As NATO member countries wrangled in Vilnius this week over when and how — or if at all — to invite Ukraine into the fold, Canadian PM Justin Trudeau was thought to be lining up with Eastern European countries. Those are the ones who want the alliance to open the door to Kyiv, while the US and Germany are more cautious.

But whatever Trudeau had to say, Canada’s position did not get much attention. And why should it? NATO’s largest member by territory barely spends more money on its military as a percentage of GDP than tiny Luxembourg.

Like a dinner guest who arrives empty-handed when everyone else has come bearing wine, Trudeau is doubtless aware that others are silently judging him, and he is doing what he can to maintain appearances.

On the way to Vilnius, he stopped in neighboring Latvia to announce that Canada will increase its presence there, deploying 2,200 soldiers and 15 Leopard tanks by 2026 — a modest but meaningful contingent some 150 miles from the Russian border. The Canadian troops will no doubt be a comfort to the Latvians, but nobody should expect Ottawa to do anything else anytime soon, because the cupboard is all but bare.

Canada will struggle with its deployment. The mighty US military, in contrast, keeps 35,000 troops permanently stationed in Germany.

Other NATO members would be happier if the Canadians did more. “They’ll make welcoming statements,” says Christyn Cianfarani, president of the Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries. “But it doesn’t move the needle in any substantive way, the way our allies would like us to step up.”

Cianfarani’s association — which represents Canadian arms manufacturers — can be expected to yearn for bigger military budgets. But its laments are increasingly being amplified by other voices in the Canadian public policy world.

“Based on past decisions to not invest, we're now at the point where the rubber is hitting the road,” says David Perry, president of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute. “The government doesn't actually have the assets to do the same types of things that we used to, even just five years ago.”

Canada’s support for Ukraine is at odds with a broader NATO target. Canada has a politically powerful Ukrainian diaspora, including deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland, and Trudeau has done what he can to help Kyiv. Canada is ranked sixth — behind only the US, the EU, the UK, Germany and Japan — in terms of aid committed to President Volodymyr Zelensky.

But its overall defense spending is near the back of the NATO pack, ahead only of Slovenia, Turkey, Spain, Belgium, and, yes, Luxembourg.

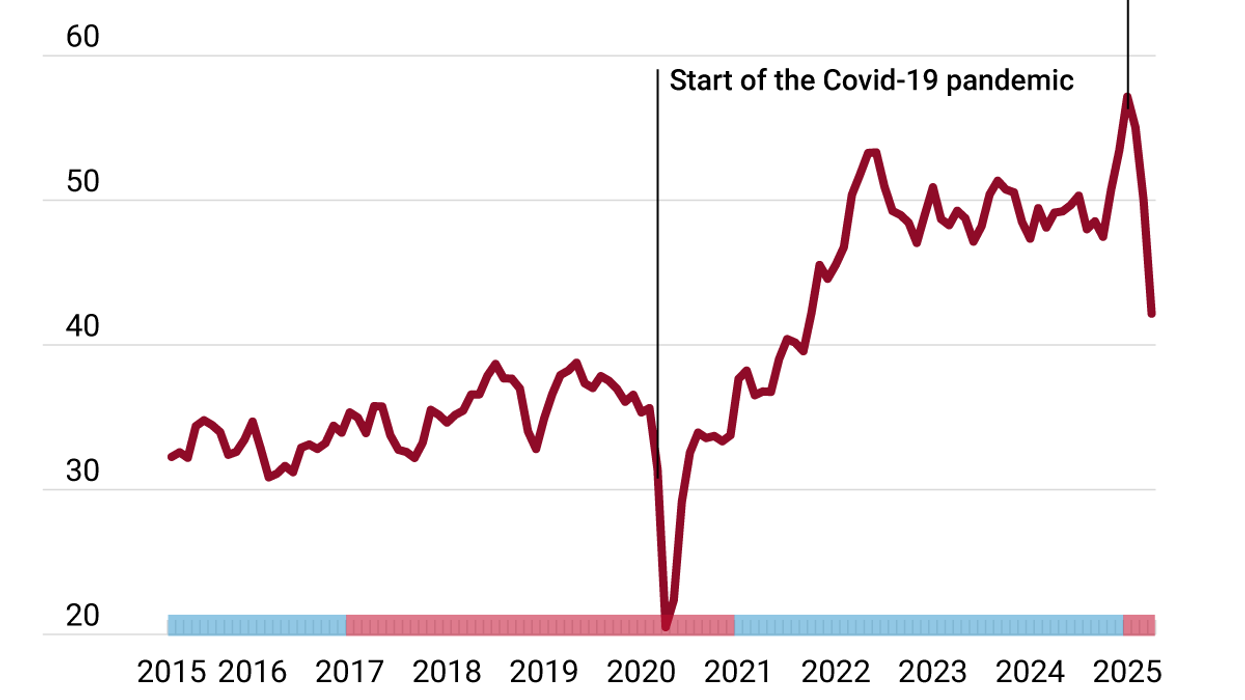

Canada’s penny-pinching is particularly striking given NATO’s own defense-spending target of 2% of GDP, which all members have agreed to. Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg has long been pressing the laggards to put up more cash, but Canada — at a measly 1.38% of GDP — is unlikely to reach the target any time soon.

What’s more, Trudeau has privately admitted to NATO officials that Canada will never get there, as we learned in April thanks to leaked documents.

Politicians and diplomats at NATO summits normally do not publicly criticize one another for underspending, at least now that Donald Trump is out of office. Yet behind the scenes, American officials are withering in their contempt for Canadian parsimony on the issue.

“Widespread defense shortfalls hinder Canadian capabilities,” the document says, “while straining partner relationships and alliance contributions.”

Many NATO partners are frustrated by Canada’s inability or unwillingness to contribute more. And it’s not just spending more on defense to meet the alliance’s target.

Ottawa has declined, for example, to lead a stabilization mission in Haiti. It had to skip a NATO air force mission in Romania this year for want of planes. The US, not Canada, shot down a Chinese spy balloon over Canada this year.

Without nuclear submarines, Canada is unable to have a military presence under the Arctic ice. And without money for subs, it was excluded from AUKUS, a new defense pact with Australia, the US, and the UK.

The problems go beyond a lack of spending: The Canadian Armed Forces have difficulties recruiting personnel and procuring equipment.

The Trudeau government has begun to respond to growing dismay at home and abroad. It has promised to spend CA$40 billion to modernize its NORAD aerospace defenses, and is buying 88 F-35 stealth fighter jets for CA$19 billion. But in both cases, Canada is belatedly spending money to maintain a capacity it has long had.

“I think we should expect to receive pretty minimal credit for replacing 40 to 45-year-old fighter planes,” says Perry.

The Conservative opposition has raised the alarm and called on Trudeau to do more, but history suggests that even if they replace the Liberals in the next election, they may make similar calculations, choosing butter over guns. (Remember that the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, who Trudeau defeated in 2015, talked a good game, but under budgetary pressure, did not spend much more, so Canada has had low levels of military spending for decades.)

“There's a lot more enthusiasm on the part of Canadian political parties when in opposition to increase defense spending significantly than those parties in government have demonstrated,” Perry explains.

This is a matter of both geography and history: Canada has three vast coastlines, while Russia and China are far.

“We share a 9,000-kilometer border with the biggest military power in history, and our closest ally,” says Gerald Butts, vice chairman of Eurasia Group and former principal secretary to Trudeau. “Some people think that's freeloading; others think it's common sense. The truth is probably a mix of both.”

As the world becomes more dangerous in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine and China’s military buildup, the arguments for increasing defense spending get stronger. But polling shows Canadians are divided on the issue. With inflation making it harder to balance the books, the government is under intense pressure to spend the little cash it can spare on things that everyone wants.

For the most part, that doesn’t include the military.