“Pain and agony and suffering,” wrote Sam Angel, about his job hunt. He recently graduated with a masters in Cold War military history from Columbia University in New York, having decided to go right into a masters program after finishing undergrad. He thought it would up his chances of getting a job in military intelligence. But after landing an offer in the federal government, his position was cut due to the Trump administration's hiring freeze before his first day. He's spent months searching for another to no avail.

“Now I have two degrees. But it doesn't mean anything."

I had posted to Instagram asking recent graduates to share their experiences, and Sam’s experience echoed through dozens of replies: 32 others described months of applications, hundreds of resumes, endless networking – and no job offers.

“You would think with a Columbia degree and a Blackrock internship you’d be minted,” said James Kettle, who after applying to hundreds of jobs says he’s “losing hope that I am going to find white collar work.”

“Which sucks because I spent like, you know, 200,000 bucks on my college degree.”

Over the past two decades, tuition and fees at four-year colleges have climbed 141%, an average pace of 7% per year. The average student graduates with $39,075 in student loans.

Students were told that investment would pay off. For decades, a college degree was an economic launchpad and safety net in the United States: Graduates could generally expect to land work faster than their peers without a degree, and were more likely to be insulated from financial crises.

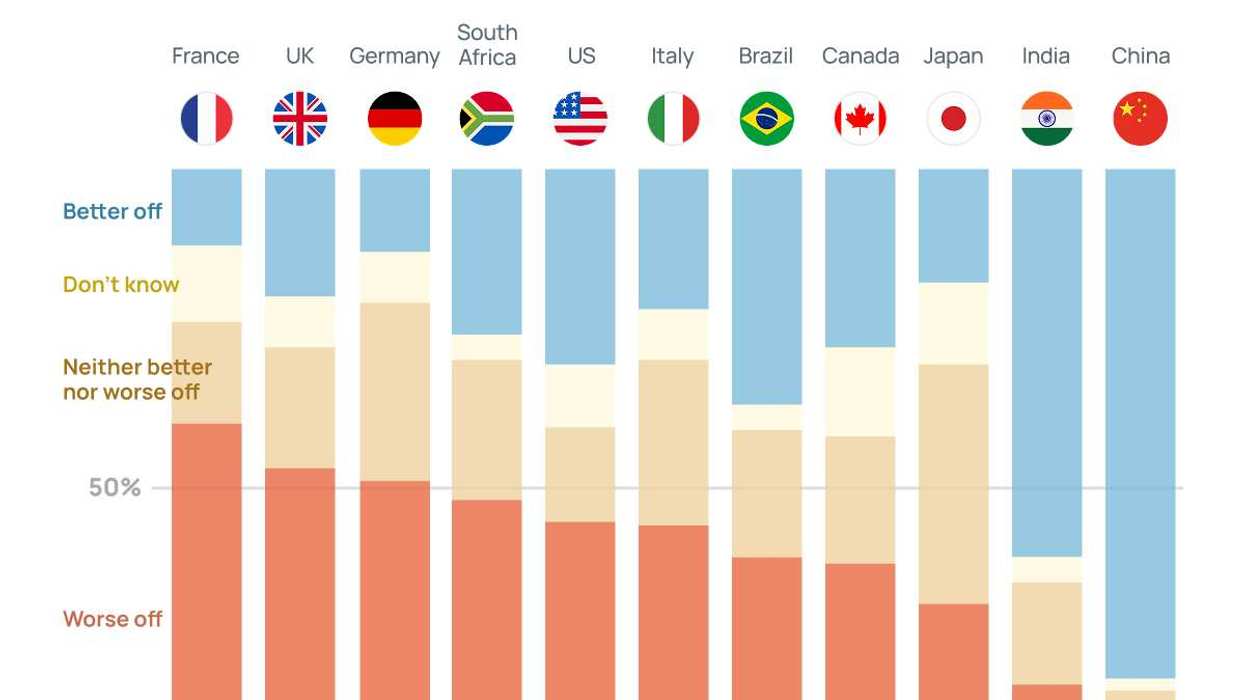

But that college premium has now vanished. Recent college graduates are struggling more than ever. Since late 2018, their unemployment rate has regularly exceeded the overall labor force. The national unemployment rate is roughly 4%, but among recent college graduates, it averaged 6.6% over the last year.

“It honestly feels like all the work I’ve put in over the years – school, internships, networking – hasn’t really gotten me anywhere,” says Paige Mazzola, a 22-year-old recent graduate from UC Santa Barbara.

Why is this happening? One explanation is that companies are hiring fewer people. Linkedin data shows that hiring is down in most industries. Gone are the days when staffing cuts meant financial trouble, and a high headcount was a sign a company was growing. Today, CEOs are flaunting leaner workforces as a point of pride, and ever-shrinking teams are being trumpeted as a sign that the firm is embracing artificial intelligence.

Another is that competition among new grads is tougher simply because there are more of them. College attendance has climbed steadily for decades, and the pandemic only swelled the ranks further: many students delayed graduation by taking gap years to avoid online classes, or stayed on for master’s degrees to make up for lost classroom time caused by the pandemic. I know this firsthand. I was supposed to graduate in 2022, but after taking time off during COVID, I ended up walking across the stage two years later – alongside many of my original classmates. The result is a crowded pool of job seekers, where the class of 2024 isn’t just competing with each other, but slightly older and more experienced bachelor and master’s degree holders.

As if that wasn’t enough, there are still more factors cutting against recent college grads. A big one: the American economy is transitioning to new industries that graduates weren’t told to prepare for. In 2018, the top three industries hiring new grads were tech, financial services, and marketing. That led many people to make the informed decision to study things like computer science, economics, or communications.

Yet in 2025, computer engineering is third on the list of majors least likely to get you a job. Meanwhile, Linkedin’s 2025 Grad Guide reported that the industries hiring the most new grads are construction, utilities, and oil, gas, and mining – not what many who entered college in hopes of a white-collar career path were likely to have been preparing for.

Men have it worse. Right now, healthcare is one of the US economy’s strongest growth engines. In 38 of 52 states, it’s the biggest employer — and women are the main beneficiaries. Of the 135,000 new jobs filled by female graduates last year, nearly 50,000 were in healthcare, more than twice the total gains for men across all fields. The surge is driven both by demographics — one in five Americans will be over 65 by 2030 — and by the simple fact that the US is, bluntly, an unhealthy nation.

In other words: fewer jobs, fiercer competition, and degrees that don’t line up with the work that’s actually out there. No surprise, then, that the college premium has flipped – grads are now more likely to be unemployed than everyone else.

And lurking just offstage? AI. Stay tuned for more on that and how high college graduate unemployment is reshaping politics in tomorrow’s newsletter.