adds most value. The EU and US prefer maximum discretion and presumably worry they would have to compromise when cooperating with partners around the world. The US has continued its typical hands-off approach to tech governance in relation to AI as well.

There is also a great need to ensure the specific needs of communities in the Global South are met. So a global effort to work together to govern AI is certainly needed.

Back to the book! What can readers expect when they pick up a copy of ”The Tech Coup?”

Readers will look at the role of tech companies through the lens of power and understand the harms to democracy if governance is not innovated and improved. They will hopefully feel the sense of urgency to address the power grab by tech companies and feel hopeful that there are solutions to rebalance the relationship between public and private interests.

Can we actually save democracy from Silicon Valley — or is it too late?

The irony is that because so little has been done to regulate tech companies, there are a series of common-sense steps that can be taken right away to ensure governments are as accountable when they use technology for governance tasks, and that outsourcing cannot be an undermining of accountability. They can also use a combination of regulatory, procurement, and investment steps to ensure tech companies are more transparent, act in the public interest, and are ultimately accountable. This applies to anything from digital infrastructure to its security, from election technologies to AI tools.

We need to treat tech the way we treat medicine: as something that can be of great value as long as it is used deliberately.