When Canadian Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson unveiled Canada’s critical minerals strategy last year, he emphasized the crucial link between building mines and reducing carbon emissions.

“It cannot take us 12 to 15 years to open a mine in this country,” he said. “Not if we want to achieve our climate goals.”

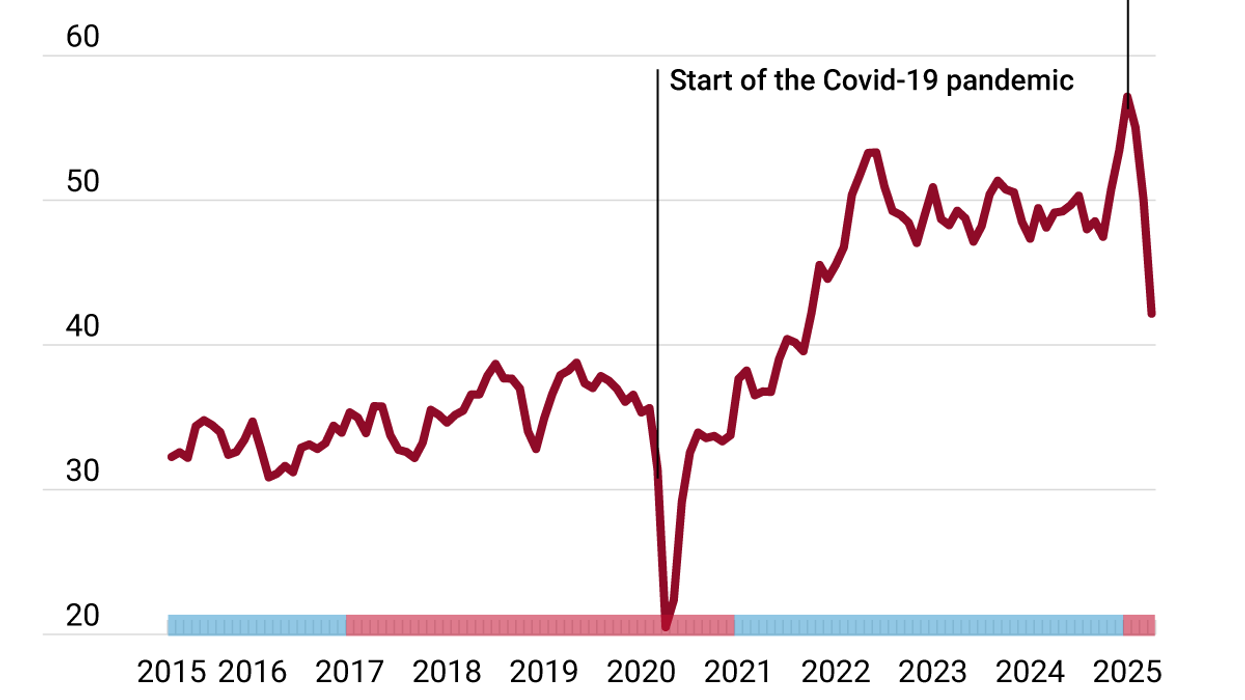

In fact, though, Wilkinson was understating the problem. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, the average turnaround time for opening a mine in Canada — from discovery to production — is nearly 18 years. Things are not that much faster in the United States, where the average is 13 years.

President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau are pushing hard for a green transition — a generational shift away from fossil fuels to cut the emissions that cause climate change. But their plans depend on lots of new mines, and in both countries, there are complex, unpredictable regulatory processes that stand between venture capitalists and ore production. Those processes are designed to protect the environment and Indigenous communities, but they are also standing in the way of the production of the key ingredients in batteries, electric vehicles, and clean-energy grids — copper, nickel, lithium, graphite, cobalt, and rare earth elements.

Where are the permits?

Biden and Trudeau have promised to tackle the problem, and both have taken steps to make it easier. But they don’t control all the levers, and there is little reason to hope that the lead-up times will be shortened quickly enough to allow for the ramp-up in production that experts say we need to allow both economies to shift away from fossil fuels.

The amount of minerals the world will require to make that shift is enormous. If the world is serious about reaching its climate goals — reaching carbon zero by 2050 — many vast mines will have to start producing billions of tons of copper, lithium, and other minerals from the ground — six times more production than is currently taking place. Green technology — solar panels, batteries, windmills — requires a lot more minerals than traditional energy technology. There is zero debate about the benefits of switching — no matter what politicians and fossil fuel lobbyists say about windmills killing birds — but there will have to be a lot of big holes dug in the ground. These holes will do significant damage to ecosystems, and communities will oppose them, threatening the transition.

Relying on a risky ring

Consider the “Ring of Fire,” a vast area of mineral deposits under the peat bogs of Northern Ontario. More than 26,000 claims have been staked in the ring-shaped area where volcanic deposits contain rich veins of platinum, palladium, copper, nickel, gold, cobalt, and chromite worth tens of billions of dollars – if it can be mined. But as the Wall Street Journal explained this week, that is no sure thing.

Indigenous communities are divided. Some want the development and opportunities that the mines could bring, while others are horrified by the prospect of a big new mining road going through, disrupting delicate northern ecosystems, and releasing large amounts of carbon locked in the peat.

In Canada, courts can kill projects if the proponents fail to consult sufficiently with Indigenous communities.

Proponents do not always do a good job on consultations, and it is also not always clear who has to be consulted. A gas pipeline in British Columbia ran into unexpected problems, for instance, when a judge ruled that hereditary chiefs, not just elected chiefs, have a legal right to be consulted about developments on their territory.

Also, Canada has committed to implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which is expected to give Indigenous opponents of projects new arguments to make in court.

“From a proponent’s perspective, when they look at Canada and want to invest in Canada, that is a huge risk,” says Heather Exner-Pirot, director of Natural Resources, Energy and Environment for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

“It's very uncertain,” says Exner-Pirot, “and proponents don’t like that.”

Cutting through the red tape is not an easy task

Canada has promised to unveil a plan this year to make the regulatory process smoother. Biden, meanwhile, has thrown his support behind efforts in the United States to reform permitting processes.

Beyond that, both countries are offering financial incentives, but regulatory processes have not gotten easier – and they may not.

“A lot of what the federal government does is fairly schizophrenic,” says Ian Lange, program director for Mineral and Energy Economics at the Colorado School of Mines. “Everyone has their own little fiefdom that they can affect. And so they might try. But, you know, the real changes have to come with legislative changes.”

When Biden visited Ottawa in March, he and Trudeau promised to take steps toward “reliable and sustainable critical mineral supply chains,” but it is not clear that either can deliver.

“We have a tightly divided Congress, and Canada has a minority government, that's a reflection of the same grumpy-electorate kind of vibe, where they're not really happy with where things are going,” says Christopher Sands, director of the Wilson Center's Canada Institute. “But that undermines the political capital on either side of Trudeau, who has been in office for a long time, and Biden, who I think has some struggles on his popularity front.”

But neither country can proceed with the transition away from fossil fuels without vastly bigger supplies of minerals, and that won’t happen unless investors decide to put their money down.

“Here's the thing about mines, they are very slow money,” says Exner-Pirot. “So you're putting up billions of dollars up front, before a single ounce of ore is ever taken out, and you get your money back. And now with interest rates, it's very expensive to wait 14 years of putting in money and the cost of capital on that before you get any kind of return on investment.”

“You're talking about millions and millions of dollars, so the timelines need to be shortened.”