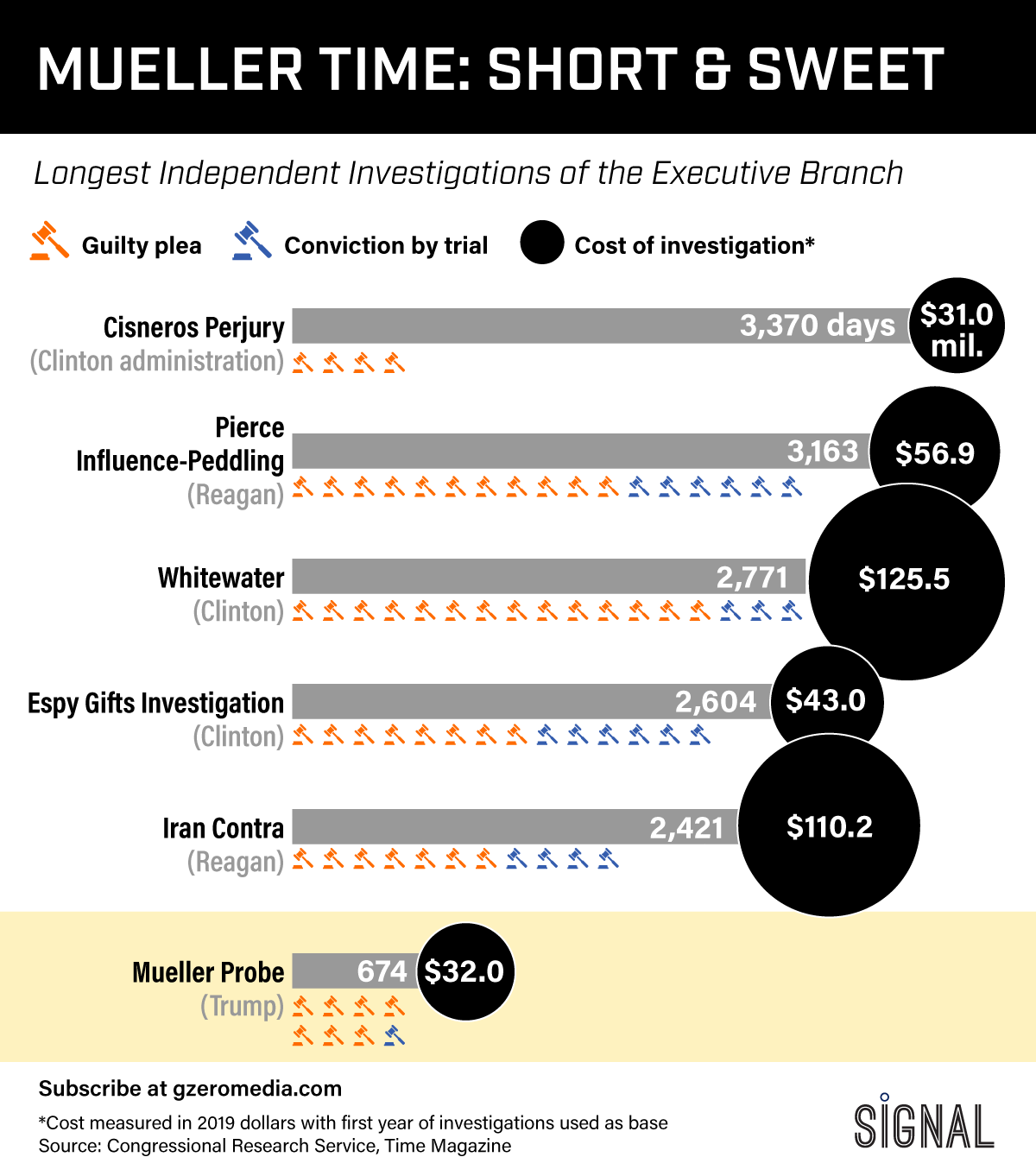

The Mueller investigation ran for 674 days at a cost of $32 million before it concluded in March. Here's a look at how that compares to other, similar investigations over the years.

News

Graphic Truth: The Mueller Investigation in Context

By Kevin Allison,

Kevin Allison

Kevin Allison is a Senior Editor for Signal. Based in Washington DC, he looks at how technology is reshaping global affairs. Kevin is also a Director in the Geo-Technology practice at Eurasia Group. Kevin holds degrees from the University of Missouri and from Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. He was also a Fulbright Scholar in Vienna, Austria and a 2015 Miller Journalism Fellow at the Santa Fe Institute. Prior to GZERO Media and Eurasia Group, Kevin was a journalist at Reuters and the Financial Times. He has lived in eight US states and has been an expat four times.

Gabriella Turrisi