Housing mania is gripping the United States and Canada – with millions wanting but unable to find an affordable place to live.

For years, both countries have faced a growing housing crisis. The pandemic exacerbated the struggle, and only now are governments starting to take the problem seriously. Still, securing affordable housing remains a daily struggle for would-be buyers, renters, and a growing number who are either homeless or under-housed.

In February, the median home price in the US actually fell to $400,500, a decline of 7.6% annually, but housing remains unaffordable for the majority of the country. In December, a mere 15.5% of homes were considered affordable (mortgage payment no more than 30% of monthly income). A recent poll found that around half of aspiring buyers said they can’t afford a down payment and closing costs, though a mere 13% of would-be buyers said there was “nothing” keeping them from buying. This suggests that even those who might be able to afford a down payment face other challenges in the market. High mortgage rates, around 7%, “historically” low stock, and a lack of targeted rental and non-market units are keeping homes out of reach for Americans.

With homebuilders waiting on lower interest rates to initiate new builds, pressure on the market may grow in the short term. Housing starts were down in March, nearly 15% below February and 4.3% lower than a year ago.

In Canada, it’s even worse. Last month, the benchmark price was a whopping CA$720,000, up 2% over February with mortgage rates hovering between 5 and 6%. Homeownership now costs nearly 63% of the median household income, up from 35% in 2002.

High housing costs are also driving up inflation – as in the US – and the country also faces a supply shortage. In 2022, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation said the country would need 5.8 million new homes by 2030 to reach affordability. Yet, new builds fell in March, down 7% from February, and the six-month trend is also down, which means the country isn’t building nearly enough housing. There is one exception: British Columbia, with starts up 27% in Vancouver, as the province pushes new builds through a series of measures, including zoning reform to push beyond a focus on building single-family dwellings and pro-density minimum building requirements.

Why are houses so expensive?

Prices are high thanks to high demand and low stock, as usual, but there’s more to it. There’s also a lack of political action to build or encourage the building of housing people need where they need it – for instance, non-market units, purpose-built rentals, multiplex units – which is keeping stock low for segments of the population, including younger buyers and lower-income earners.

Ottawa ceased its involvement in building social housing in the 1980s and 1990s, which hasn’t helped. The US has long been a laggard on social housing, though in recent years some municipalities are starting to build publicly owned units.

Exclusionary zoning – or “not in my backyard” NIMBY-ism – has been another hurdle in both countries, with cities fighting the density necessary to build at scale and homeowners keen to protect their home values by keeping new housing out. A jump in the number of newcomers in Canada, about 471,000 last year, also contributes to market pressure.

Labor shortages are also hampering new builds in both Canada and the US, with the latter still slowed by the legacy of the Great Recession, which did more damage stateside than up north.

And then there’s the elephant in the room: the financialization of housing through which big institutional investors dominate the market looking for returns on their capital. This pernicious problem stems from seeing houses as assets first and foremost, a source of maximized profit, which invites speculation and market dominance by institutional investors who seek to inflate prices. Smaller investors, meanwhile, simply buy and flip properties.

Thinking of housing as an asset also means that individuals may see their homes as investments for retirement. Housing policy expert Carolyn Whtizman says “since the 1970s, the federal government has been treating housing, particularly ownership housing but more recently multifamily apartments, as the primary investment vehicle for retirement.”

“Housing in the US has always been an asset for the middle class,” says Noah Daponte-Smith, an analyst at Eurasia Group. “Your house is your primary retirement savings vehicle.”

Housing investors and those who rely on their homes for retirement planning want, even need, higher prices, which leaves millions priced out of the market or stretched to the brink.

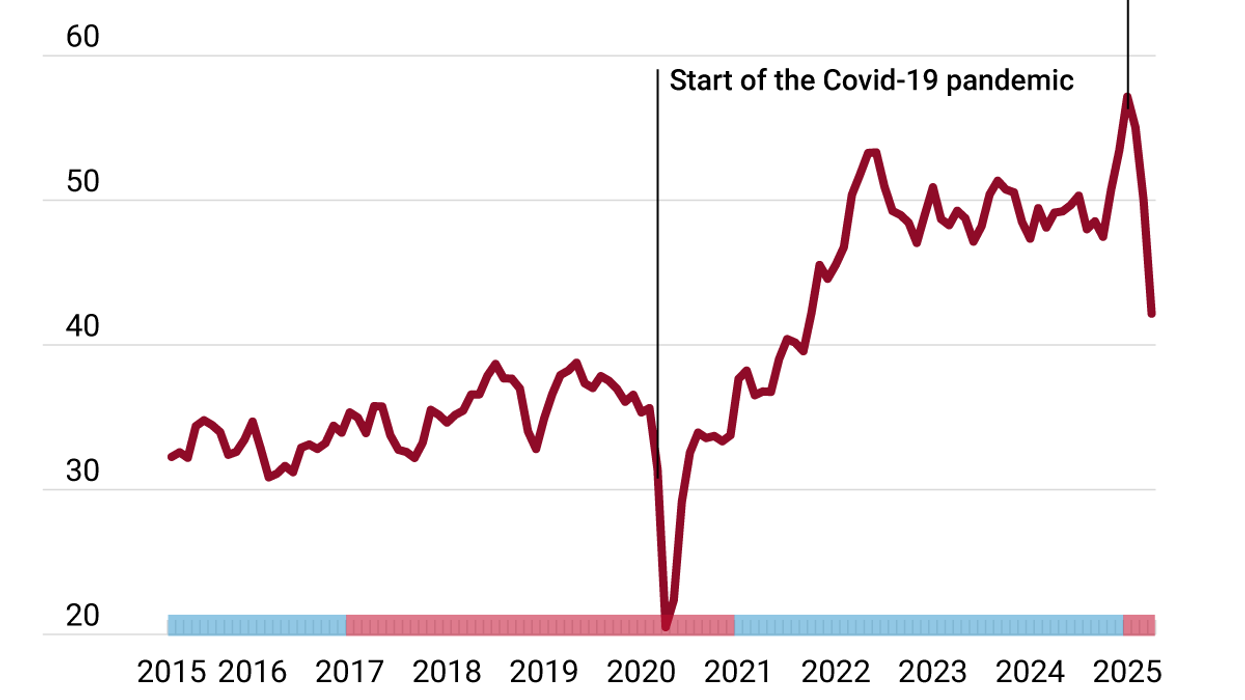

In Canada, the share of investors and repeat buyers in the market has risen precipitously compared to first-time buyers, with investors accounting for 30% of purchases last fall. In the US, first-time buyers make up a similar share of the market at 32%, and recent data suggests institutional investors could make up as much as 40% of the single-family detached home rental market in the next five years or so, which means higher prices for renters and buyers alike.

What’s going to make housing affordable?

Solving the housing crisis will take years of commitment to a number of measures. Whitzman says Canada needs a period of stable house prices and rising incomes to produce an affordable market, but it also needs government involvement in building or incentivizing stock that matches the needs of buyers and renters at various price points. The same is true in the US.

The other side of the equation is income – namely, people need higher salaries. Half of Canadians now live paycheck-to-paycheck, and a whopping 78% percent of Americans are in the same boat, which leaves no room for saving for a down payment.

Stabilizing requires efforts and cooperation by governments at the national, state/province, and local levels. One approach could be ending the capital gains exemption on the sale of a principal residence to dampen demand, just as, according to Paul Kershaw of Generation Squeeze, taxing home wealth and using the cash to build affordable housing would have a similar effect while increasing stock.

What’s being done now?

In recent years, and especially in the last few months, the Trudeau government has awoken to the need to go all-in on housing. Its 2023 Housing Accelerator Fund helps municipalities build homes, trading federal cash for national building goals, including upzoning, transit accessibility, and affordability. The fund is expected to generate 750,000 new builds in the next 10 years, and so far the feds have greenlit 179 local applications.

In Canada’s federal budget, tabled on Tuesday, the government committed to several measures focused on housing affordability to build what it says will be 4 million homes by 2031. Those include longer mortgage amortization periods, $15 billion for construction loan programs, $6 billion in infrastructure funding, and buyer tax breaks. It also promised to “restrict the purchase and acquisition of existing single-family homes by very large, corporate investors,” but those details are to be determined in the fall after consultations, and the promise itself is full of asterisks, such as “existing” and “very large.”

Stateside, Daponte-Smith points out that while there is a housing crisis, “especially in major metro areas,” no national housing strategy exists. Instead, housing policies are “determined at the state and really even at the local level,” which means that every builder has to deal with a different set of local laws and zoning codes that control what they can build and how expensive it will be.

The Biden administration is increasingly aware that it needs a housing strategy. In March, the White House announced the latest in its housing affordability plan, which includes pressuring Congress “to pass a mortgage relief credit” worth $5,000 a year over two years along with $25,000 as a cash grant for down payment assistance for first-time buyers. On the supply side, the administration is also calling on Congress to boost new builds with builder tax credits and announced grants for new builds of affordable units for buyers and renters.

Electoral consequences?

Both governments are under pressure to deliver affordable housing but are hampered by long timelines, limits on labor and capital, the need to cooperate and coordinate across levels of government, and views that housing is an asset rather than a human need.

Voters expect the Biden administration, Trudeau government, and their state/provincial and local governments to deliver, and they’re increasingly impatient – meaning they may punish those that don’t at the ballot box.

With both Joe Biden and Justin Trudeau facing voters in November and by the fall of 2025 respectively, you can expect both men to continue working on housing affordability – to get first-time buyers into the market and rents down for those unable or uninterested in buying. But they’ll be battling an intransigent market that serves investors and incumbents, and the fact that even in the best-case scenario there will be a lead time between better housing policy and good outcomes at scale.