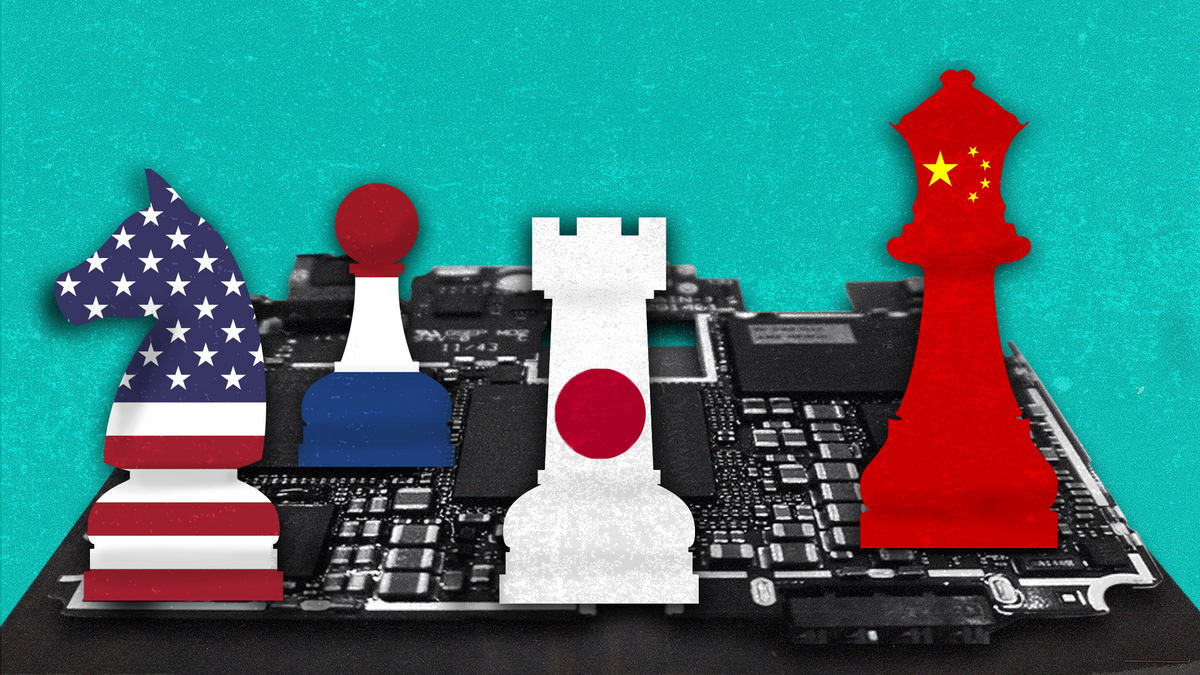

Japan and the Netherlands have reportedly agreed to join US export controls to stop China from getting the machines to make some of the world’s most advanced semiconductors — in part, the Biden administration claims, to make high-tech weapons. It's a major milestone in the broader US push to beat China in the race to dominate global tech with "weapons" such as the $52 billion CHIPS Act, which aims to subsidize domestic chipmaking in America and make it harder for China to access the tech.

We learn more from Eurasia Group's senior analyst Nick Reiners.

Why is this a big deal?

Until this point, the US was alone on the world stage in its campaign to deny China access to key technologies. It is quite a novel thing to take this approach to geopolitical competition. There are existing multilateral export control mechanisms like the Wassenaar Arrangement, but they don't really work anymore — not least because Russia is a member. So the US went out unilaterally and took all these measures.

The US has wanted to bring on key countries like Japan and the Netherlands before. But in the end, it decided to go it alone to prove it had skin in the game, and it wasn't clear that it would gain the buy-in from other key countries. Now, finally, Washington has two very important countries to sign on to its approach of denying China access to semiconductors used for artificial intelligence and other high-tech applications.

Why are the Dutch and Japanese so crucial to the US effort, and why are they coming on board?

In particular, the Netherlands has one company, ASML, that makes something called Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography machines, or EUV machines, which churn out the world's most advanced chips, as well as Deep Ultraviolet Lithography, which are less advanced than EUV machines but still extremely complex. Japan also has important chipmaking firms, including Tokyo Electron and Nikon.

Fundamentally, the governments of the two countries agree with the principles underlying America's actions and that China is a security threat. They agree that China is a geopolitical adversary and that it's worthwhile to try to reduce its access to high tech.

At the same time, the US can threaten Japan and the Netherlands because the global chip supply chain is so complex and integrated that pretty much any product relies in some way on US technology. So, the US has the ability to deny ASML or Tokyo Electron access to key components that are required to build these machines in the first place. Under the Trump administration, the message was: If you don't sign here on the dotted line, then we might be forced to take more aggressive measures. But it’s unlikely that Biden administration officials have made an explicit threat like that.

Does this have anything to do with the CHIPS Act passed last year by the Biden administration?

There is certainly a link. The legislation contains what's called guardrails, meaning that if companies get US subsidies, they're not allowed to invest in certain types of projects in China. The overall objective is similar to ensuring that investments in the semiconductor sector are made within the US and allied countries — and certainly not in China. That's part of this broader "friend-shoring" trend that we hear a lot about.

What's all the fuss about EUV machines?

Chips are cut out of silicon wafers, big circles made of silicon. What lithography machines do is, in simple terms, use light to cut microscopic grooves in the wafers. The tech allows you to print these unbelievably tiny patterns to make circuits. The smaller the grooves, the more transistors you can cram onto each chip, and the more powerful the chip becomes. EUV machines are a piece of the most advanced tech in human existence, a triumph of human engineering. And only one company in the world makes them: ASML.

Didn’t the Dutch government ban exporting EUV machines to China in 2019?

Yes, but it's impossible to know whether the Chinese have gotten hold of one, even if they're they're not supposed to. ASML has not sold them any, but there is no doubt that China is seeking access to these machines through other means.

And can't China build its own EUV machines?

That would be an immensely complex engineering feat that requires thousands of components and human capital from all over the world. It took 20 years for ASML to build EUV machines. China will certainly try, but it'll likely take them 10 years or more — if they ever achieve it at all.

It sounds as hard as building a nuclear bomb …

I'd say it would be even harder, based on the sheer complexity and the number of components and how perfect everything has to be for it to work correctly.

Even if China is not allowed to have EUV machines anyway, Japan and the Netherlands joining US export controls still hurts Beijing. But how?

This is part of a broader strategy to make life as difficult as possible for the Chinese tech sector and to make the technological gap between the US and China as wide as possible. And because China is heavily dependent on semiconductor imports, the West in general — and the US in particular — has a point of leverage that it can exert on China very asymmetrically.

That said, I'm dubious about the US claim that China might use these semiconductors in their weapons because, for instance, Beijing doesn't need the latest chips to make most of its missiles. It can easily get hold of enough of these chips one way or another, even if it doesn’t produce them all domestically.

If it's not really about weapons, then why does America want to stop China from getting its hands on these state-of-the-art chips?

The US and China are in a race to develop the most powerful AI applications and the most powerful high-performance computers, which themselves can be used for military purposes — for example, designing advanced weapon systems. And for that, you need vast quantities of chips, so what the US and its allies are doing delays China.

Moreover, the US increasingly sees less and less of a distinction between China's military and civilian economies. This week, the Biden administration reportedly banned pretty much all US companies from selling any US-made tech to Huawei, which Washington sees as an agent of Beijing. Crippling Huawei's civilian business is a way to hurt China because the company also works for the military.

How might China respond?

In general, they haven't tended to respond in a symmetrical way. To a certain degree, the export controls are kind of convenient to Xi Jinping because they reinforce the need for China to become self-sufficient. China is also trying to present itself around the world as being a more responsible global stakeholder compared to the US by not weaponizing interdependencies and so on, which is, of course, very dubious. But that's their public-facing rhetoric.

China can retaliate in other ways that maybe aren't directly linked. For example, they could stop cooperating with the US on things like climate change. They could downgrade diplomatic relations in other ways, and they can also make life difficult for US companies and Western companies by not approving corporate mergers. Or they can encourage Chinese consumers not to buy Western goods. That might sound kind of soft and nudging, but the effects can still be very damaging to Western companies trying to do business in China.

Would any other countries sign up, too? Perhaps South Korea?

Right now, South Korea is the other big one because it has Samsung, but the South Koreans are also a bit of a special case because they are much more exposed to China and its companies, as well as the North Korean issue. South Korea is just generally more vulnerable to China and Chinese pressure. That's partly why the so-called Chip4 Alliance — which was supposed to include the US, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea — hasn’t yet really gotten off the ground. I wouldn't bet on South Korea joining anytime soon.