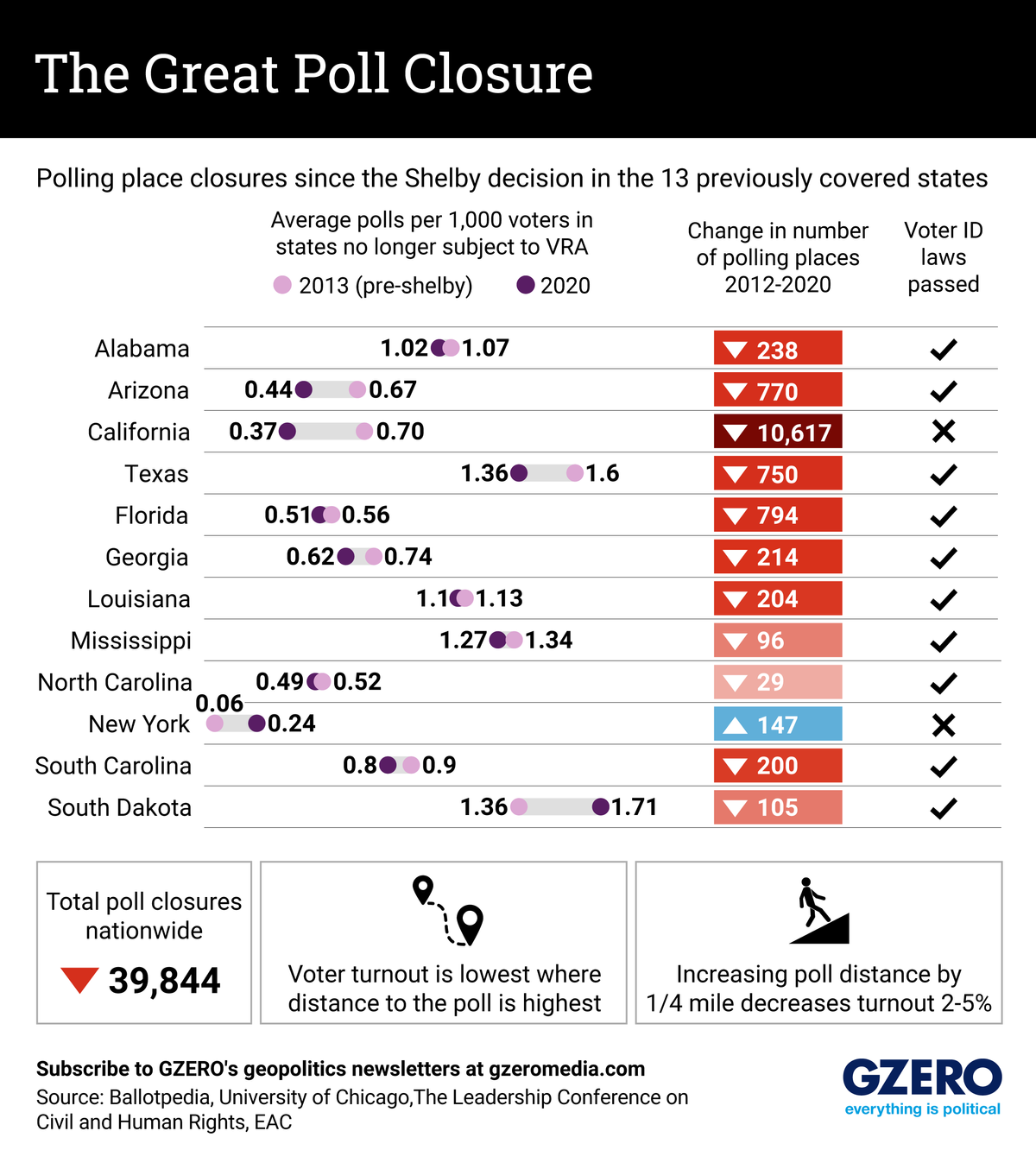

In 2013, the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in the case Shelby v. Holder, fundamentally transforming voting in the US.

39,844 polling places have closed down in the years since, primarily in communities of color. Fewer places to vote means it is harder, and sometimes impossible, for voters of color, with disabilities, or low incomes to vote.

The Shelby decision: In 13 states with a history of racial discrimination, the Voting Rights Act required that any changes to election administration be reviewed to ensure they did not disadvantage minority voters. The Shelby decision took away this oversight.

The effects were immediate. Within 24 hours Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama implemented voting laws that had been previously ruled discriminatory.

Voter ID laws:Studies have found that strict photo ID requirements to vote depress turnout and disproportionately harm voters of color.

In Kansas, over 63,000 people were blocked from registering to vote after the state implemented its ID law, most of whom were eligible voters. In Georgia, an "exact match" law resulted in over 51,000 people being flagged, 80% of whom were Black, Latino, or Asian. Under the law, discrepancies like having “Tom” on a voter registration form, but “Thomas” driver’s license would be grounds for voter status to be suspended.

Poll closures: Without federal oversight, polls have been closed in communities of color en masse.

In Arizona's largest county, Maricopa – where four in ten residents are people of color – polling places were reduced by 70% after Shelby, leading to voters having to wait up to five hours in 2016.

In the absence of VRA oversight, communities of color who fear they are being disenfranchised have limited legal recourse.