Around the world, national governments in countries that are home to large diasporas or immigrant populations face the challenge of expanding people’s inclusion (by conducting official business in many languages) without encouraging the fragmentation that can result when people don’t need to learn the primary official language. Here are two stories in that key:

Putting Arabic in French Schools…

In a controversial bid to blunt the appeal of Islamic extremism in his country, French President Emmanuel Macron’s administration is pushing a proposal to teach Arabic in public elementary schools. At the moment, French citizens of Arab origin who want their kids to learn the language have few options beyond local mosques, which teach it in a religious context. Amid concerns that mosques in poorly-integrated neighborhoods have become fertile recruitment grounds for radicals (ISIS has drawn more recruits from France than from any other Western country), Macron wants to provide an alternative, government-sponsored option. But critics of the idea say that allowing kids to study Arabic in French schools will just make it harder for them to integrate in a society where French is the official language. And lack of integration among minority groups in France is seen as a contributor to radicalization in the first place.

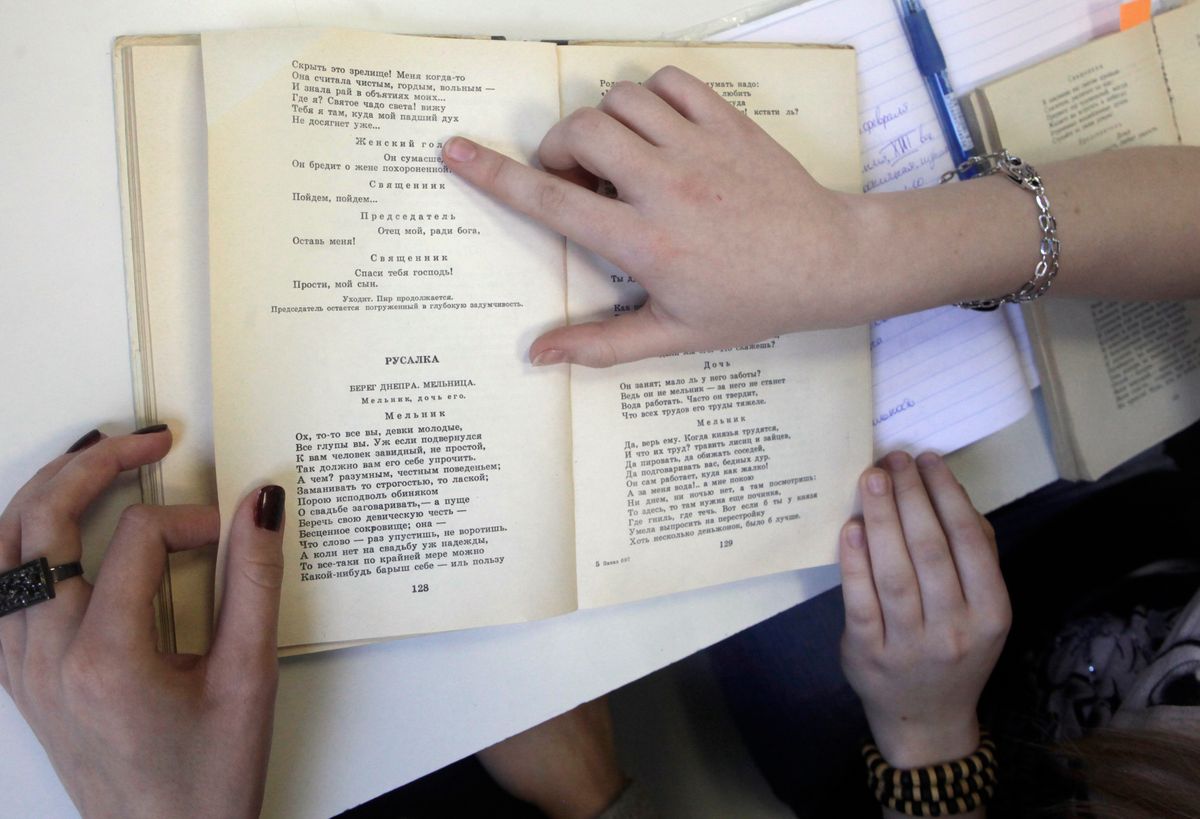

...while taking Russian out of Latvian ones.

The tiny Baltic nation of Latvia has courted controversy by banning the teaching of Russian in elementary schools. The government sees the move as a necessary step to reinforce a sense of unity and nationhood in a country where only 60 percent of citizens are ethnic Latvians. By way of background, Latvia – whose own language has nothing to do with Russian – was forced into the Soviet Union during World War Two, and for decades thereafter the population and school system were Russianized under Soviet control.

After the USSR fell apart in 1991, many Russians (and other ethnicities who never learned Latvian) stayed in the newly independent country rather than “return” to Russia. They are understandably upset about the new law, as is Moscow, which has blasted the “odious” measure. The role of Russian in Latvian public life has long been a contentious issue – a 2012 referendum shot down a proposal to make it the country’s second official tongue. And the plight of Ukraine now looms large over the entire debate – in 2014, after the pro-Russian government in Kyiv was overthrown, the new authorities immediately passed a bill limiting the use of Russian. That was one of the main pretexts for the Kremlin’s decision to annex Crimea and back rebels in the East. Russia, President Putin said, reserved the right to defend “Russian-speakers” everywhere.