German engineer Carl Benz designed the world’s first vehicle with an internal combustion engine back in 1885. Since then, we’ve gotten better at making cars, but the vast majority of the 1.4 billion vehicles on the road use engines based on the technology pioneered by Benz a century and a half ago.

Maybe not for long. As countries push for electric vehicles and begin to wind down the production and sale of ICE automobiles, the auto industry is changing, and so is the infrastructure that supports it. Is North America up to changing gears?

Last week, US Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, Canadian Minister of Transport Omar Alghabra, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, and Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan announced a Binational Electric Vehicle Corridor.

Dubbed the first of its kind – it’s not; the West Coast Green Highway connecting British Columbia and California has been around for years – the new corridor is part of a US-Canada push to set shared EV charging standards and further connect the neighbors and major trading partners. The new binational corridor will add substantial electric charging capacity between the two countries, building on the growth already seen in recent years. As part of the U.S. Alternative Fuels Corridors, a series of highways and roads covering 75,000 miles of the country, the latest US-Canada corridor will run nearly 900 miles/1,400 kilometers from Quebec City, Quebec, to Kalamazoo, Michigan, with 215 chargers spaced every 50 miles/80 kilometers. The route makes stops in Montreal, Toronto, and Detroit via one of the continent’s busiest trade routes.

Life is an Electric Highway … in some places

The US Department of Transportation has mapped both ready and pending corridors, which crisscross most states and are growing rapidly. Italian energy company Enel is investing in fast chargers, with plans to nearly double the number of stations along American highways. The Joint Office of Energy and Transportation estimates it will spend US$885 million in EV charging infrastructure across states for 2023 under the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program. The 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law includes funding aimed at building up to 500,000 public chargers – backed by US$7.5 billion in federal funds.

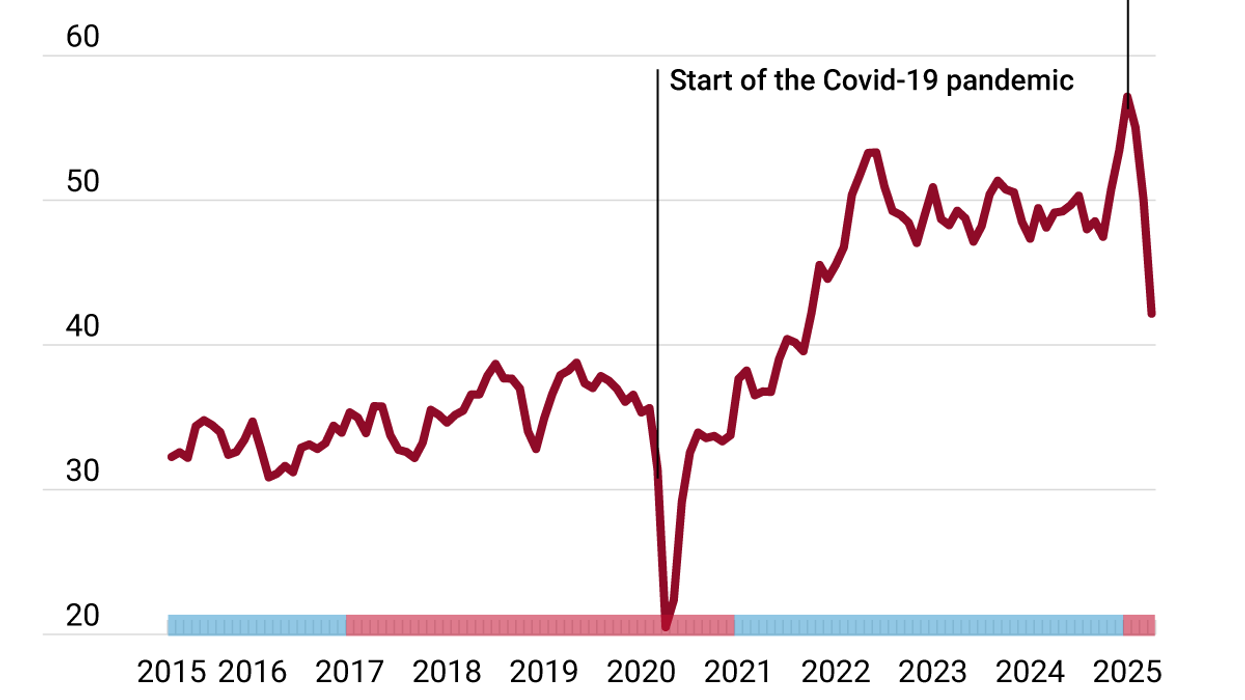

In March 2023, Canada hit the 20,000 charger milestone, growing 30% since last year. Gas giant and Suncor-owned Petro Canada is building “Canada’s electric highway,” a series of EV charging stations running from the country’s east coast in Halifax, Nova Scotia, to the west coast in Victoria, British Columbia. The company currently has at least one charger every 155 miles/250 kilometers along the route, while rival Shell Canada is planning its own major EV charging expansion across much of the country, aiming for more than 500 units by 2025. Both are supported by federal funds.

But is that enough to boost consumer confidence in EVs? Daniel Breton, president and CEO of Electric Mobility Canada, says EV charging capacity varies and is uneven. “It depends on where you are in Canada,” he says. “If you are in Quebec or B.C., the pace of deployment of public chargers is going at a fast pace.” The bigger question in those areas, he says, is whether car manufacturers can keep up with consumer demand, not charging station availability. But the same can’t be said of the prairie provinces, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. In other words, highway charging is improving, but rural and remote areas are proceeding unevenly.

The same problem plagues U.S. charging infrastructure. Michigan is trying to build capacity beyond common routes. Jeff Cranson of the Michigan Department of Transportation says the state is “in the process of selecting the most cost-effective contractors for installing EV charging stations” and that it aims to get that done with money to spare from its allotment of federal electric vehicle infrastructure funds “so that some of the $110 million in federal funding can be allocated around the state to support EV charging capacity in communities.” No doubt the future of EVs in Michigan relies not only on reliable charging along main corridors, but also in local communities.

ICE vehicles melting?

New EV infrastructure is both responding to and driving the decline of ICE vehicles, which is also getting plenty of help from government mandates. The US Environmental Protection Agency released new emissions standards aimed at boosting EV production, projecting that “EVs could account for 67% of new light-duty vehicle sales and 46% of new medium-duty vehicle sales in MY 2032.” That’s a far cry higher than today’s 7%. The Biden administration is pushing for half of all new vehicles sold to be EVs by 2030.

Some states are doing their own work to eliminate ICE vehicles, with California leading the way, as it has in the past on emissions standards. Last November, the state set its Advanced Clean Cars II regulations, which the California Air Resources Board says “will rapidly scale down emissions of light-duty passenger cars, pickup trucks and SUVs starting with the 2026 model year through 2035.” By then, the program will require all passenger vehicles sold in the state to be zero-emissions.

The Canadian federal government, meanwhile, plans to end the sale of new ICE passenger vehicles by 2035. With an interim goal of 60% EV sales by 2030, the country registered a national EV market share of 9.6% in Q4 2022. That’s up from 5.3% in 2021.

By comparison, Norway is a world leader, with 80% of new vehicles sold there being EV. It has a goal of 100% zero-emissions sales by 2025.

Will the binational EV corridor build consumer confidence?

The Quebec-Michigan EV corridor will offer integrated U.S.-Canadian infrastructure, with regularly spaced and reliable charging stations along the new route. They’ll include Direct Current fast chargers using Combined Charging System ports, a common type of port. Even Teslas, which feature a proprietary system and their own Supercharger network, can use CCS charging stations with an adapter.

It’s not like there aren’t any chargers along these roads now, but this big project is meant to help build EV capacity – and use. “It has to do with consumer confidence,” Breton says. “Right now, if you have an electric car, you really don’t have much of an issue to be able to travel across Canada or the U.S. on the highways.”

While it’s great that the countries are adding more chargers to heavily traveled areas, it’s essential, he says, that they “show Canadians and Americans that we can travel both sides of the border without having any issues.”