On Sunday, far-right parties made historic gains in elections across the European Union, leading French President Emmanuel Macron to dissolve France’s Parliament and call new elections, setting the stage for a crucial showdown with nationalist Marine Le Pen.

Across the Channel, in the United Kingdom, likely future Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s Labour Party last week promised to cut migration to that country, aiming to prevent the flailing Conservatives from scaring voters away from Labour in July’s vote.

US President Joe Biden, who has no choice but to respond to the shift in opinion with an election on the way, last week signed an executive order to shut down asylum requests at the US-Mexico border when there are too many claimants, part of a desperate-looking attempt to neutralize an issue that has been helping Republicans portray him as soft on “illegals.”

The same thing is happening wherever politicians are looking for votes. Even immigrant-friendly Canadian Liberals have capped the number of foreign students welcomed in the country in response to a housing crisis.

Missionaries for dinner

In a way, this is just politics. When an issue creates energy for one political party, other parties look for ways to siphon off some of that energy. As American journalist HL Mencken put it, “If a politician found he had cannibals among his constituents, he would promise them missionaries for dinner.”

And there is little doubt that growing constituencies across the democratic world want fewer migrants.

In the UK, where thousands of paperless migrants are crossing the English Channel in small boats every year, 29% of voters say immigration is an important issue, a six-year high.

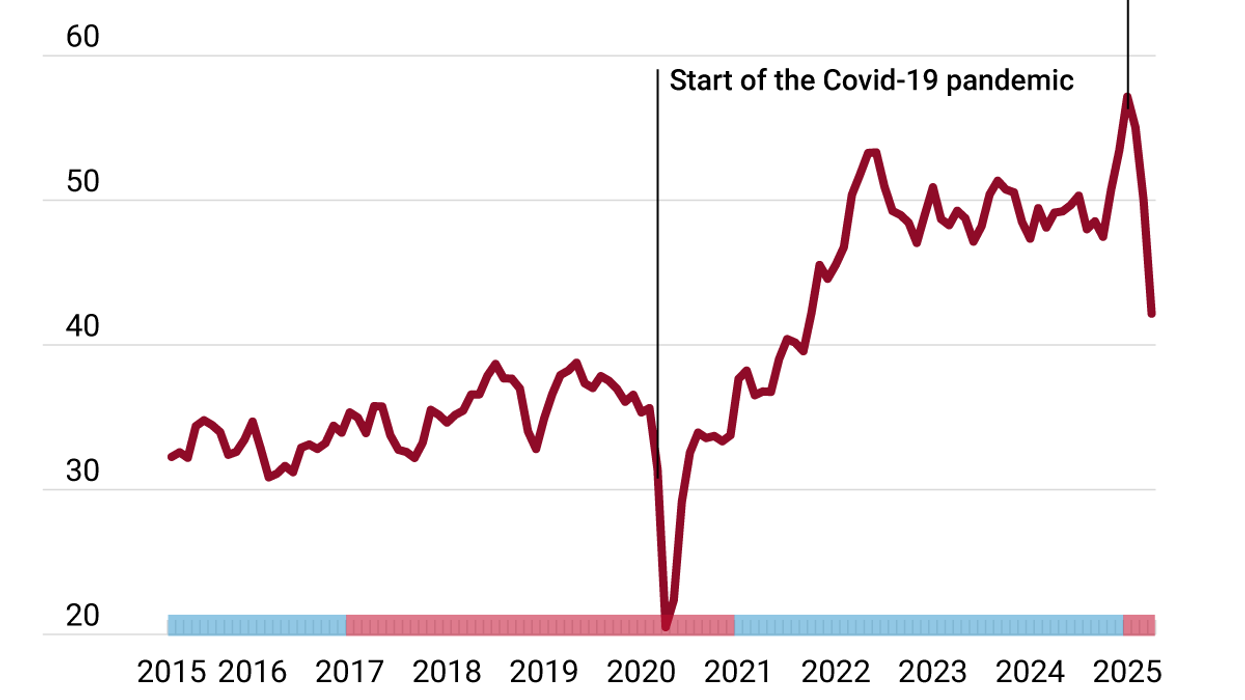

In the US, 41% of voters want immigration decreased, the highest number since 2014.

A similar shift in public sentiment is taking place across Europe, with young voters more strident than their elders in many countries.

Perception versus reality

This change in public opinion, which shows no sign of flagging, is already affecting policy. The largest bloc in Europe — the centre-right European People’s Party — has stolen votes from populist rivals to the right by adopting tougher anti-migration policies, which led to a new immigration pact before last weekend’s election. If they had not done so, the far right would likely have done even better.

This is the way democracies respond to shifts in public opinion, but there is reason to wonder if anti-immigrant sentiment is grounded in reality.

Migration is up in Europe, the United States, and Canada, but the reaction is more intense than during similar previous movements, like the huge wave of migrants who streamed into Europe when they were displaced by war in 2015. The number of irregular migrants to the US has remained stable since 2017, since many migrants return to their home countries after they save enough money.

So why has opinion shifted? Are people really responding to personal experiences with newcomers, or has the media and political environment changed?

‘Wrong choices’

Entrepreneurial populist parties in Europe and Republicans in the United States, along with their friends in the media, are finding ways to blame migrants for crime, even though the crime rate among migrants is less than half that of native-born citizens. This makes sense since most of them come north to work and can’t afford to jeopardize their precarious status.

But in the US, as polarization rises, many voters are increasingly taking their cues and forming opinions along tribal lines.

In Canada, the situation is more complicated, because Justin Trudeau’s immigration policies did worsen a housing crisis, leading to a sudden surge in anti-immigration sentiment. Last week, he agreed to pay $750 million to Quebec to help cope with the increase in migrants, which led British Columbia to complain.

Some voters may have legitimate reasons to complain, but polling shows that there is a strong correlation between negative views of immigrants and people who are misinformed. Research suggests that large numbers of voters believe in anti-immigrant conspiracy theories, like the “great replacement theory.” (For a deep dive into how conspiracy theories have infiltrated politics, check out GZERO’s conspiracy theory immersive experience here).

“Half of this is driven by ordered populism and disinformation,” says pollster Frank Graves, of EKOS Research. “That’s where we should be concerned that we don’t make wrong choices because those people who are running the political bandwagon … they don’t want to rationalize and manage better. They want to shut it down. They want to pull up the drawbridge. They don’t want any immigration.”

Both Trump and far-right European parties are promising deportations, which would ultimately hit voters in the pocketbook. For demographic reasons, immigration is vital to the economies of the prosperous democracies. There is reason to think, for example, that some of the surprising resilience of the US economy in the last two years was because of higher-than-expected inflows of people.

Politicians have no choice but to respond to changing public sentiment, and if citizens want higher walls, they will get them. But it’s not clear that voters in the rapidly aging West understand what that might cost them.