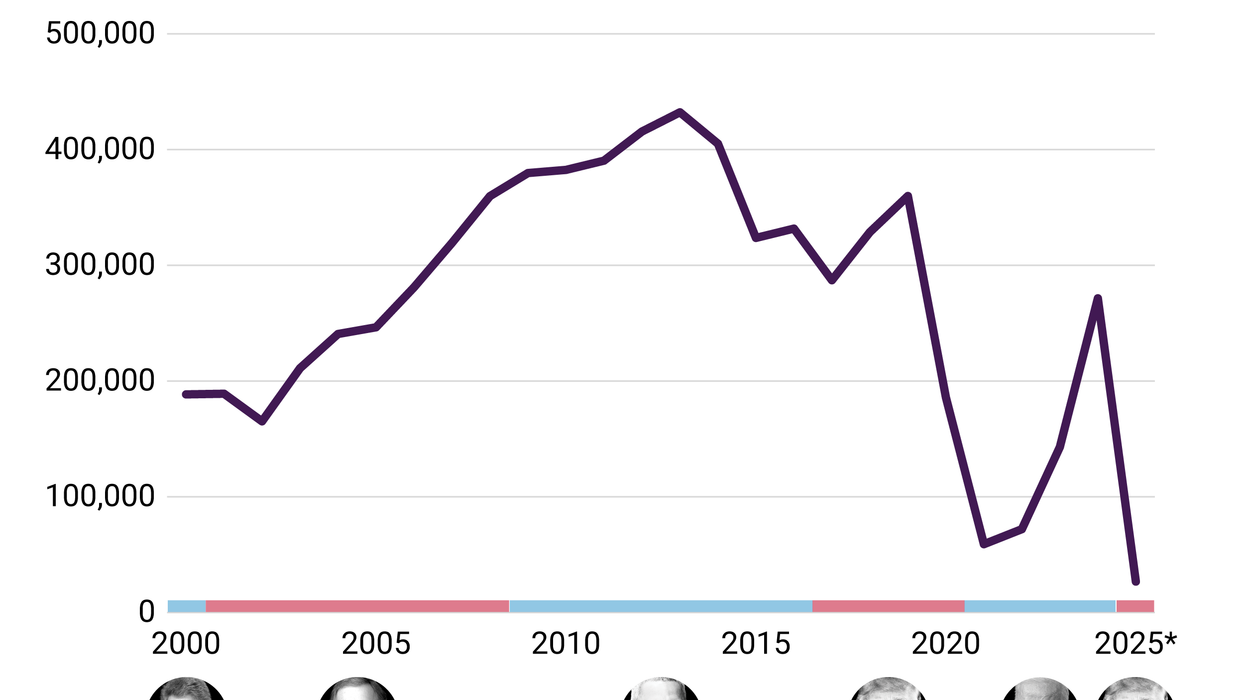

Seven warships, a nuclear submarine, over two thousand Marines, and several spy planes. Over the past week, the United States has stacked a serious military footprint off Venezuela’s coast. The White House claims this is a drug enforcement mission. And sure enough, yesterday the US Navy carried out its first – though surely not its last – lethal strike against a boat allegedly carrying drugs from Venezuela, killing 11 members of the Tren de Aragua gang.

But bringing amphibious assault ships and cruise missiles to a drug bust is like using a blowtorch to kill a mosquito: overkill. A deployment of this scale costs taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars, risks miscalculation and accidents, diverts scarce resources from more strategic theaters, and – fundamentally – it’s far more muscle than the stated mission requires.

Either this is history’s most expensive counter-narcotics operation or it’s … something more.

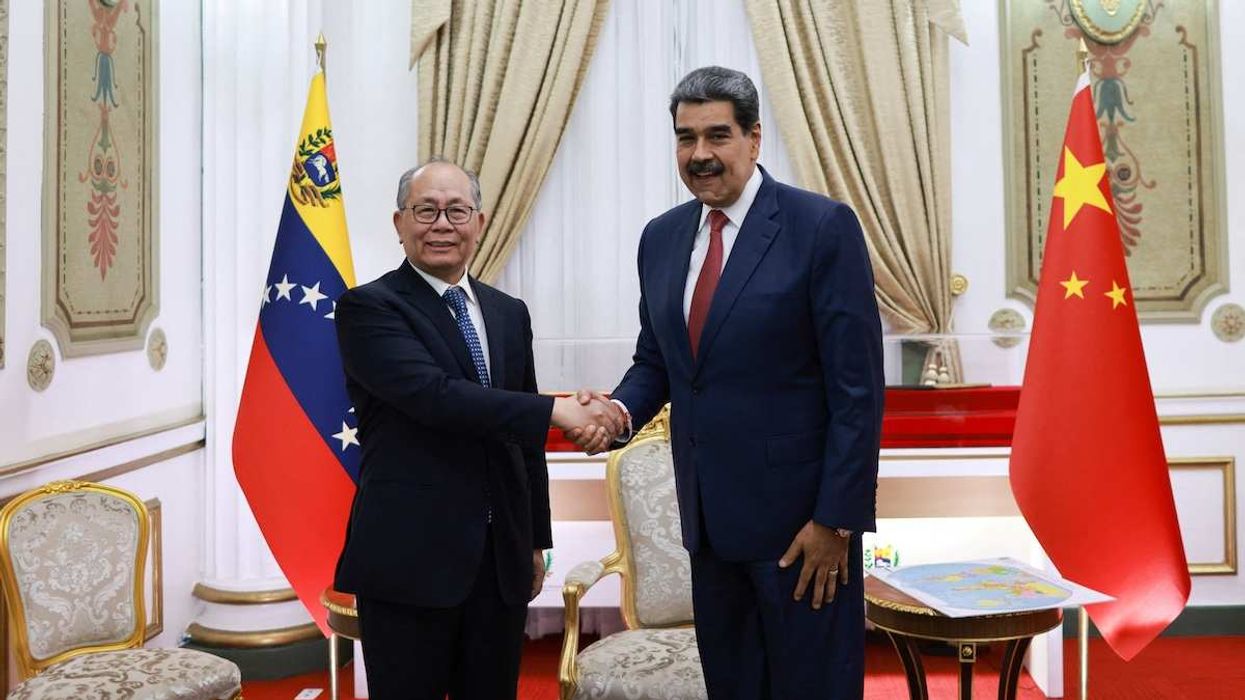

A run of legal and political escalations points to a bigger play. Over the last few weeks, the Trump administration designated Venezuelan cartels as terrorist organizations and Nicolás Maduro as their leader. It doubled the bounty on Maduro’s head to $50 million. It authorized the Defense Department to use force against cartels in Venezuela and Mexico. And it made a point of reiterating that the US does not recognize Maduro as a legitimate head of state protected by US law – a crucial step in creating legal cover to target him directly, if Trump so ordered. These moves happened before the flotilla started steaming south.

Add it all up and this reads like the opening act of a pressure campaign to unseat Maduro.

President Trump is usually – though not always (see Brazil, for example) – skeptical of regime change, but Secretary of State and national security adviser (and acting USAID Administrator, and acting Archivist) Marco Rubio has been pushing for a more active US intervention in Venezuela since his Senate days. For Rubio, whose worldview was shaped by Miami Cuban exile politics, hitting Caracas is about more than drugs, crime, and illegal migrants – it's about taking down what he sees as Cuba's oil-subsidized proxy and the first step in cleaning house across Latin America.

Trump himself has competing impulses. On one hand, he promised voters no new foreign wars and still mistrusts the Venezuelan opposition after getting burned by the Juan Guaidó fiasco in his first term. Unlike Rubio, he also has no principled commitments to the cause of Venezuelan democracy. Even as his administration tightened the screws on Maduro and his circle, it quietly reinstated Chevron’s license to pump Venezuelan oil earlier this year. The license is structured to keep oil moving but on terms that favor American interests rather than PDVSA, Venezuela’s state-owned oil monopoly.

On the other hand, Trump is not ideologically averse to all military action – only to politically costly quagmires – and he has plenty of reasons to want to see Maduro gone. Judging by the administration’s recent moves, Rubio may have succeeded in convincing the president that Venezuela offers the perfect opportunity for him to project strength on the global stage and take an easy victory lap at a time when the regime is brittle and some of his other big-ticket foreign policy gambits, such as Ukraine diplomacy, are flopping.

None of this implies boots on the ground. Trump has zero appetite for another Iraq that would be politically toxic and unpopular even with his MAGA base (not to mention that a ground invasion would require a much larger troop deployment).

But military actions against cartel infrastructure, key facilitators, or military assets propping up the regime? That would align with Rubio’s agenda, explain the scale of the buildup, and give Trump easier-to-sell wins that don’t risk messy entanglements. Most likely, the goal isn’t to seize territory or topple the regime in one go (though targeted decapitation strikes can’t be ruled out); it’s to ramp up the pressure on the people keeping Maduro in power, shifting their calculations and eventually threatening his standing.

That’s how most autocracies crack – from within. Venezuela's military has stuck with Maduro (and his predecessor, Hugo Chávez) through the country’s economic collapse and international isolation, but its loyalty is transactional. Fifty million-dollar bounties, a naval blockade, and the prospect of death by Tomahawk create powerful incentives to reconsider.

This isn’t to say the regime is about to collapse. Even if Maduro falls – still a big if – the military and palace power brokers would try to manage the transition and install his successor. Think Vice President Delcy Rodríguez or her brother, National Assembly President Jorge Rodriguez, both pragmatic insiders who've negotiated with Washington and the opposition before. The ruling PSUV has far-reaching institutional control; any deal that persuades regime elites to stand down will require extensive power‑sharing and amnesty guarantees. The path to real elections and opposition government would be long, messy, and probably violent.

But that's getting ahead of ourselves. The immediate question is simpler: are we looking at theater or prelude? My bet is it’s a little bit of both, but we will know soon enough. Those around Maduro must be wondering whether he’s still worth the risk of sticking around to find out.