Welcome to this special edition of Signal, where we'll look at whether the coronavirus pandemic will strengthen or weaken populist leaders.

This edition is part of a joint project between GZERO Media and Citi that explores how global political trends affect people's lives, called "Living Beyond Borders."

-Alex Kliment

Populists and the plague

Alex KlimentYou might think that a global public health crisis would boost public trust in experts, reinforce support for international cooperation, and restore faith in the multilateral institutions leading the response. You might, therefore, assume that the coronavirus pandemic wouldn't play in favor of the largely expert-blasting, populist nationalists who have swept to power in recent years. In truth, the picture is more mixed, and populists may ultimately benefit from the pandemic upheaval. A few thoughts:

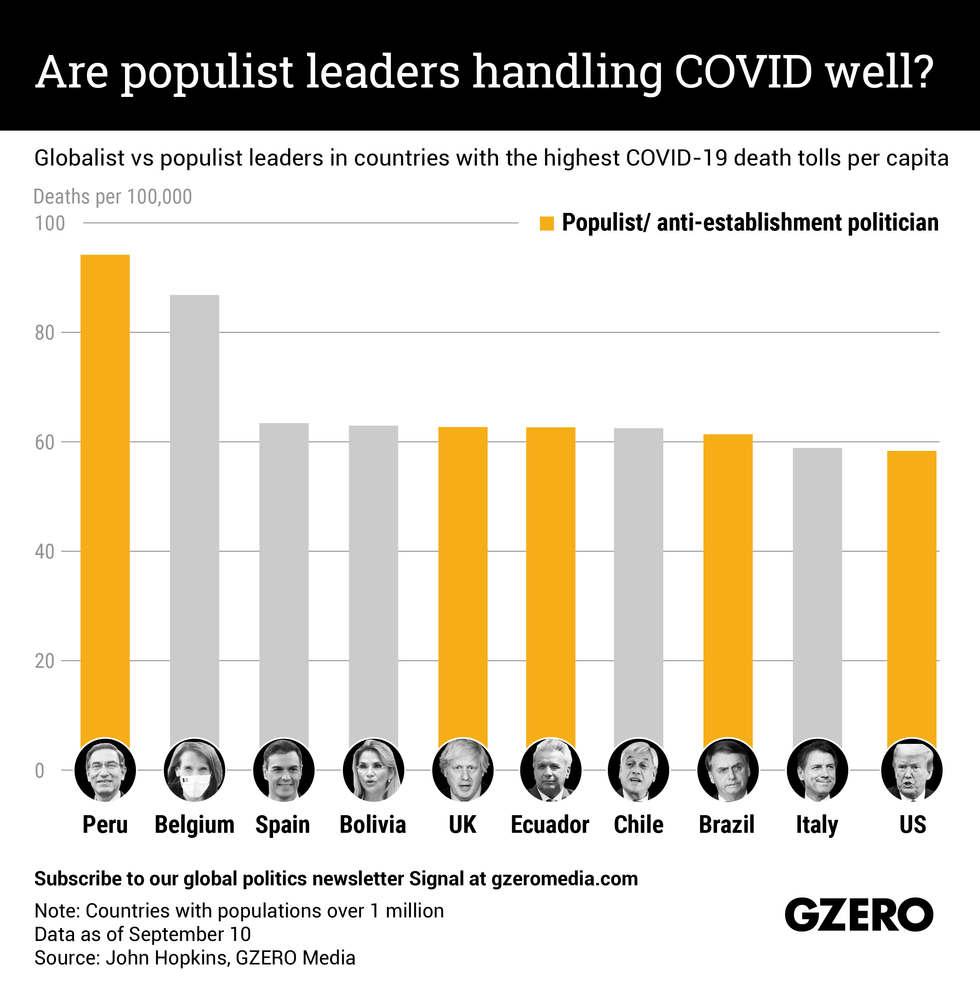

Alex KlimentYou might think that a global public health crisis would boost public trust in experts, reinforce support for international cooperation, and restore faith in the multilateral institutions leading the response. You might, therefore, assume that the coronavirus pandemic wouldn't play in favor of the largely expert-blasting, populist nationalists who have swept to power in recent years. In truth, the picture is more mixed, and populists may ultimately benefit from the pandemic upheaval. A few thoughts:First, populists aren't doing a markedly worse job than anyone else. The countries suffering the world's five largest death tolls — US, Brazil, India, Mexico, and the United Kingdom — are all led by populists, but all that tells us is that several of the world's largest countries are run by populists (bigger populations will give you a higher total number of infections and deaths). When you look at the top ten countries by death rate, populists are barely half of the group (see our Graphic Truth, below). What's more, some prominent populists, like Hungary's Viktor Orbán or Turkey's Recep Erdogan, have managed the crisis well by acting early and decisively — perhaps too decisively for the comfort of democracy watchdogs in the case of Orbán.

Even the populist leaders with large outbreaks mentioned above have avoided paying a big political price—at least so far. All these leaders have downplayed the severity of the virus, but we found that they have kept relatively stable in the polls thanks to strongly committed base voters, generally weak opposition, and shrewd exploitation of the growing economic frustration of the millions whom lockdowns have left jobless.

Looking ahead, the aftermath of the crisis may create fertile ground for populist messages. Even before the pandemic struck, concerns about inequality were reshaping politics in the world's democracies, eroding support for traditional parties and opening space for political outsiders. A Pew poll run just before the pandemic found that two-thirds of people surveyed across 34 countries thought inequality was getting worse, and more than half were dissatisfied with their political systems and job prospects.

The pandemic is going to make inequality worse. In wealthy countries, the public health and economic burdens of the crisis have fallen disproportionately on poorer or minority communities. The millions of service jobs that will come back slowest — if at all — are held mostly by lower income workers. Where schools remain closed, the impact will be greatest on children from less affluent households that lack high-speed internet access or technology for remote learning.

At the same time, on a global scale, poorer countries will suffer a bigger economic blow than richer ones. Developing countries, many of which have thin financial cushions, are suffering a triple-whammy of collapsing exports, lower remittance flows, and evaporating tourism. The IMF is struggling to coordinate adequate relief.

Populists — of both the left and the right — tend to excel in moments of economic crisis and uncertainty. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 was critical in reviving long-dormant European populist parties that would reshape politics in the years after (consider that the World Bank forecasts the pandemic's economic impact to be more than twice as severe as the one that followed the global financial crisis ten years ago).

A "social explosion" awaits. As one prominent local journalist in Latin America recently pointed out to us, even before the pandemic her region was in the throes of massive protests over inequality. Now, with the pandemic projected to plunge 45 million Latin Americans into poverty, what was already a tinderbox is practically a fireworks warehouse.

What's more, economic anguish in slow-to-recover developing countries may also prompt fresh waves of migration towards richer economies — providing ample fodder for rightwing anti-immigrant populists who will, as Viktor Orban and Italy's Matteo Salvini have done, sound the alarm about migrants who will supposedly steal jobs and spread disease.

It's hardly a foregone conclusion that populist messages will resonate loudest. The European Union, for example, agreed over the summer to a massive pandemic bailout and reconstruction package meant to blunt the appeal of Euroskeptic populists. The outcome of the US election on November 3 could yet unseat the most powerful populist in the world.

Food for thought: Will the hardships created by COVID-19 give a bigger boost to populists of the right or the left? What do you think?

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiIt's been more than six months since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Cases and deaths have continued to surge around the world — with new hotspots emerging in Latin America and South Asia. A robust global conversation has unfolded in recent months about how politicians in different countries have handled the once-in-a-generation global health crisis, and whether the anti-science views of some populist leaders — like Brazil's Jair Bolsonaro and President Donald Trump in the US —have led to worse outcomes. Here's a look at states with the highest COVID-19 deaths tolls per capita — with highlights for those governed by overtly populist/anti-establishment leaders.

Join us for six virtual events starting on September 23

Citi Private Bank

Citi Private Bank'Regeneration' is a mind set and collection of practices which bring a different framing to the moment we find ourselves in. Rather than asking how can we bounce back from the crisis, this approach asks how we might create a system that can evolve, learn, and respond more effectively to the complex challenges that we face now and in the future.

The Graphic Truth

Carlos Santamaria

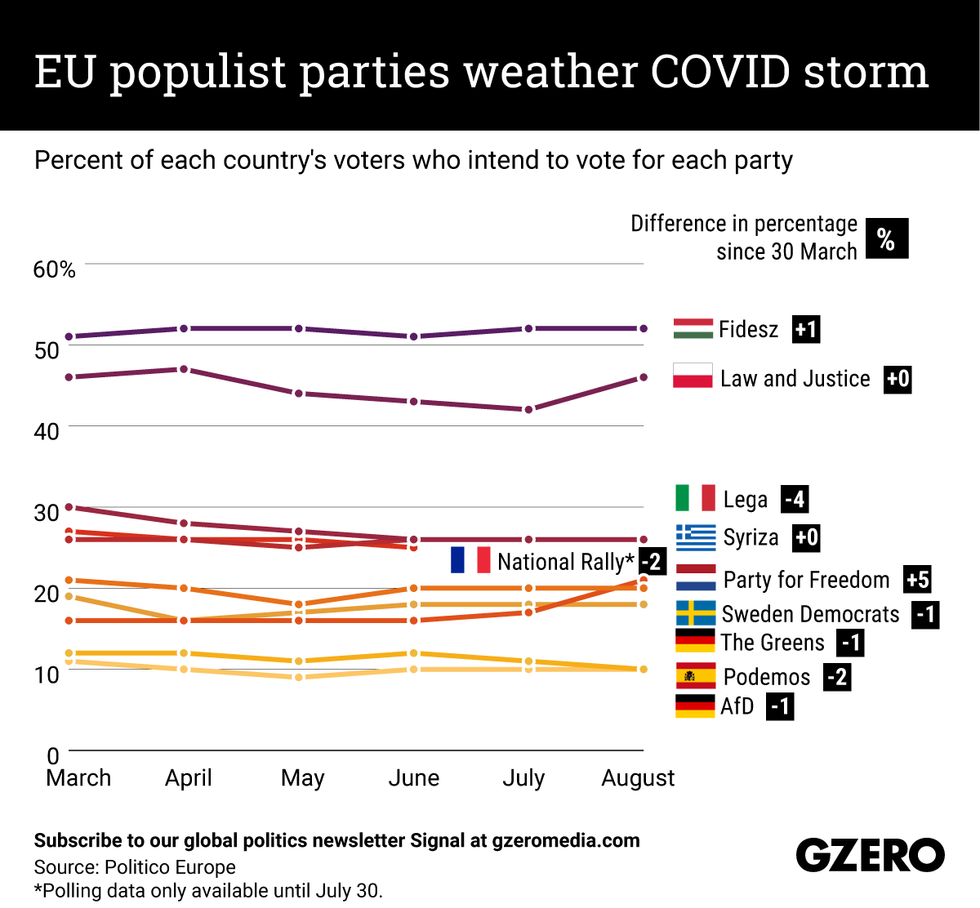

Carlos SantamariaBefore the coronavirus hit Europe in March, mainstream political parties were struggling to contain the rise of populist and anti-establishment forces. Did COVID-19 change that trend? While a handful of major populist parties have lost some support and a few others have gained in the polls, voter intention for most of these forces has not in fact changed significantly. We take a look a how ten EU populist parties have polled over the past six months.

PODCAST: Is Globalization Cancelled?

Globalization came with a big promise: that the swifter movement of goods, investment, and people across borders would raise the economic tide and lift all boats. But decades into the experiment and months into the worst global crisis in a lifetime, nationalist populism remains on the rise. In this critical moment, is there a way forward that harnesses the economic power of globalization while more equitably distributing its benefits? This episode of the Living Beyond Borders podcast features Ian Bremmer, President of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media, along with Citi's Global Chief Economist Catherine Mann in a conversation about the future of globalism moderated by Meredith Sumpter. You can find it here.

What We're Watching: COVID elections, jobs lost forever, Africa's COVID enigma

Willis Sparks

Willis SparksElections continue despite pandemic: Nearly two-thirds of Americans disapprove of President Donald Trump's handling of the coronavirus crisis. Americans, like voters everywhere, are at odds on many issues these days. But a Trump victory in November would signal that voters aren't ready to blame political leaders for the coronavirus' impact while a loss would make him the world's first COVID-19 political casualty. There are more upcoming coronavirus election tests. Regional elections in Italy later this month will test the strength of that country's wobbly coalition government. Hard-hit Iran will hold a presidential election next June—though it's not clear how far the clerical establishment will go to limit voter choices—and the government's pandemic response will shape broader views of its competence. Voters in virus-ravaged Peru will have their say in April 2021, and Mexico will hold congressional elections in July. A power transition in Germany next year will allow voters angry over COVID-19 restrictions to air their grievances.

Why COVID will erase some jobs for good: Many who've lost jobs during the pandemic will return to work once vaccinations bring COVID-19 under control. But there are three reasons why many others will find their jobs are gone for good. One, some businesses will not survive the economic stress. Two, some employers will see layoffs as a chance to lower labor costs as their companies struggle to restore profitability. Three, COVID-19 has increased incentives for many businesses to accelerate the process of replacing workers with machines that work around the clock and don't take sick days. These inter-related problems will leave large numbers of people in financial trouble in both developed and developing countries. International lenders like the International Monetary Fund will be hard-pressed to answer every call for help from cash-strapped governments, and taxpayers in wealthier countries will demand their governments focus spending on recovery at home rather than bailouts abroad.

Africa isn't out of the woods (yet): So far, the African continent has suffered far fewer COVID infections and deaths than many feared. There are many theories — some of them contradictory — of why that's the case. Some credit demographics: More than 60 percent of Africans are under 25, and young people are believed to weather the virus with fewer bad effects. Some hypothesize that the continent's lower population density makes a difference, while others ask whether crowded urban slums in some countries have exposed many residents to coronaviruses of the past, bolstering immune responses to COVID-19. But these are just theories, and Africa isn't out of the woods. As home to many of the world's poorest countries and people, what happens in Africa will help shape international attitudes toward globalism and whatever barriers might prevent the free flows of people, because there's no region where hardship can push more people from their homes and across borders.

Hard Numbers: Nicaragua’s (unofficial) COVID death toll, economic pessimism, social media infodemic, pandemic "denialists"

Carlos Santamaria

Carlos Santamaria2,707: Nicaragua's (unofficial) COVID-19 death toll has risen to 2,707, according to the Citizen Observatory, an independent body that disputes the official government figure of only 137 fatalities. Daniel Ortega — the country's authoritarian populist president and one of very few world leaders who initially refused to impose a lockdown — has been widely criticized for his handling of the pandemic.

67: A median 67 percent of people in 14 industrialized economies (mostly) governed by establishment leaders in Asia, Europe and North America believe the economic situation in their countries will be worse a year from now, according to a new Pew Research poll. South Koreans are the most concerned, while Danes and Swedes are the least worried about next year's economic outlook.

2,311: Researchers from Bangladesh, Australia, Thailand, and Japan identified a total of 2,311 reports of COVID-19 misinformation on social media between December 31 and April 5. Examples include conspiracy theories about the coronavirus contaminating poultry eggs, as well as that COVID-19 is a bioweapon created by Bill Gates to boost vaccine sales.

12: Although populist leaders are widely perceived to have downplayed the threat of the coronavirus, a new report by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change argues that twelve out of 19 leaders identified as "populist" actually took the pandemic seriously, although some later reacted with illiberal policies. Those classified as "denialists" are the leaders of Belarus, Brazil, Mexico, Nicaragua, and the US.

Follow us on Twitter and Instagram. If a friend sent you this email, you can subscribe here.

This edition of Signal was written by Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. Graphics and art by Gabriella Turrisi and Annie Gugliotta.