In this special edition of Signal, we'll look at how to transform the Great Resignation into the Great Return. We track the future of work and workplace culture, a cautionary tale from Germany, and the 1.1 million women in the US whom employers need to woo back into the workforce. This edition is part of the “Living Beyond Borders” series, presented by GZERO and Citi Private Bank.

Thank you for reading — please tell your friends to subscribe here.

- The Signal team

Getting from the Great Resignation to the Great Return

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos SantamariaIt’s a job seeker’s market.

Over 47 million Americans voluntarily left their jobs last year, almost 13% more than in 2019. That was before the pandemic, which has upended the relationship between workers and employers as much as it has disrupted all our lives.

It’s not just a US phenomenon. High turnover rates extend across comparable OECD economies. Nearly a quarter of Brits and a third of Australians plan on switching jobs in the next several months.

The picture is somewhat different in the developing world. Hundreds of millions of people who lost their jobs during the pandemic — mostly in the informal economy — still can't find work because COVID obliterated entire industries such as tourism. Chinese companies, meanwhile, are struggling to retain young employees who are fed up with low pay and long hours.

The Great Resignation is thus a global problem, in varying ways, as will be the Great Return. With the omicron scare easing in the West, many companies there have begun trying to figure out how to woo millions of now-remote (or recently resigned) employees back to the office — precisely at a time when it’s gotten harder to find and retain talent.

Here are three ways employers might have success.

The most obvious fix is to raise salaries. That’s already happening for some. US wages grew on average 4.5% last year, the highest annual rate in almost 40 years. But with US inflation currently at 7.5%, that annual bump is actually a pay cut in real terms, and higher salaries won’t entice everyone.

What’s more, upward pressure on salaries is likely to contribute to even higher inflation.

Another option is additional benefits for employees, especially those who feel more productive working from home and see little upside to returning to the office. Many companies have already adopted permanent hybrid schedules, with workers coming in twice a week.

But some CEOs want everyone in the office five days a week. They just don't get it, US organizational psychologist Adam Grant told GZERO World. Grant argues that worker productivity “is about the purpose and the process that you bring to your job (...) not about the place you happen to be doing it in.”

Apart from going hybrid, governments are increasingly backing experiments such as four-day workweeks to deliver more work-life balance. This approach has already been tested — with varying degrees of success — in Iceland, Spain, and it will soon be trialed in England.

Finally, companies that struggle to find talent where they’re based might opt to find it elsewhere, including overseas. That means more people working remotely from other US states or even abroad, which could have big political implications.

Imagine all those American manufacturing jobs that went to Mexico thanks to NAFTA, or to China after Beijing joined the WTO. This time, though, US labor outsourcing would hit the laptop class — the one that has benefited the most from globalization and a digital-first world.

As Eurasia Group CCO Alex Kazan points out on the Living Beyond Borders podcast, a post-pandemic hiring spree of remote labor from low-income countries could be politically toxic amid the surge of nationalism and protectionism we've seen in places around the world. But if done right, it could also be viewed as an expansion of a flexible gig economy that can spur greater inclusion in a global workforce.

“We're still a long way away from a global labor pool, but certainly the normalization and acceptance of technologies that enable remote work make that a more plausible future,” Kazan says.

Meanwhile, WFH is not going away. If companies in advanced economies want to lure their employees back to the office, most firms will need to reshape workplace culture to embrace remote working and hybrid models.

The Graphic Truth

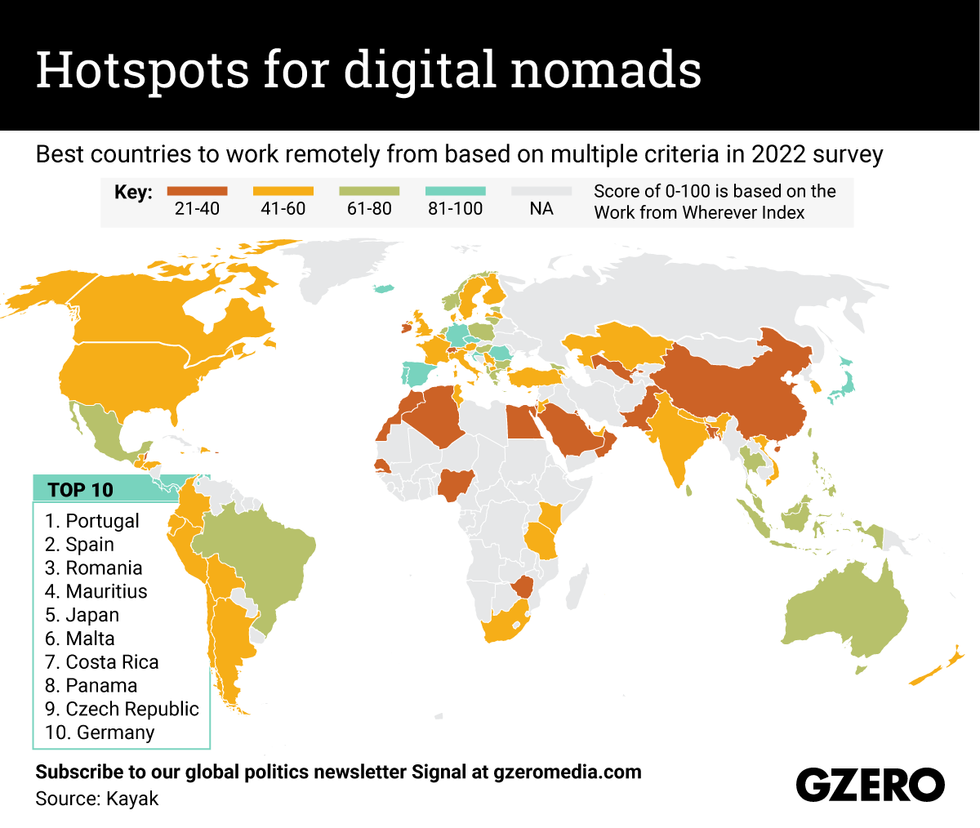

The pandemic has enabled some professionals to work remotely from home — or anywhere. Digital nomads wander the world in search of the perfect place to hunker down with their laptops, prompting some countries to offer them special visas. Where should you go if you can work from anywhere?

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Private Bank

Citi Private BankJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

What We're Watching: Gorillas in the gig economy & work struggles for the "sandwich generation"

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiGorilla unicorn to gig goat: a cautionary tale. Last year, a new Berlin-based food delivery company called Gorillas was going bananas. With its minimal branding, pro-biker vibes, and good service, the company became the first German tech “unicorn,” meaning it raised enough capital to be valued at more than a $1 billion dollars. But then the wheels came off as its gig workers, angry about late payments and poor working conditions, tried to organize in protest, and hundreds were fired. The company continues to function, but it recently set up its holding company in the Netherlands. The tale of Gorillas is both an inspiring and cautionary one. Over the past 10 years, gig work, facilitated by new technology platforms — think Uber, Seamless, Fiver, etc — has grown rapidly. Close to 30 million Europeans secure work through digital platforms, and the EU says that could rise to 43 million by 2025. In the US, one in 10 American adults relied primarily on “on demand” work as of 2020. This has vastly expanded opportunities for employment and broadened companies’ ability to source talent and skills on demand. But that flexibility comes at a cost for employees, who lack the workplace protections and benefits normally associated with full- or part-time work. Policymakers are still trying to balance the pros of flexibility with the cons of “precarity.” The EU is leading the legislative charge on this, with a sweeping set of reforms that would force gig platforms to classify their workers as employees and give them more bargaining rights. Supporters say it will boost the gig economy to a fairer footing, while critics worry it will make them less efficient and more expensive.

Is the “sandwich generation” being frozen out? The pandemic has been difficult for people of all demographics, but the costs – and disruptions – have been particularly severe for the “sandwich generation.” Those include people in their 30s, 40s, and early 50s who are trying to balance careers along with caregiving responsibilities for young children and parents. This burden is disproportionately felt by women, who make up 60% of this demographic in the US, according to Pew. Anecdotal evidence in the US, UK, and parts of the European Union, suggests that the pandemic has forced these already-stretched individuals to give up jobs and shed work hours in order to take on the added burden of helping with home-schooling and elder-care responsibilities. There are signs that many of these women have not made their way back into the labor force. While men have mostly recouped their pandemic job losses in the US, women are lagging far behind: there were at least 1 million fewer women in the workforce in January 2022 than two years earlier, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Some experts warn that things are still taxing for older members of the “sandwich generation” because young adults, whose education and work life have been disrupted for the past two years, are becoming more dependent on their parents for housing and other support. Many businesses are ramping up “return-to-work” programs to help lure women back to work after long absences. But these programs are often limited in scope, and being out of work for extended periods can make it more difficult to secure desirable roles.

Hard Numbers: India needs non-agri investment, American women lag behind, WFH forever, Iranian job woes

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle Debinski90: India will need to create 90 million new non-agricultural jobs by 2030 to reach its economic potential, according to McKinsey. The pandemic drove tens of millions out of cities to work in farming back in their villages, but economists now say that the government needs to boost urban production to maximize growth.

63: The US economy has shed millions of jobs since March 2020, with female workers accounting for 63% of the lost gigs, according to the National Women’s Law Center.

91: A whopping 91% of Iranians surveyed say they feel negative about their local job markets. The Iranian labor market continues to be strangled by tough economic sanctions, but if a nuclear deal is reached in the near term, employment opportunities and industry will expand significantly, experts say.

59: Two years into the pandemic, 59% of Americans who can work from home say they are doing so all or most of the time. Before the pandemic, 23% said they worked from home frequently.Podcast: Living Beyond Borders

GZERO Media and Citi Private Bank teamed up to produce a special-edition podcast series called “Living Beyond Borders.” The segments focus on everything from pandemic lessons and what to expect at work in 2022 to China’s changing trade priorities and the importance of biodiversity to the global economy.

Listen to the series here.

This edition of Signal was written by Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, and Carlos Santamaria. Edited by Tracy Moran. Graphic by Ari Winkleman, art by Annie Gugliotta.