A political outcry over migrant children separated from their families at the United States’ southern border. Germany’s coalition government on the brink of collapse. Italy squabbling with its neighbors over who should accept boatloads of asylum seekers. The searing politics of immigration policy are all over the news again in recent days.

And yet around the world, increasingly anti-immigrant governments are taking differing approaches to coping with unwanted arrivals — each has its political upsides and pitfalls.

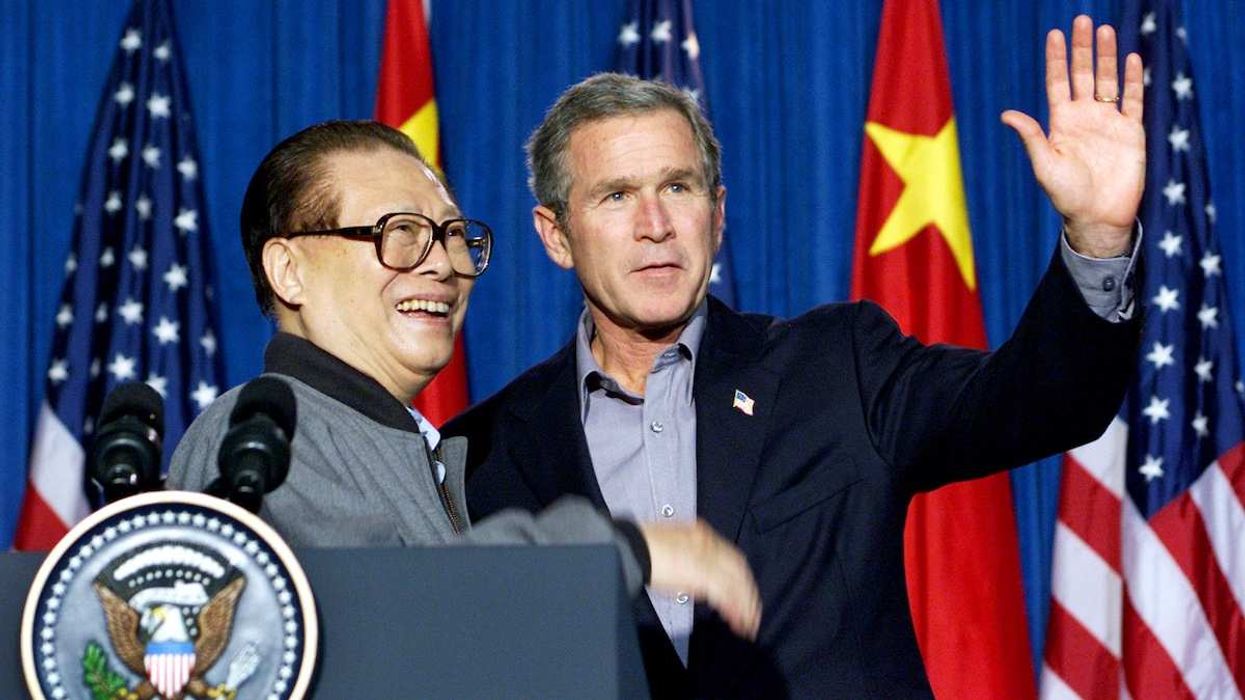

The US approach is based on deterrence: The Trump administration believes that a get-tough policy on prosecutions at the border — the grounds for the recent separation of migrant children from their families — will discourage other migrants from attempting to enter the country illegally. Time will tell if it has worked, but the downside is a moral backlash at home against an inhumane policy and a loss of (already tenuous) credibility in making human rights claims against other countries abroad. Trump, for his part, seems unconcerned about either — his administration has doubled down, and a majority of GOP voters support him.

Meanwhile in Europe — where the idea of setting up camps for people brings dark echoes of the not-so-distant past — governments are looking to outsource the problem. In the face of a growing anti-immigrant backlash in some countries, EU leaders are considering a proposal to house migrants in special “hubs” outside of Europe, where their asylum claims would be processed. The proposal emulates earlier deals between the EU and Turkey, and Italy and Libya, aimed at corralling migrants before they reach EU borders. The upside for European governments is that migration becomes someone else’s problem. The downside is being at the mercy of the goodwill (as in Turkey) or political fragility (as in Libya) of their outsourcing partners.

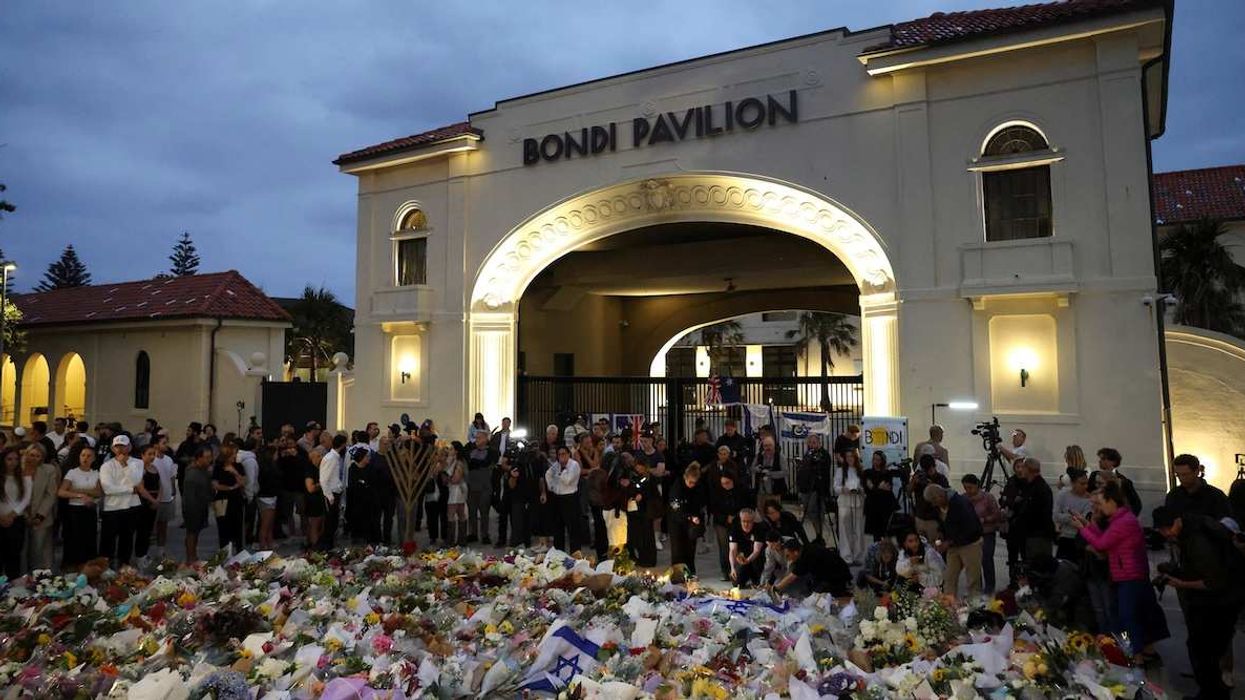

On the other side of the world, Australia combines the two approaches. A zero-tolerance migrant policy diverts so-called “boat people” — largely refugees from Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan — to internment camps in other countries: one on the tiny island nation of Nauru nearly 2,000 miles from Aussie shores and, until its recent closure, another on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea. The grim outposts are a deterrent of their own, but they are out of sight, out of mind for Australian voters. In ruthless political terms, Australia’s strategy — which the UN High Commissioner for Refugees last year called contrary to “common decency” — has worked. Boat arrivals have plunged after Australia began its offshoring policy and aggressively turning back migrant voyagers. As in the cases above, apart from the sheer human cost, the political downside is lost moral authority.