Early today, police in riot gear moved against protest encampments at UCLA, taking down tents, arresting people, and removing demonstrators from campus. This came after similar actions on campuses ranging from Columbia to Dartmouth.

Where is this headed?

What started as a reaction to the Hamas-orchestrated massacre of Oct. 7 and the extent of the deadly counteroffensive by the Israeli military has now grown to encompass wider, more amorphous issues. These include everything from the validity of Zionism to the viability of a two-state solution and now, depending on where you go, climate justice, over-militarized policing, and even capitalism itself.

In the military, this would be called mission creep. That’s when a mission starts with a specific goal, but over time the scope widens so much that the initial objective is lost and the new goals become too complex to be attainable. This usually ends in failure.

“Mission creep” was coined by a Washington Post columnist in 1993 to describe the disastrous American-supported UN intervention in Somalia — the famous Black Hawk Down incident in which 18 US service members were killed. It became more prominent after 9/11 when the initial objective of wiping out al-Qaida spread into overthrowing Saddam Hussein and the Taliban, which morphed again into the idea of setting up stable democracies in Afghanistan and Iraq. Mission creep is a trap, setting impossible goals that erase the possibility of an exit strategy.

This is starting to happen with the campus protests as well. It’s not mission creep exactly. Call it protest creep – where the scope of subjects now being debated is so vast that it is starting to undermine the very real issues the demonstrators wanted to bring to light.

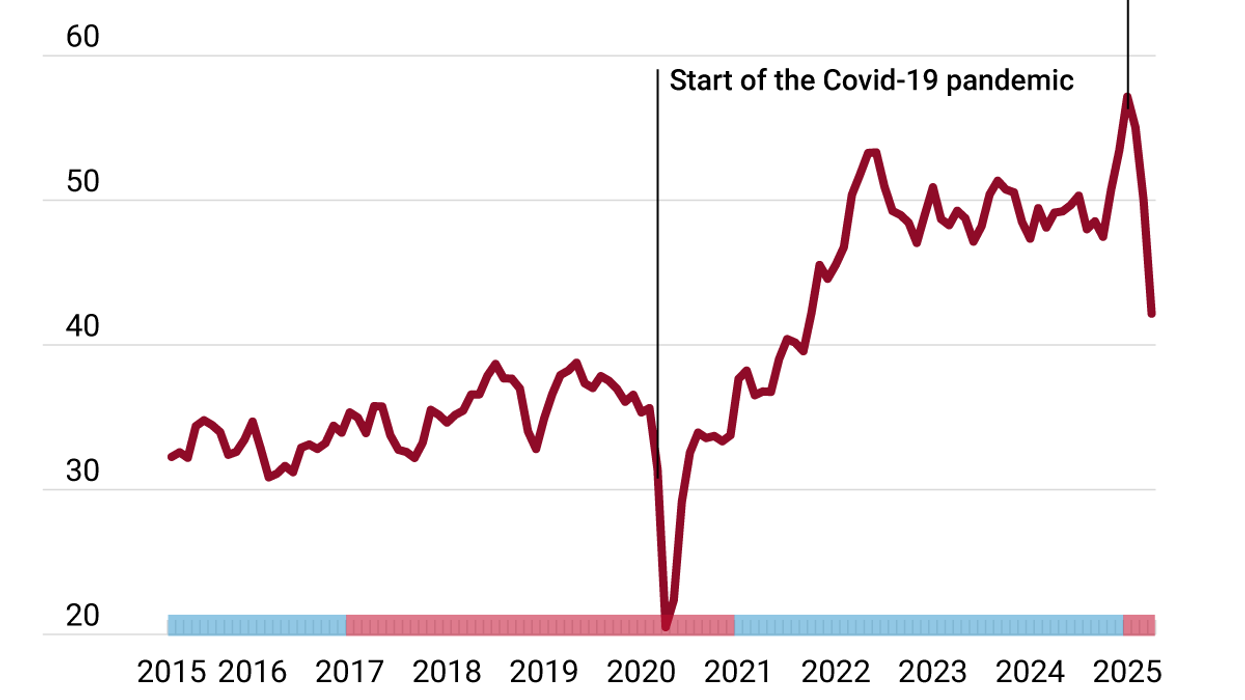

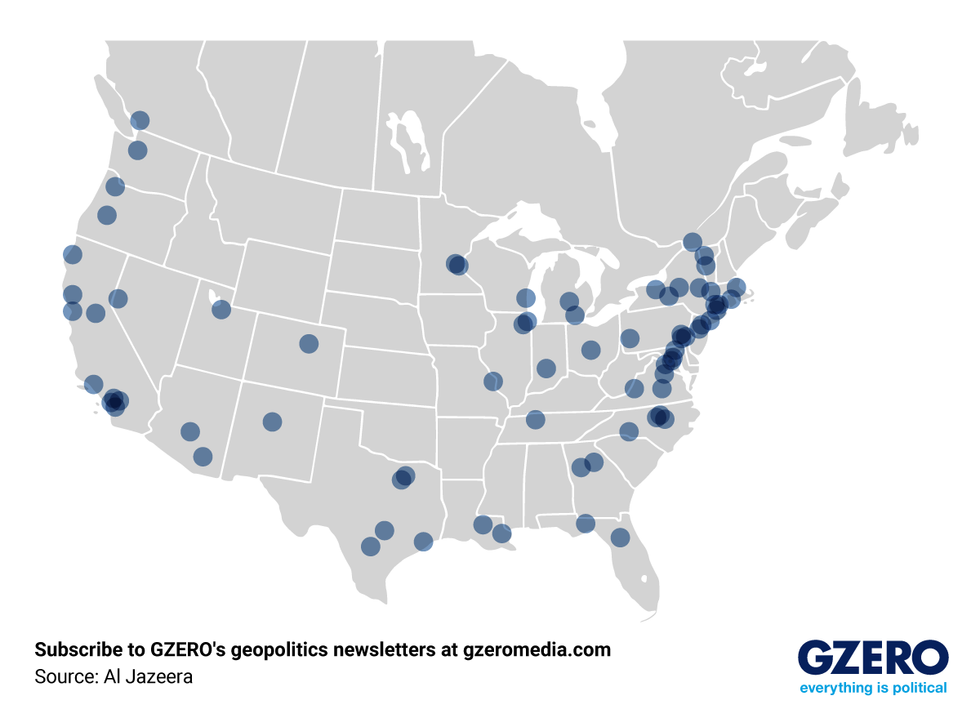

Protests are spreading to campuses throughout the US and to a few schools in Canada.Luisa Vieira

Protests are spreading to campuses throughout the US and to a few schools in Canada.Luisa Vieira

Whatever position you hold, the right to ask uncomfortable questions about Hamas’s attack or about Israel’s response is what a democracy is all about. Is the Israeli invasion of Gaza a justified response to a terror group’s massacre, as some say, or has it morphed into a genocidal war on Palestinians, as others argue?

Should universities boycott, sanction, and divest from any company doing business with Israel or support the defeat of a genocidal terror group like Hamas? These questions rightly evoke passionate responses and make some people feel uncomfortable. Of course they do. But democracies are not built to protect people from feeling uncomfortable; they are built to protect individual and collective civil liberties. Being exposed to and living with ideas you disagree with is the foundation of an open society – and frankly, one of the purposes of going to university in the first place.

That doesn’t mean there should be no red lines. For example, the space between support for the people of Gaza and criticism of Israel’s response has moved into a full debate about Zionism itself – and whether anti-Zionism is a form of antisemitism. On April 26, the office of the president of Columbia University issued a letter acknowledging “the antisemitism being expressed by some individuals,” going on to say, “Chants, signs, taunts, and social media posts from our own students that mock and threaten to ‘kill’ Jewish people are totally unacceptable, and Columbia students who are involved in such incidents will be held accountable.”

Some students have pushed back, arguing that most demonstrations are not antisemitic and that their views are being willfully mischaracterized by some politicians who are cherry-picking bad moments to justify a heavy-handed police response to peaceful protests about the Palestinian people.

It’s naïve to pretend that political manipulation is not a factor here, and much of this is also being filtered by the US presidential campaign. But it’s also naive to suggest that there’s not a disturbing element of dynamics like anti-semitism as well. But that’s not what protest creep is about.

As Jeremy Peters wrote in the New York Times, many student demonstrators are not only motivated by the events in Gaza, but have linked those to “policing, mistreatment of Indigenous people, discrimination toward Black Americans, and the impact of global warming.”

It’s not surprising to see acts of solidarity among groups, but is it helpful? What about when the protests veer into issues like Zionism itself? If the debate is now so wide that it includes asking if Israel has a right to exist as a Jewish state–and that is common–should there be debates around the right of Muslim countries, theocracies, or kingdoms to exist? Will there be debates about Jordan’s right to exist, a country carved out of the British mandate in 1946, two years before Israel was founded? What about countries like Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, or others whose lines were randomly drawn on a map by Western governments after the war?

These are interesting questions, but are they helpful for the current crisis? At best, they force an endless regression into debates about settlers and nationalism – questions that have no simple answers. At worst, they suggest a double standard of morality and accountability.

Canada, the US, and Australia, for example, all struggle to find answers to painful and real questions about Indigenous rights and land claims, but outside of some basic sense of solidarity, is blending these with the crisis in Gaza useful? Do these debates bring clarity, or is the chaos today being used opportunistically by some radical elements to amplify any cause?

Finally, who is responsible for protest creep? Part of it lies with the media for using loose terms to lump disparate groups together and blurring messages so nuanced distinctions get lost. Part of it lies with the protesters, who are caught in their own momentum and are losing control of the narrative. And lastly, part lies with the politicians and the authorities, who label groups and torque up fears to bolster their agendas. It’s a mess, and it looks like there is no way out.

No way out.

That’s always the problem with mission creep – and now with protest creep. There’s no exit strategy. The aims become so big, so endless, that the whole idea of a peaceful, practical solution is lost. The fight itself has become the whole point.