VIDEOSGZERO World with Ian BremmerQuick TakePUPPET REGIMEIan ExplainsGZERO ReportsAsk IanGlobal Stage

Site Navigation

Search

Human content,

AI powered search.

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

GZERO World Clips

Highlights from the GZERO World with Ian Bremmer weekly television show.

Presented by

Are The US and China on Collision Course in The South China Sea? Senator Chris Coons talks about China's ambitions for a blue water navy and what it means for US security.

More from GZERO World Clips

Join us live on Jan. 5 for the Top Risks of 2026 with Ian Bremmer

December 16, 2025

Tools and Weapons – In Conversation with Ed Policy

December 16, 2025

Six elections to watch in 2026

December 16, 2025

ask ian

Dec 16, 2025

Puppet Regime

Dec 16, 2025

Wikipedia's cofounder says the site crossed a line on Gaza

December 16, 2025

Quick Take

Dec 15, 2025

An ally under suspicion

December 15, 2025

GZERO World with Ian Bremmer

Dec 15, 2025

Economic Trends Shaping 2026: Trade, AI, Small Business

December 13, 2025

Why we still trust Wikipedia, with cofounder Jimmy Wales

December 13, 2025

Understanding AI in 2025 with Global Stage

December 13, 2025

Ian Explains

Dec 12, 2025

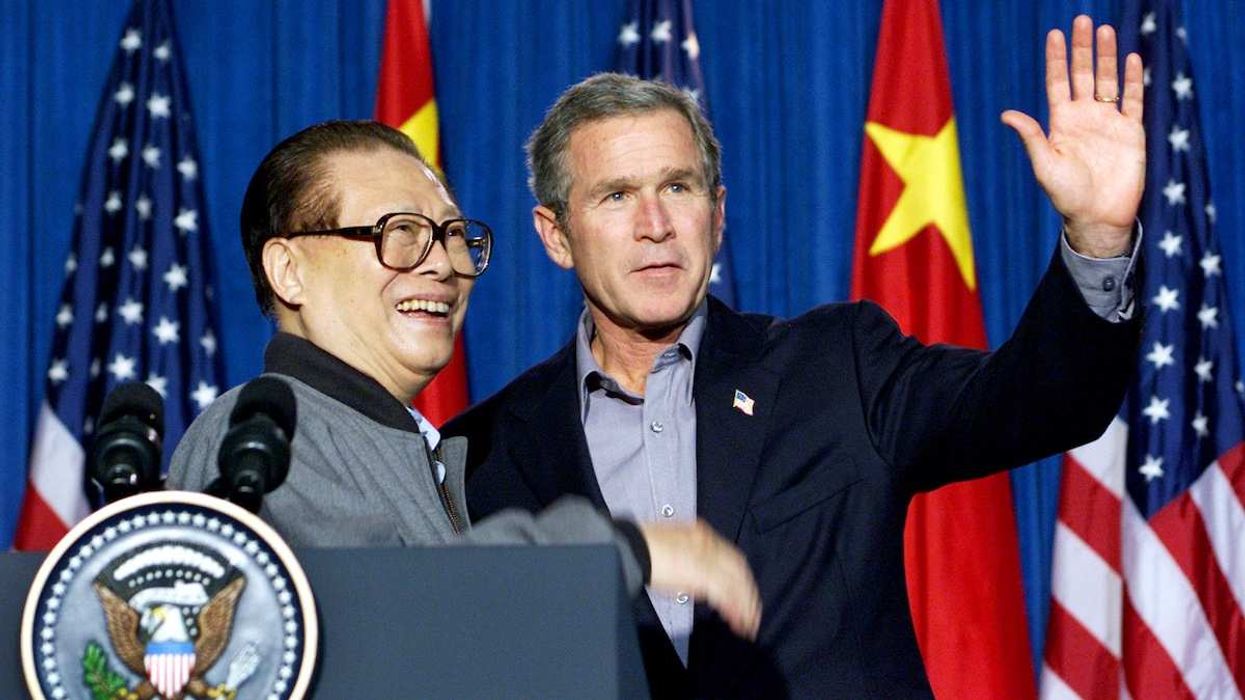

How chads and China shaped our world

December 12, 2025

You vs. the News: A Weekly News Quiz - December 12, 2025

December 12, 2025

Republicans lose on Trump’s home turf again

December 11, 2025

It’s official: Trump wants a weaker European Union

December 10, 2025

The power of sports

December 10, 2025

Japan’s leader has had a tricky start. But the public loves her.

December 10, 2025

What’s Good Wednesdays™, December 10, 2025

December 10, 2025

Walmart's $350 billion commitment to American jobs

December 10, 2025

Tools and Weapons – In Conversation with Ed Policy

December 09, 2025

Honduras awaits election results, but will they be believed?

December 09, 2025

Geoffrey Hinton on how humanity can survive AI

December 09, 2025

Notre Dame, politics, and playing by their own rules

December 08, 2025

Trump’s new national security strategy targets Europe

December 08, 2025

Egypt’s Undemocratic Election - And Why the West doesn’t care

December 08, 2025

'Godfather of AI' warns of existential risks

December 08, 2025

Anatomy of a Scam

December 06, 2025

The human cost of AI, with Geoffrey Hinton

December 06, 2025

Will AI replace human workers?

December 05, 2025

The genocide no one talks about any more

December 05, 2025

Freelance Producer- Broadcast and Digital Video

December 05, 2025

You vs. the News: A Weekly News Quiz - December 5, 2025

December 05, 2025

Why won’t the right unite in Western Europe?

December 04, 2025

The Ukraine peace push is failing. Here's why.

December 03, 2025

The AI economy takes shape

December 03, 2025

Then & Now: Can Haiti's government hold an election?

December 03, 2025

What’s Good Wednesdays™, December 3, 2025

December 03, 2025

Walmart's $350 billion commitment to American jobs

December 03, 2025

Trump, Russia, and a deal Ukraine can’t accept

December 02, 2025

What’s next for Zelensky?

December 02, 2025

Trump threatens regime change in Venezuela

December 02, 2025

Tools and Weapons – In Conversation with Ed Policy

December 01, 2025

The kids are not alright

December 01, 2025

Crisis en Venezuela: Trump, Maduro, Xi, y Putin CANTAN!!!

November 29, 2025

Turkeys reject Trump's pardon

November 26, 2025

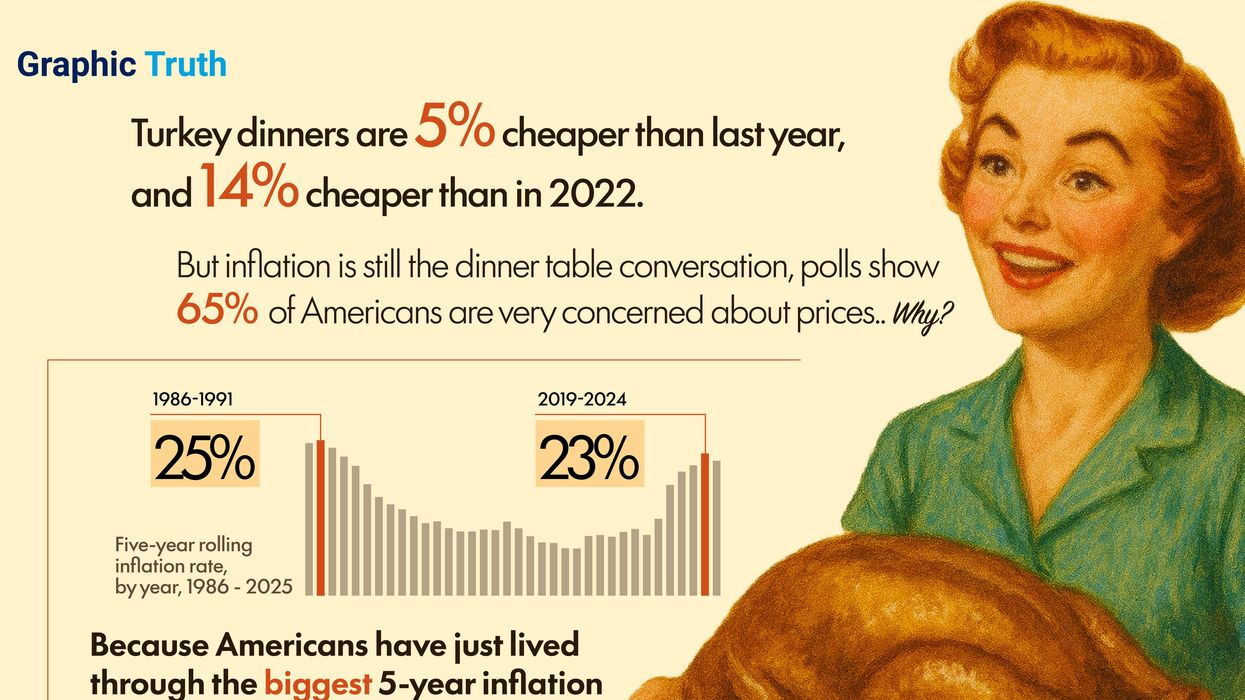

Graphic Truth: Turkey is cheaper, but inflation still gobbles

November 26, 2025

Five stories to be thankful for

November 26, 2025

Bolsonaro reacts as Trump scraps Brazil tariffs

November 25, 2025

Pakistan slides deeper into autocracy

November 25, 2025

Is Trump’s trade strategy backfiring abroad?

November 25, 2025

Toppling Maduro would be "the easy part" says former Ambassador

November 25, 2025

Tools and Weapons – In Conversation with Ed Policy

November 24, 2025

Europe divided as US pushes Ukraine-Russia peace deal

November 24, 2025

Japan-China spat over Taiwan escalates

November 24, 2025

Anatomy of a Scam

November 24, 2025

Could the US really invade Venezuela?

November 24, 2025

Gaming out a US-Venezuela war with ambassador James Story

November 22, 2025

Trump, Zelensky, and Putin discuss Ukraine peace deal

November 21, 2025

GZERO Series

GZERO Daily: our free newsletter about global politics

Keep up with what’s going on around the world - and why it matters.