News

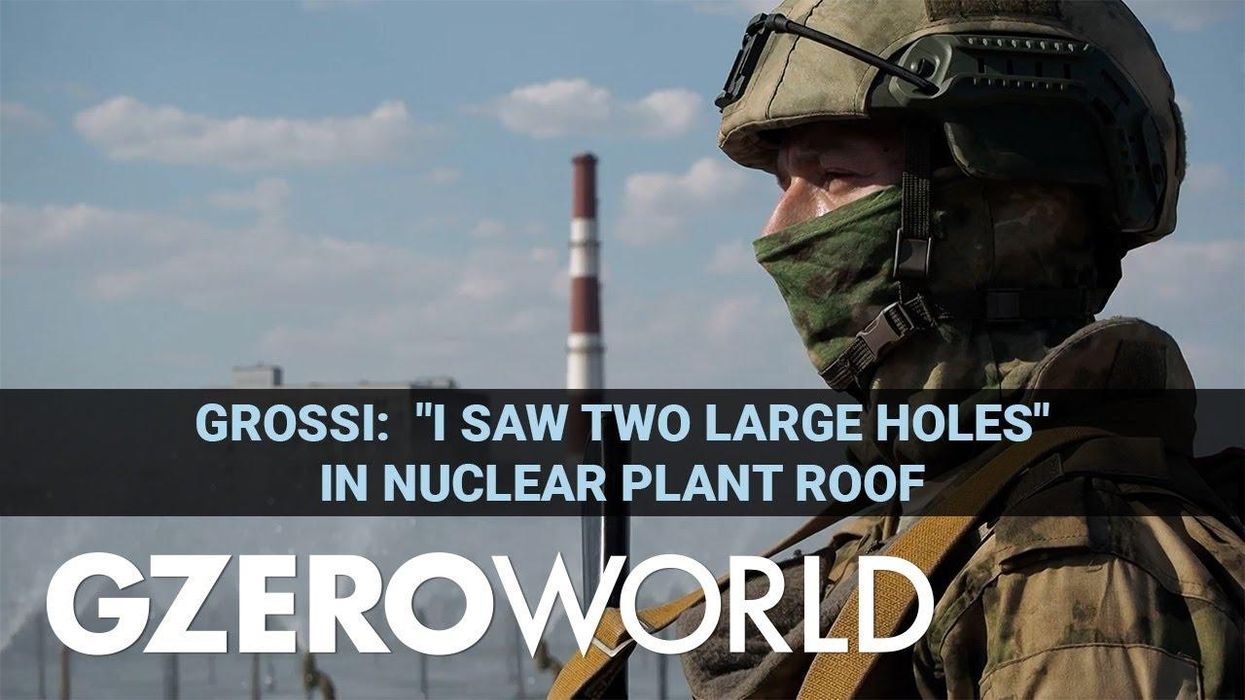

Is the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant at risk of attack?

Kyiv has warned of an impending Russian attack on the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in southeast Ukraine, raising fresh fears of a nuclear disaster in a region all too familiar with the risks of nuclear calamity (Zaporizhzhia is just 325 miles south of Chernobyl).

Jul 05, 2023