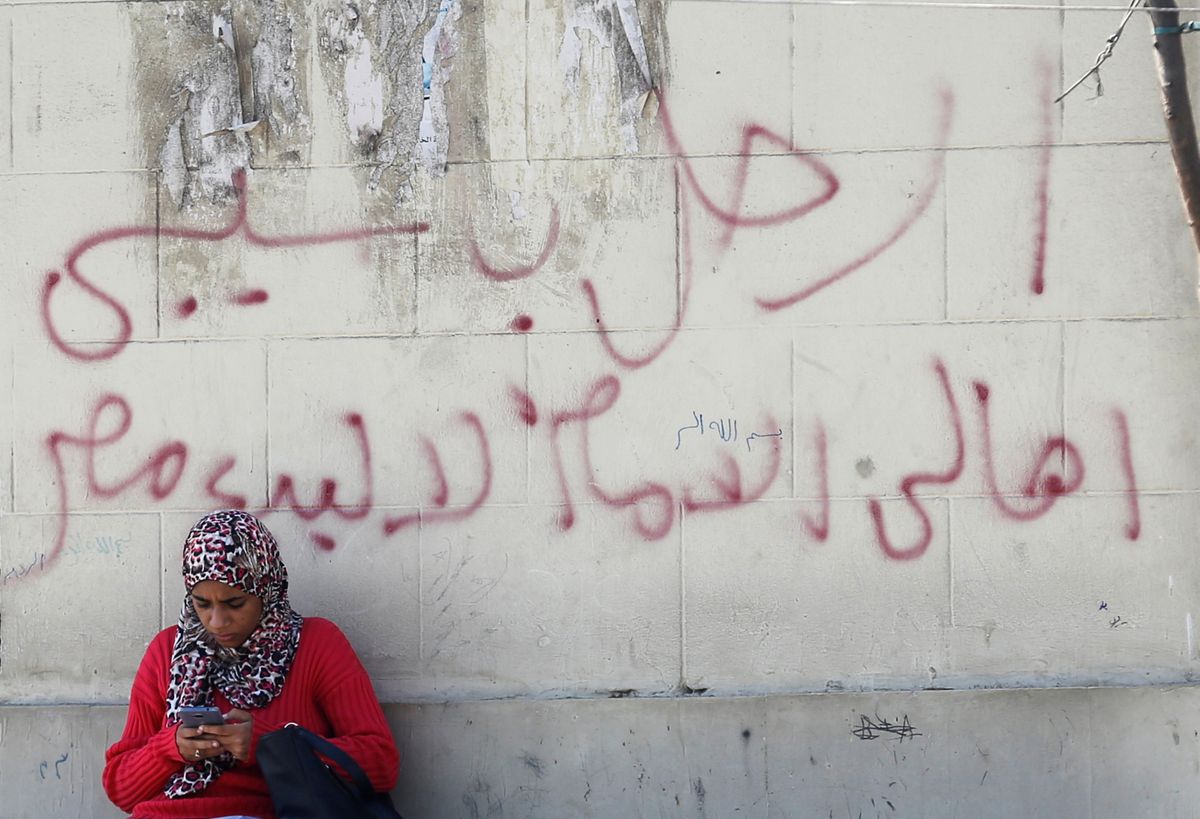

Are you Egyptian? Do you have a large internet following? Then you had better watch what you say. A law passed by the country’s parliament this week means that anyone with more than 5,000 social media followers will be treated like a media company under the country’s strict media laws, which make it a crime to engage in vaguely defined bad behavior, like inciting law-breaking or publishing false information. What the Egyptian government portrays as a strike against fake news, critics see a further muzzling of speech in a country that routinely jails journalists and scores near the bottom of global press freedom rankings.

But there’s a broader trend at work here: governments around the world are attempting to control the flow of subversive information (however they define it) through their societies.

Many countries, including Egypt, have adopted a technocratic approach to information control: by passing laws (and in China’s case, implementing sophisticated censorship systems) that regulate online speech, governments can not only clamp down on specific threats, they create a broader chilling effect that encourages self-censorship.Then there’s the blunt-force option: disconnecting the internet to stop rumors and protests from spreading. Shutoffs have serious downsides: for one, they’re expensive, since many people now depend on the internet for their livelihoods. But they are a popular tool across parts of Africa, where English speaking regions of Cameroon were cut off from internet for much of last year, as well as in India, where authorities have pulled the plug more than 170 times since 2012, most often in anticipation of public unrest in specific regions of the country.

Finally, there is Russia’s favored approach: undermine trust in information by pushing out so much disinformation that people don’t know what to believe. It’s a slow-burn strategy that’s been supercharged by the rise of social media and is now being weaponized and exported to the West. So far, the US and UK have resisted passing new laws aimed at stamping out fake news, but Germany, which has a history of censoring hate speech, has adopted the technocratic approach. Last year, it passed a law that threatens websites that fail to quickly delete material that contains incitements to hatred or crime, slander, or other verboten content or face stiff fines. If fake news rocks the 2018 US midterms, more democracies may decide they have no choice but to follow Germany’s lead.