Did Hamas score a big win at the United Nations, or was it actually a win for the much-maligned idea of the two-state solution?

Forgive yourself if you ignored the critical UN vote last week. Like the blaring horns on the streets of New York, many folks tune out the UN as meaningless background noise to the real action in global politics: sound and fury signifying bias. That is a mistake. The controversial May 9 vote on granting Palestine full membership to the UN bears real scrutiny. After all, in plain terms, the vote effectively means recognizing a Palestinian state.

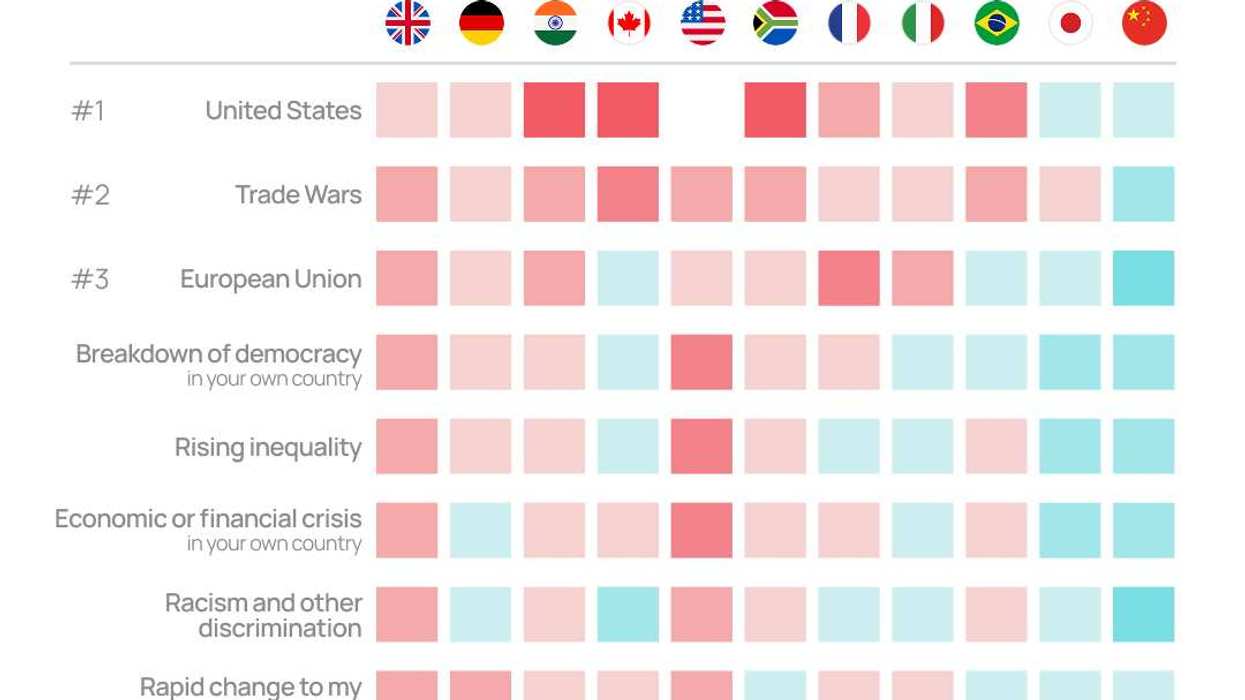

The vote was supported by 143 of the 193 countries that make up the General Assembly – that’s more countries supporting this idea in 2024 than the last time something like this was voted on, back in 2012. Just seven months after the Oct. 7 Hamas terror attack on Israel, Palestine has won more support, not less. And Israel is more isolated, not less. Nine countries, including the US and Israel, voted no, but this next bit is telling: 25 countries, including Canada, abstained. This signals a major shift in Canadian policy, as it has historically voted “no” alongside the US.

What changed, and what exactly was the vote saying about who would represent the Palestine state if it was granted full status– the Palestinian Authority or Hamas? Can there be a Palestinian state with Hamas playing a role? Is the current Israeli government trying to kill the idea of a viable two-state solution?

To find out, I spoke with Canada’s Ambassador to the United Nations Bob Rae.

Evan Solomon: Ambassador, 143 countries at the UN General Assembly just voted to grant Palestine full member status — essentially recognizing a Palestinian state. Canada was among the 25 countries that abstained, which is a change in policy from a hard “no.” Why the shift in policy?

Ambassador Bob Rae: Largely because we think the situation on the ground is changing so fast. We wanted to make it clear that we still favor a two-state solution, but that we also recognize that it’s going to take a lot of work for that to happen. There’s going to have to be significant changes, frankly, on both sides to get there. Most dramatically on the side of Hamas, which continues to wage war after its Oct. 7 attack on Israel, and is not, by any means, defeated. We have to be clear that there can’t be a terrorist group in charge of a state. Israel will never accept the notion of a terrorist state being granted a status in international law, and we would never do it. The only way we can proceed is if that changes.

The other thing that needs to change is the policies that are currently being pursued by the Israelis in political terms, which is refusing to countenance the idea of two states coexisting.

The argument that we’ve always made in the past with this kind of resolution is to say, “No, we can’t support that, but we want to ensure that the parties will get back to the table, and that’s where things will get resolved.” But it's clear that at the moment, the current Israeli government has no intention of negotiating anything approaching sovereignty for Palestinians. So we don’t see how we can simply vote “no” anymore. We also don’t see how we can simply say “yes” either. We don’t think we can responsibly do that either. So that’s why we’ve taken the position we’ve taken.

Solomon: Was this a position that was true before Oct. 7, or has it changed because of the attack and the aftermath?

Rae: The feeling was that you had more of a discussion going on within Israel about the possibilities of two states. However, we know that Mr. Netanyahu has never been enthusiastic and never really admitted to the possibility of a Palestinian state, and now it’d become even clearer that’s not on the table.

On the other side, I do think that there has been, in the last 20 years, a strong endorsement of the two-state position by the Palestinian Authority leadership on the political side in the West Bank, but that has not been matched by Hamas. So that’s why we changed the position from 2012.

Solomon: Back in 2012, only 138 countries voted for the resolution that upgraded the status of Palestine to a non-member observer state within the UN, but Canada voted against it. What does the increase of support tell you? Is this, essentially, a vote for the Hamas cause? Does this show that their horrifying terror attack was a strategic success?

Rae: I don’t think so. I think that this whole “reward theory” is wrongheaded. The support in the General Assembly for two states is overwhelming. If you actually read the speeches of the countries that voted no, and the countries that voted to abstain, and the countries that voted yes, the support for two states was unanimous going from the United States and Hungary and other countries that voted no to the countries that abstained like us.

Solomon: But you had countries voting yes, like Denmark, the Aussies, and New Zealanders. What does that say?

Rae: I think it is a question of asking if a Palestinian state is prepared for membership in the United Nations. Canada looked at that question and we decided it doesn’t meet the test of what it means to be a state. The state is a place that has control over a territory, and the Palestinian Authority doesn't. Now, the Palestinians say, “Yeah, we haven’t been able to exercise control over the territory because of Israel.” And that's partly true. But it's also true to say now that they don't have control over the territory because of Hamas terrorism, which they have not been able to deal with effectively or to the extent that you can say, “This is a state that's ready to go.” The point is that there's real work to be done in the creation of two states, and we've still got to get there.

Solomon: Did the vote at the UN signal that most countries are ready to recognize a Palestinian state, even if Hamas is part of the governing body?

Rae: No, I don’t think that’s the case. I really don’t. What has to be very clear is that there's no room for a Hamas state at the UN. That’s something where there’s a very strong consensus.

Solomon: But the vote doesn’t make that distinction.

Rae: That’s why I say the decision on who gets admitted to the UN is not based on high hopes. It is based on what are the realities on the ground. We have to get real about it. That's where I think Canada is not alone. Many other countries feel the same way. The real work starts now with saying: How do you get to a cease-fire? How do you get to where you want to go, which is a two-state solution?

Solomon: Is a two-state solution effectively dead?

Rae: The trouble with that argument, Evan, is that you’ve got to then say, ok, if the two-state solution is dead, then what? When you look at the other alternatives, they don’t work either. For example, if you take a “river to the sea” approach, whether it's from a terrorist position or an Israeli perspective, that doesn't work. So it's really important for people to come to grips with the fact that the most fact-based, realistic solution has got to be based on the notion of two sovereign states living side by side in security and in peace. And, one hopes, eventually in partnership. It takes a long time to get there. But if you drop the idea of any possibility of sovereignty to realize Palestinian aspirations, then you've really abandoned all hope.

Solomon: From the Netanyahu government point of view, the argument is that Hamas doesn’t even recognize Israel’s right to exist, and neither do many other countries in the region. So a two-state solution is, at best, a naive hope. At worst, a serious security risk.

Rae: All that is part of the solution. That’s all part of what needs to happen. These things can change. We've seen things can change. It's all about building the basis for change. To rule it out entirely is a mistake.

Solomon: Does Hamas, a listed terror group in Canada and the US, need to be destroyed, as Netanyahu argues, or can they evolve out of that status, and transition toward governance?

Rae: No terrorist entity can become part of a state. That’s not possible. Can terrorist groups change? History points to some examples of that. The IRA, the African National Union, which was listed in many countries as a terrorist organization. It transformed itself. It changed. But the problem with Hamas — and it is in their charter — is that it is based on the obliteration of the state of Israel. That's not something that anybody can accept. It isn't good enough to say if this and if that. We can't get into too many hypotheticals. Right now Hamas' official policy is to obliterate the state of Israel. Israel is a sovereign state and a member of the United Nations, so while Canada has strong disagreements with the current policies of the current government, that's very different from saying that we are going to pretend that Hamas is not Hamas. I mean, that would be wrong.

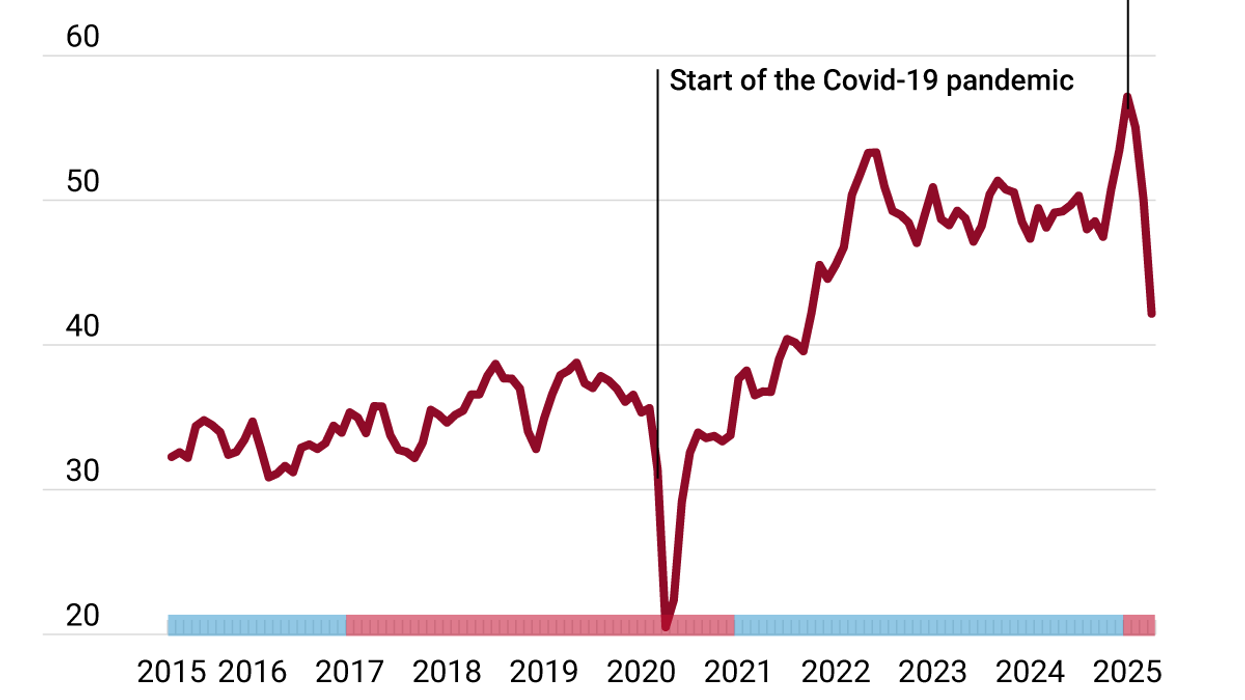

Solomon: Neither Joe Biden nor Justin Trudeau gets on well with Benjamin Netanyahu. How isolated is this Israeli government right now?

Rae: That’s a very important question. My own view is it’s not simply about Prime Minister Netanyahu or the state of Israel. Anybody with any degree of empathy would understand that the activities of Hamas – the sexual and gender atrocities, the atrocities on children and families, and the sheer brutality of the attacks on civilians – are unprecedented. It's been deeply traumatic for the Israeli people. So if you ask them, “How do you feel about two states?,” you can understand them saying, “For God's sake, don't talk to me about that until you've dealt with what we're dealing with.” You have to understand that the current disagreement that we have with Israel is not irreparable. It's not like we're stopping talking or engaging.

It’s important for everybody to be clearheaded about how we need to go forward and the work that’s involved. But any tactic or strategy that doesn't recognize the democratic rights of either the Israeli people or the Palestinian people is doomed to fail.