Throughout much of 1968, the government of Czechoslovakia, led by Communist Party chief Alexander Dubček, carried out an extraordinary and fateful experiment.

Believing that more economic, political, and cultural openness would reinvigorate the communist project, Dubček set about constructing what he, and the intellectuals who backed him, called “socialism with a human face.” Censorship eased, more competitive elections were proposed, economic decisions would be cautiously decentralized.

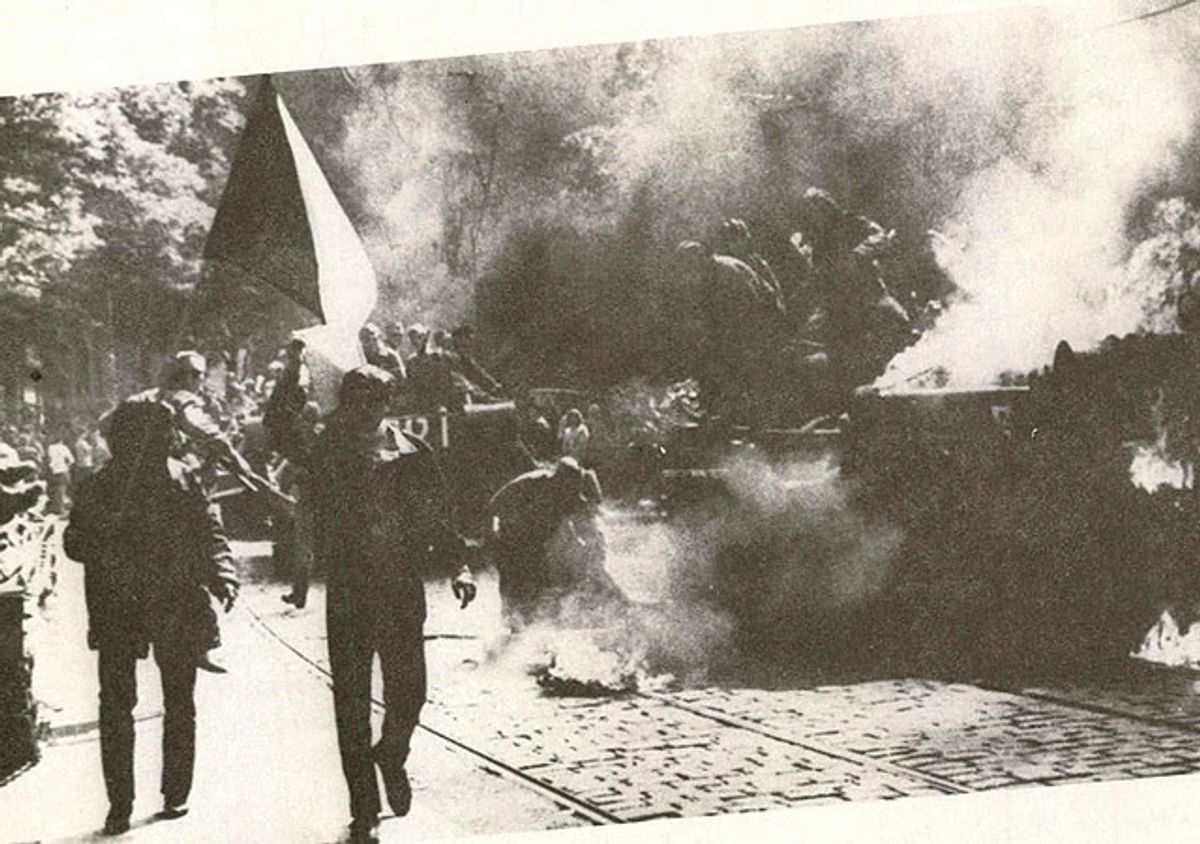

Moscow was incensed. The Kremlin saw Dubček’s idealistic tinkerings with Soviet orthodoxy as an existential threat to the Kremlin’s hold over the Eastern Bloc. And so fifty years ago last night, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev sent half a million troops into Czechoslovakia to snuff out what had become known as “the Prague Spring.” Dubček was arrested and deposed. The Soviets would stick around, heavily resented, for two decades.

Why did it matter back then? The invasion made it clear that no reform of socialism was possible, marking a turning point at which many intellectuals behind the Iron Curtain made the perilous leap into outright opposition. One of those intellectuals was a young Czech playwright named Václav Havel. It would take nearly a quarter of a century for the work of those dissidents to bear fruit, but the seeds were sown in August of 1968.

Why does it matter now? For years the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia confirmed for many in Central Europe that a chronically imperial Russia would never fully respect their sovereignty. After communism fell in 1989, that fear drove them to seek EU and NATO membership. But today, amid growing friction between the region and Brussels over European values and rules, polls show that close to 40 percent of Czechs and Slovaks, along with more than 20 percent of Hungarians and Poles, say Russia can be a valuable partner in pushing back against an overbearing EU.