Almost lost in the flurry of outrageous things Donald Trump has said at campaign events recently were his comments on the future of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization at a rally in Las Vegas last Saturday.

The former president said he does not believe America’s NATO allies would be there to help defend the United States if it came under attack – as they are obliged to do under the alliance’s Article 5. The US is “paying for NATO, and we don’t get much out of it,” he said, glossing over the fact that the only time Article 5 has ever been invoked was after 9/11.

Comments like these have sparked speculation that Trump – should he win in November – might try to withdraw the US from NATO. This would serve as a seismic blow to global security, leaving new geopolitical fault lines, weakening democracies, and strengthening autocracies.

Trump’s first rodeo

Even if Trump is reelected, we have seen this movie before: In 2018, during his first term, he stormed into a NATO leaders meeting in Brussels like a tornado in a glass house, calling his allies “delinquents” for underspending on their defense.

At a time when few NATO partners were spending 2% of GDP on defense – the NATO guideline – Trump demanded 4% and implied he would bring US troops home if the allies didn’t comply. After a chaotic 24 hours and a series of hastily cobbled-together spending pledges, he left Brussels saying the US commitment to NATO “remains very strong,” claiming sole responsibility for allied spending pledges. It was a classic example of what The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg called the Trump Doctrine on foreign policy, where there are “No Friends, No Enemies” and “Permanent destabilization creates American advantage.”

If Trump again occupies the White House, his first NATO meeting could be a Brussels redux, but there are also signs that this time he means what he once reportedly told European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen: “NATO is dead, and we will leave ...”

What would NATO withdrawal mean?

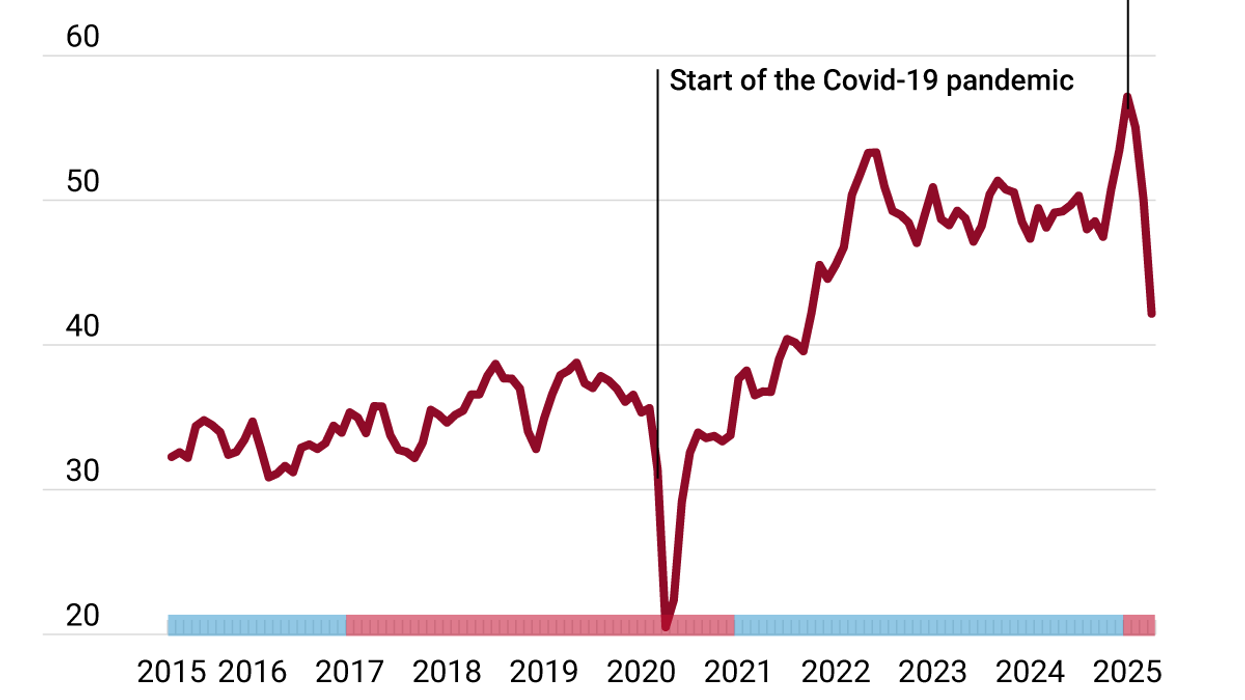

The US departing from NATO would not necessarily kill the alliance, but Washington’s contribution is irreplaceable: NATO estimates suggest the US spent $743 billion on defense last year, compared to $356 billion for the rest of the alliance put together. That was the equivalent of 3.49% of America’s GDP, with only Poland spending more proportionally. Nineteen of 30 NATO member states spent less than 2%.

But the Europeans are already preparing for the prospect of a Trump victory. Defense expenditure rose 8.3% last year by members, excluding the US, and European politicians are calling for countries on the Continent to build their own nuclear umbrella. France and the United Kingdom have hundreds of warheads, but there has been a noticeable reluctance from other allies like Germany to hand over the responsibility for their defense to Paris or London.

The Europeans at least have political institutions that they can coalesce around.

Even if Trump doesn’t withdraw, the bloc’s deterrence is dependent on political unity – unity which has proven vital to Ukraine’s defense in its fight against Russia. After everything Trump has said publicly, who in Europe would trust that a Trump-led America would come to their defense? Would Vladimir Putin place any credence on Article 5 if Trump was in the White House?

Where would this leave Canada?

The NATO country that would be really left out in the cold by a period of Trump-inspired isolationism is Canada.

The Great White North has a history of stepping up to defend the rule of law and the international order. It did so recently when it signed on to support Operation Prosperity Guardian, the maritime task force aimed at disrupting Houthi attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea. But times have changed since the great days of Canadian peacekeeping in the 1960s and ‘70s: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was forced to concede that Canada could not take on an operational role in the Red Sea because it had no ships or planes in the region.

Support was limited to three Canadian analysts – and lots of tea and sympathy.

This is a recurring and embarrassing theme for the Canadian military. Last year, it politely declined to take part in NATO’s largest-ever air exercise because its jets and pilots were involved in “modernization activities.”

The Canadian Forces have just announced they will take part in a massive NATO exercise, Steadfast Defender, aimed at demonstrating to the Russians the alliance’s ability to conduct sustained multi-domain defense operations for months. But Canada’s commitment, which will likely stretch resources to breaking point, will only comprise 1,000 personnel, one frigate, a couple of helicopters, and a tank squadron.

Oh Canada … and the odd-day defense plan

At home, meanwhile, the warnings about the precarious nature of Canada’s military have been sounded from the very top. Vice-Admiral Angus Topshee, the commander of the Royal Canadian Navy, said the navy could fail to meet its readiness commitments in 2024 and beyond.

Departmental reports reveal a 16,000-position shortfall in personnel, and lack of equipment meant the percentage of the fleet that was serviceable for training and readiness requests was 51% in 2022/23. The equivalent numbers for the land and aerospace fleets were 56% and 43%.

In essence, the Canadian military could only defend Canada on the odd days of the week.

The malaise is well-documented. The land forces cannot defend themselves against tanks, drones, or aircraft, and there are not enough old Halifax class frigates to live up to commitments to NATO and the new Indo-Pacific strategy. Canada’s four Victoria class submarines are 40 years old and rarely at sea, while its CF18 jets are also four decades old and, despite upgrades, considered operationally obsolete.

The Canadian Forces have ordered 88 F-35s and 15 new frigates. But there are problems with both: The stealth jets took a decade to purchase, and the first plane won’t be delivered until 2026 at the earliest, while the ships are over budget and won’t start arriving until well into the next decade.

The US Navy paid around $1.66 billion for each of its Constellation-class guided missile frigates. Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Office has estimated each Canadian frigate will cost around $4.2 billion because of bells and whistles requested by the Canadian Forces (they are not the same ship, but critics have pointed to the cost overruns and asked why Canada didn’t simply try to purchase from the US.)

Defense shortfalls and a glimmer of hope

Canada’s capacity issues have not gone unnoticed in Washington. Leaked Pentagon documents said “widespread defense shortfalls have hindered Canada’s capabilities,” casting doubt on whether it could mount a major operation while maintaining a NATO battle group in Latvia and providing aid to Ukraine.

President Joe Biden is said to have been pleasantly surprised when he visited Ottawa last March and found that Canada was prepared to pay its way on modernizing the North American Aerospace Defence Command, aka NORAD.

Under the deal signed by Trudeau and Biden, Canada will contribute $29 billion over 20 years to pay for two of six Arctic radar installations and to fund infrastructure like hangars and runways to allow the F-35s to operate in the Arctic.

But it seems that on the defense file in Ottawa, every step forward is matched by two backward. The Pentagon intelligence leaked to the Washington Post said Trudeau told NATO officials Canada will never reach the 2% target. Since then, the Liberal government has indicated hundreds of millions of dollars in absolute cuts to defense spending.

Defense Minister Bill Blair has talked about the need to spend more to boost military readiness and capacity. But at the same time, the federal government is under pressure to spend billions of dollars on a national pharmacare program to ensure its allies in Canada’s third party, the New Democrats, continue to prop it up in the House of Commons.

Meanwhile, soaring interest rates mean Ottawa is now spending more servicing its debt than it is contributing towards health spending.

Pockets, politics, and persuasion

The key measure of any Canadian government is how it manages the Canada-U.S. relationship, regardless of whether it agrees with the White House. If Trump is elected president, and NATO allies are to have any prospect of persuading him not to blow up the alliance, they have to offer at least the veneer of self-sufficiency.

The impression Trump has at the moment is that Canada and many of its allies have short arms and long pockets, leaving him, like a sucker, to foot the bill.